Introductions to our Group theatre visits

Group Visit:

Monday 02/03/26

7.30pm performance

at the Donmar Warehouse

REMEMBER TO BRING YOUR TICKET

& CHECK COACH TIMES

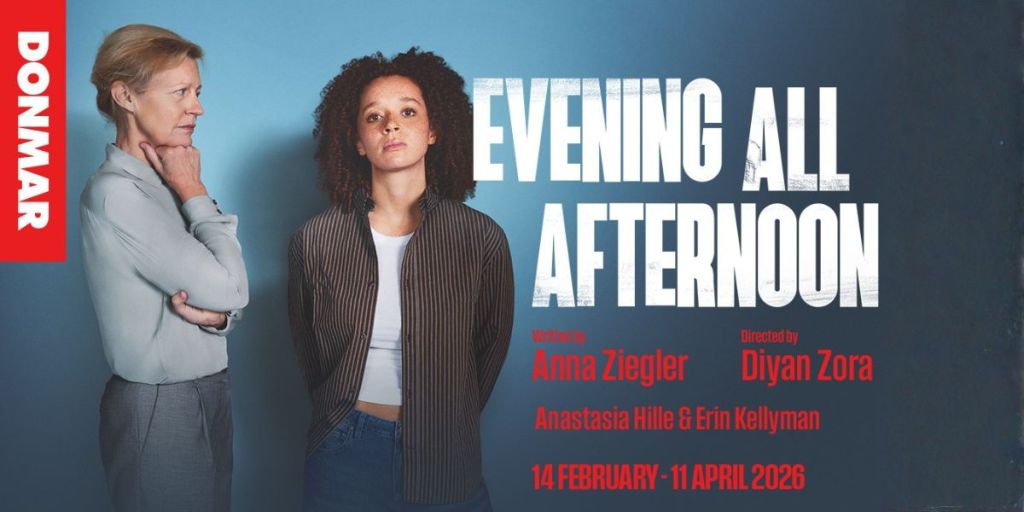

Fredo writes – EVENING ALL AFTERNOON with Anastasia Hille and Erin Kellyman

I don’t know much about Anna Ziegler, the American playwright who won the What’sOnStage Best Play Award for Photograph 51 in 2016. That play had a successful run in the West End with Nicole Kidman in the leading role. Evening All Afternoon is a world premiere, and there has been strangely little publicity (or did I just miss it?). However, it’s had very good reviews, and one of my spies at the theatre has advised me to bring tissues.

The play begins at 7:30 and there is no interval. It ends at approx 9.00pm.

The review from WhatsOnStage is at this LINK.

Group Visit:

Monday 9/02/26

7.30pm performance

at the Aldwych Theatre

REMEMBER TO BRING YOUR TICKET

& CHECK COACH TIMES – WE SHALL NOT BE ATTENDING THIS PERFORMANCE

Fredo writes – SHADOWLANDS

He was Jack to his friends, and an enigma to everyone else. Clive Staples Lewis was born in Belfast in 1898, the grandson of a Church of Ireland priest, and the great-grandson of a bishop. Following the death of his mother in 1908, he was sent to boarding-school in England, where he suffered from culture-shock, and was very unhappy.

At this point he lost his Christian faith and became an atheist, yet when he returned to Oxford after serving in the First World War, he found his faith again and became an eminent Anglican theologian. During the Second World War, he broadcast on religious programmes for the BBC.

Later in life, he accepted the newly-created chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge. Although medieval literature was his field of expertise, he is best remembered for his Narnia books for children. One of these, The Magician’s Nephew, is currently being filmed by Greta Gerwig, the director of Barbie. Among his books for adults, A Grief Observed is a raw account of his own experience of bereavement, and is still a standard work recommended by bereavement counsellors.

Jack seemed to be a confirmed bachelor, drinking in the pub with his friends David Cecil and JRR Tolkien and other dons (they styled themselves “The Inklings”) and yet he appears to have had a long and probably non-platonic relationship with the mother of a comrade in arms. She was 26 years older than him, but they lived together until she was hospitalised in the late 1940s. After that, he visited her every day until her death. All in all, Jack Lewis seems an unlikely hero of a play.

His life took an unexpected turn when he started a correspondence with the American poet and novelist Joy Davidman. Joy’s life in some ways reflected Jack’s own. A child prodigy, she was Jewish, but rejected her birthright faith at an early age, She lived through the Depresssion, and witnessed the horrifying spectacle of an orphan child throwing himself to death because of hunger. Convinced that Capitalism didn’t work, she joined the American Communist Party. Her early academic success was followed by marriage to David Gresham, who wrote the strange novel Nightmare Alley (filmed with Tyrone Power in 1947, and again with Bradley Cooper in 2021). They both discovered their faith in God, and became Christians. Nevertheless, the marriage was a demoralising experience for Joy: Gresham was an abusive alcoholic. She divorced him and took her two sons to England.

She then formed an intense friendship with Jack. They were intellectually compatible and shared religious beliefs. Joy assisted him on his memoir of his conversion, entitled, coincidentally, Surprised by Joy, which he was working on before he met her. In order to assist her to continue living in England, Jack married Joy in a civil ceremony. It was a marriage of convenience; they didn’t need to live together and they didn’t.

But life had a few surprises and shocks in store for Joy and Jack. In Shadowlands the playwright William Nicholson explores the discovery of love between Joy and Jack, and how this love and their faith is tested by the events in their lives. It’s an emotional play. Take your handkerchiefs.

Joy and Jack

William Nicholson

Group Visit:

Wednesday 28/01/26

7.30pm performance

at the

Duke of York’s Theatre

REMEMBER TO BRING YOUR TICKET & CHECK COACH TIMES

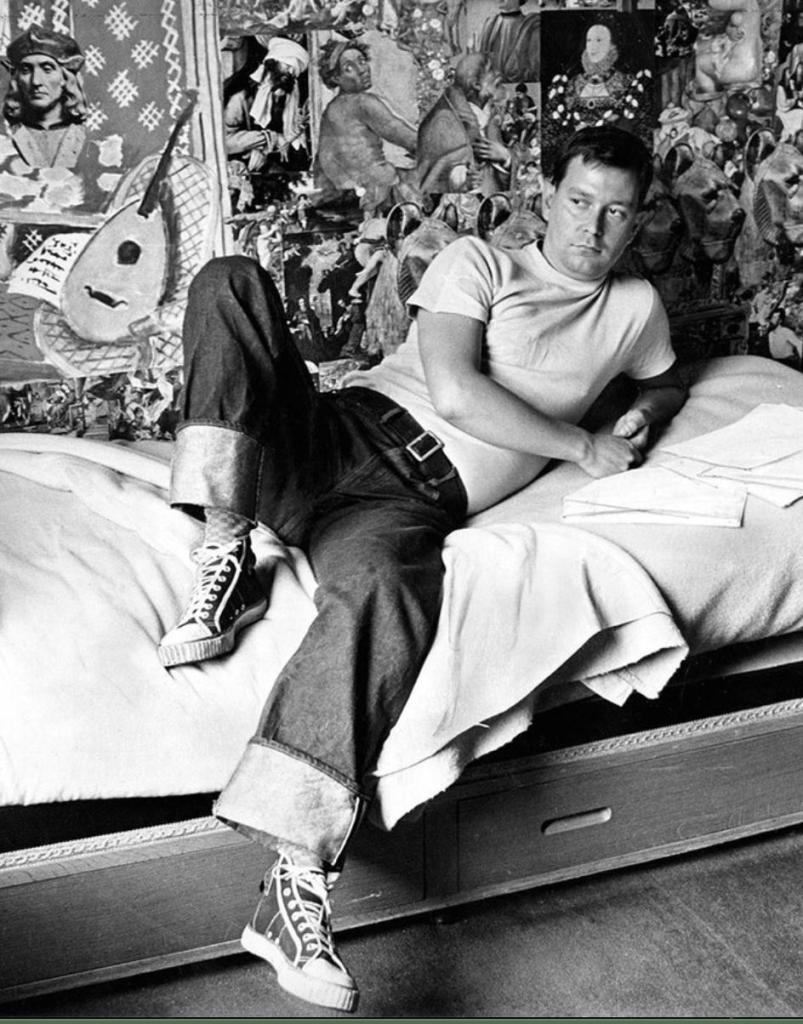

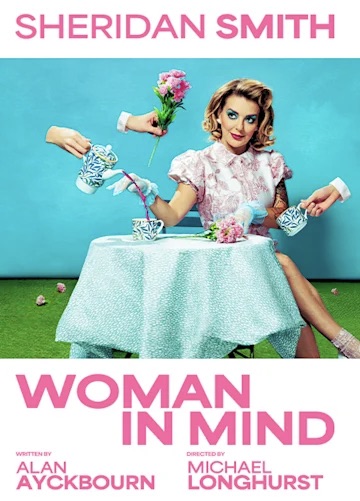

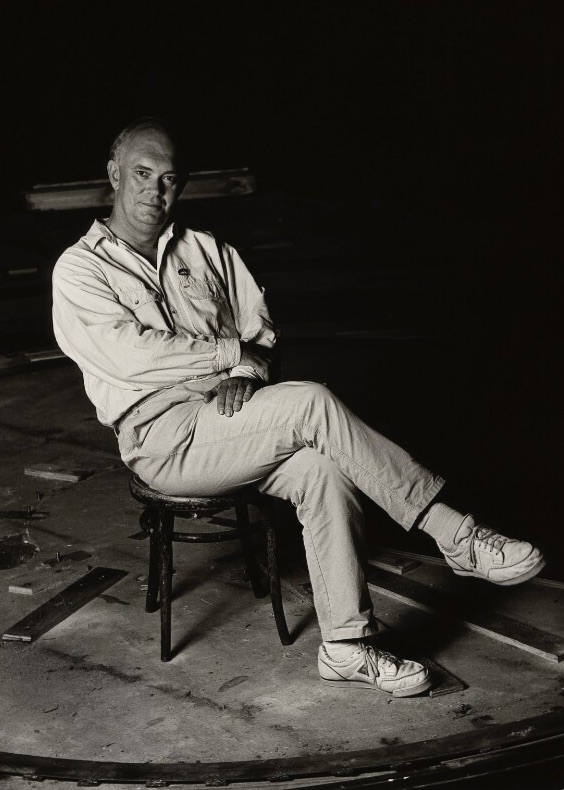

Alan Ayckbourn

in the 1980s >

Fredo writes – WOMAN IN MIND

While the West End theatre in the 60s was overshadowed by Angry Young Men (John Osborne) and Angry Intellectuals (Harold Pinter) or just mere Intellectuals (Tom Stoppard), audiences welcomed light relief in the comedies of Alan Ayckbourn.

This actor-turned-playwright had a seemingly endless fund of plays produced at his home theatre, the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough. As an actor, he knew a thing or two about getting an audience to react; as a writer, he had an ear for revealing dialogue, and a few tricks up his sleeve to amuse and titillate. How the Other Half Loves (1969) had two different households on the same set, and inevitably their dialogue hilariously overlaps. Bedroom Farce (1975) presents four couple in four bedrooms on stage at the same time, while the trilogy The Norman Conquests (1973) presents the same narrative in three plays, in three different rooms, happening on the same afternoon, exiting one play and entering another. They were fun, and the technicals innovations were ingenious.

With Woman in Mind (1986), Ayckbourn turned to a more serious theme. He started writing the play with a male protagonist, but feared that critics would draw parallels with his own life. He then realised that a female voice might engender more sympathy from the audience, and the main character became Susan, a vicar’s wife on the verge of a breakdown.

The tone of this play is darker than usual and, for the first time, Ayckbourn reveals the action through the eyes of one character, rather than allowing us an overview of the carryings-on. This envelopes us in Susan’s world – or should that be “worlds” as she has a fantasy life, as well as a harsher reality?

In this new production, director Michael Longhurst (previously Artistic Director of the Donmar) uses a daring device at the start of the play. The first 40 minutes are performed before a ‘safety curtain’, challenging us to decide which side of the curtain is the safest area for Susan, in real life or in her head. It will be interesting to see how the usually sunny Sheridan Smith interprets this role.

Although I was once a fervent adherent of Alan Ayckbourn, I found that his later plays didn’t quite work for me. The astringent strain of misanthropy seemed to grow into unpleasantness, and as his earlier plays were revived, they looked facile and too dependent on gimmickry. His most recent play, last year, was his 91st.

The time has come for reassessment, and Woman in Mind is a good place to start. Be prepared for an evening that is not a riotous comedy. I’ll approach it with an open mind. You should, too.

Group Visit:

Sunday 25/01/26

3.30pm Matinee performance

at The Other Palace theatre, Victoria

The Theatre is situated at

12 Palace St, London SW1E 5JA, just off Buckingham Palace Road, and is behind the Victoria Palace Theatre. It is a 5 – 8 minute walk from Victoria Station and can be approached through Cardinal Place shopping mall.

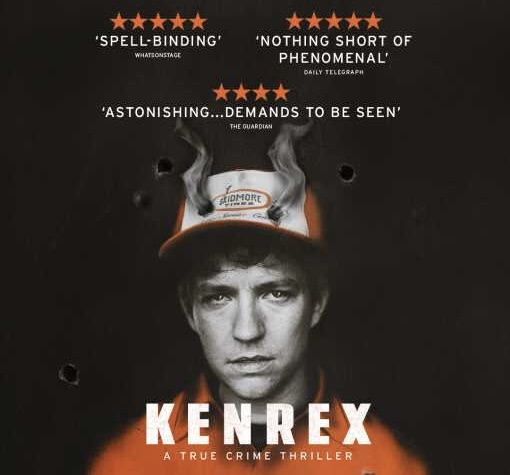

Mike writes – KENREX

We loved this show but don’t want to give too many details away in advance. You can read my review at this LINK.

Play the trailer before you venture into the woods – Click on this LINK

Fredo writes – INTO THE WOODS

There are good reasons why Into the Woods is one of Stephen Sondheim’s most popular shows, frequently performed in American schools and colleges. It starts, as all the best stories do, with “Once upon a time…” The cast includes Cinderella; her father, stepmother and stepsisters; Little Red Ridinghood; Jack of Beanstalk fame; a Baker and his Wife; and importantly a Witch. They all go into the woods, encounter a Wolf and, as a bonus, Rapunzel and not one but two Princes. Do they have adventures, and is it scary? Yes, it is! Is goodness rewarded? What do you think? And does it end happily ever after?

Of course it does! But wait a minute – that’s just the Junior Version, and only Act One of the longer, more complex show. I don’t know what details have been air-brushed out of the original for that version, but I suspect some of the more uncomfortable details may be glossed over for younger audiences. Here at the Bridge we have the full Two Act version going into darker territory.

Of course it does! But wait a minute – that’s just the Junior Version, and only Act One of the longer, more complex show. I don’t know what details have been air-brushed out of the original for that version, but I suspect some of the more uncomfortable details may be glossed over for younger audiences. Here at the Bridge we have the full Two Act version going into darker territory.

Let’s start by saying that Into the Woods is indeed a very entertaining show. The mere idea of taking characters from familiar stories and setting them on individual quests is genius, but Sondheim and librettist James Lapine go beyond that, to resolve all the confusions…and then the conflicts that arise.

They set the scene where all the characters reveal their hearts’ desires to us: Cinderella wants to go to the Festival and dance before the Prince; and Red Ridinghood wants to visit Granny in the woods with a basket full of bread and sweets. Jack’s mother needs Jack to sell his cow Milky White, but he really wants to keep her as his best friend. The Baker and his Wife desperately want a child, but first have to break the spell that the Witch once cast on their house. Each has a wish, and Sondheim sends them off into the woods with a jaunty, skippety-hop rhythm to get what they want.

There’s a note of caution: the Ghost of Cinderella’s mother challenges her:

“Do you know what you want?

Are you certain what you wish is what you want?”

There’s a tension here: they know what they wish for, but where will that lead them? The Narrator tells us that these are not sophisticated people. They make choices, but they don’t consider the consequences.

(Gracie McGonigal)

At this point, it may seem that the message of Into the Woods is simply to be careful what we wish for. And indeed, that is part of it. It’s fun to watch them pursue their goals, but the Witch gives them only three midnights to complete their tasks, and they become more ruthless as time passes.

At the outset, they tell us that they are going

“Into the woods

To get the thing

That makes it worth the journeying

To get my wish

I don’t care how…“

Even the Baker helps his Wife to buy Jack’s cow Milky White for only 5 beans. It’s clear in her mind

“If you know / What you want

Then you go / And you find it / And you get it.

There are rights and wrongs and in-betweens

No one waits / When fortune intervenes.

Everyone tells tiny lies –

What’s important, really, is the size.

If the end is right / It justifies / The beans.

There are moral compromises being made here, which seem to make the Baker uneasy. Meanwhile, Cinderella seems disappointed in the first two balls that she attends, and is unimpressed by the Prince. As the third midnight approaches, she changes her mind; perhaps her wish to just dance before the prince has been elevated to another level – she now wants more.

The younger folk have changed as well. Red Ridinghood has strayed from the path and encountered the Wolf. He has carnal desires (he wants to eat her) but afterwards, she realises that the experience has changed her. She knows things now that she didn’t know before, significantly that Nice is different than Good.

Jack has climbed the beanstalk, seen riches and stolen the hen that lays the golden egg from the Giant’s kingdom. Then he has gone back again to steal the harp. As he climbs back down to earth, it dawns on him that things are “different than before.” Like Red Ridinghood, he’s lost a certain amount of innocence, but then that’s part of growing up.

Have they got what they want? Is it happily ever after? Well, yes – but: “to be continued” says the Narrator! This is just the Interval.

(Jo Foster)

Act Two reveals that there are indeed consequences to their previous actions. Each one sought out what they wanted single-mindedly, and without regard for each other. They even ignored Jack’s Mother’s plea to help her get rid of the dead Giant in her garden. They ignored the second beanstalk shooting off from the bean that one of them (which one?) carelessly discarded. In order to escape a new threat, they have to go into the woods once again.

This time the woods are less magical. It’s a place where they have to confront their fallibility, based on what they’d been told in the past. Cinderella had already questioned –

“Mother said be good,

Father said be nice…

What’s the good of being good?”

Red Ridinghood had disregarded the advice that she was given –

“Mother said

Straight ahead’

Not to delay or be mislead….”

What’s the point of being good, if nice is – well, nicer? And the influence of parents isn’t always for the better. The Witch blames the Baker’s parents for the curse she placed on them, but she herself has a strange approach to mothering her adopted daughter, Rapunzel. This is based on her fear of the outside world, which she considers in her great lament, Stay With Me.

“Who out there can love you more than I?” she asks, but later has to recognise

“Children can only grow

From something you love

To something you lose.”

The contrast between being nice and being good is held up for scrutiny throughout the show. While the characters believe themselves to be good, the Witch excoriates them as she exposes their shortcomings:

“You’re not good, / You’re not bad, / You’re just nice.

I’m not good, / I’m not bad, / I’m just right.”

(Kate Fleetwood)

The result is disarray, resentments rise to the surface, and each one blames the other for what’s gone wrong. Try to keep up as they hurl blame at each other in Your Fault . Each one tries to wriggle out of their responsibility. Can they be redeemed?

Redemption comes when they realise that selfishly looking out for themselves doesn’t work: they need to work together to defeat the dangers that surround them. The Baker is overwhelmed. He runs away, but finds his long-lost father, who shows him what running away can lead to. He returns and joins forces with Cinderella, Red Ridinghood and Jack.

Redemption comes when they realise that selfishly looking out for themselves doesn’t work: they need to work together to defeat the dangers that surround them. The Baker is overwhelmed. He runs away, but finds his long-lost father, who shows him what running away can lead to. He returns and joins forces with Cinderella, Red Ridinghood and Jack.

There are deaths in the second act which the characters have to face up to. Cinderella has to introduce her younger friends to the responsibilities of growing up. We recall that both she and Red Ridinghood had advice from their mothers, and that Jack’s mother fretted about him. However, Cinderella tells them:

“Mother isn’t here now,

Nothing’s quite so clear now –

Who can say what’s true?”

The time has come for them to make their own decisions, and Cinderella and the Baker warn them “People make mistakes.” Still, they add, even when others are not on their side “No-one is alone.”

(Jamie Parker)

Is this a comfortable, reassuring Broadway ending? I don’t think so. The Witch had complained earlier that children don’t listen. Now she cautions that children will listen, the mistakes of parents will be visited on their offspring. We must make our own decisions, but there must be regard for others. We all have to confront life’s uncertainties, but we need to overcome them too – we have to go into the woods again and again to explore our known or hidden desires, our fears and gratifications. Just like the characters in the show.

And by the end, have they learned anything? Have we? The final words are “I WISH.”

Group Visits:

INDIAN INK

Mon 12 January

at Hampstead Theatre

7.30pm performance

&

ARCADIA

Wed 18 February

at the Old Vic

2.30pm MAT performance

Fredo writes – INDIAN INK and ARCADIA

For a period in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, audiences were in awe of the playwrights Harold Pinter and Tom Stoppard. Their styles were very different: Pinter, terse and elliptical, Stoppard expansive and allusive. It seemed that we had to worship at their altars on bended knee. I recall evenings that began with uneasy laughter at the first Pinter pauses and the nervous titters at the conceits in Stoppard’s word-play. And at the end, there were proclamations that we’d witnessed works of genius. We hadn’t always.

The demystification of Pinter started in 1994, with a revival of The Birthday Party at the National Theatre. This was directed by Sam Mendes, and in a stroke of casting genius, Dora Bryan played the bewildered Meg, who, like the play’s first audiences, had no idea what was going on.

However, Pinter started to indulge his publicity, and his later works contain an unwelcome serving of wilful obfuscation. I recall squirming as an actress in Moonlight gnomically intoned, “I’m going to make an omelette.”

Stoppard was the more consistent dramatist, and even at his most formidably intellectual, he kept an eye on entertaining his audience. Attention was paid to his breakthrough play, Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, centred on itheir relationship to Hamlet, and somehow ignored the major theme of trying to make sense of the world we find ourselves living in. I had a Damascene moment of understanding at the performance of this play at the Old Vic. A mother with two young daughters were sitting behind me, and I braced myself for an afternoon of two bored children becoming increasingly restless and distracting me. Instead, the girls – no doubt drawn by the casting of Daniel Radcliffe – were ahead of the rest of the audience throughout the play. They anticipated the funny situations and laughed at the comic lives, and their mother told me at the end that they had loved it. And I’d thought it was for intellectual adults only. To understand the play, you have to have a sense of humour.

It has to be said that Stoppard didn’t always achieve this level of accessibility. I’ve known audiences to struggle with Jumpers and Hapgood, and I’m in that number: there are good reasons why these plays are seldom revived. When he’s good, as in Travesties and The Real Thing, he’s brilliant. When he’s bad, he’s tedious.

Several of his plays – Night and Day, Undiscovered Country – are missing in action. This could have been said of Indian Ink, but Hampstead Theatre has been doing a thorough job (with varying degrees of success) at working its way through the canon of his work.

Indian Ink had a successful run at the Aldwych Theatre in 1995, with Felicity Kendall in the leading role of Flora, a young English poet who travels to India in 1930. This is the period of Gandhi’s first non-violent protests, a satygraha. With 70 followers , he stared the famous Salt March, to draw attention to taxes imposed by the British Salt Monopoly Act of 1832, The numbers on the march swelled, and it ended in violence, with the colonial police beating the protesters at Dharasana.

Flora is drawn into the world of Indian culture by her friend (or is he more than that?) Nirad. He explains the theory of nine rasas, which unite all forms of art in colour, mood and musical scale. The dominant one for Flora and Nirad is shringara, associated with the distinctive blue-black of Indian ink: it is the rasa of erotic love.

The play occupies two time frames. Flora’s story is set in the 1930s, but it is interleaved with that of her younger sister Eleanor, at home in England 50 years later. The elderly Eleanor is sought out by an academic researching Flora’s life. Eleanor’s reluctant revelations may not be the complete story. We see what happened, what may have happened, and how modern interpretation can distort the past.

This is a theme that Stoppard had explored two years earlier in his most celebrated play, Arcadia. Although this play appears to be packed with tangental discussions on physics, chemistry, thermo-dynamics and anything else the polymath writer can cram in, it is essentially a comedy of misunderstanding and misinterpretation. Concentrate on the central relationships of Thomasina and her tutor Septimus in the 19th century, and Hannah and Bernard more than a hundred years later. In each case, certainty is undermined by uncertainty, order by disorder. All Stoppard’s learning playfully spills into this argument, but don’t let yourself get bogged down by over-analysis. Sit back and enjoy it.

By happy coincidence, we are seeing these two plays a month apart. Thirty years on from her original performance as Flora in Indian Ink, Felicity Kendall, Stoppard’s sometime muse, returns to play Eleanor. This production has been so successful that Hampstead has extended the season due to audience demand

We then see Arcadia at the Old Vic, in a new staging, with a cast that includes Fiona Button, and the rising star Seamus Dillane.

Both plays were programmed before the death of Tom Stoppard last year, and it’s a fitting tribute to his talent that his work lives on. I’m an unapologetic admirer of his work. Even when he’s dull, he’s the most interesting person in the room. At his best, there are fireworks.

My favourite memory of him is not at one of his own plays. Mike and I attended Oklahoma! at the National, with Hugh Jackman in the lead. Two of our friends were sitting across the aisle, slightly behind us. When the big, energetic and epic dance number, Kansas City, ended, I glanced round to see if our friends had enjoyed it as much as I had. Sitting behind them was Sir Tom, with tears of pure joy streaming down his face as he rapturously applauded the dancers. A true man of the theatre.

Group Visit:

Wednesday 7/01/26

7.30pm performance

at the

Queen Elizabeth Hall

on the South Bank

TOP HAT

It broke records at Radio City Music hall in New York, and was the second highest-grossing film of 1935. And no wonder: with Art Deco sets, filmed in sparkling black and white, fabulous gowns, a cast drawn from the stable of Hollywod’s most reliable comic supporting actors, and a score by tune-master Irving Berlin, Top Hat transported audiences out of the Depression into a world of glamour and romance. Oh, and don’t forget the nimble tread of the feet of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, who would remind us that she did everything that he did, only backwards and in high heels.

This was the fourth outing of Astaire and Rogers as a team. The studio RKO had featured them as a speciality act with top-billed Dolores del Rio and Gene Raymond in Flying Down to Rio, and had been surprised by their on-screen chemistry. Two other films, Roberta and The Gay Divorce, followed quickly, but Top Hat was the most expensive to date.

Initially, Astaire wasn’t happy with the script, as he thought it too similar to Gay Divorce, and in truth, it does follow a formula: boy meets girl, she doesn’t like him, he seduces her through dance, there’s a misunderstanding, they reconcile by dancing together – but no, they don’t kiss. A little tinkering with the screenplay and a score by his new friend Irving Berlin, convinced Astaire to go ahead.

He was 36 and a late arrival in Hollywood. As a child, he’d resisted attending the same dance classes as his sister Adele, but started copying her moves. She was the more natural dancer, but he was the rigorous perfectionist. By the 20s they became a successful dance partnership on Broadway and in London, in shows such as Lady, Be Good and Funny Face, playing brother and sister roles. He became known for his dapper style. Adele later revealed he was often given a top hat to make him look taller.

The partnership broke up when Adele married the second son of the Duke of Devonshire, and was resistant to efforts to lure her back to the stage. Fred attended the Guildhall School of Music with his friend Noel Coward, to learn to play the piano. He made his way to Hollywood, where the report on his screen-test read discouragingly “Can’t sing. Can’t act. Balding. Can dance a little.” Fortunately producer David O Selznick detected his natural charm, and took a chance on him.

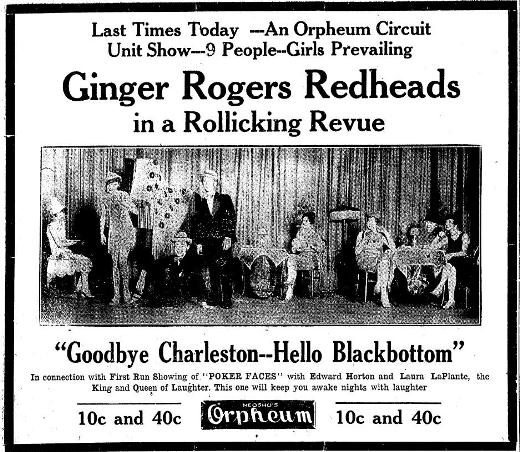

Meanwhile, the early years of Virginia McMath (called Ginger by her friends) sound like Act One of Gypsy. Her parents separated when she was a child, and her father kidnapped her twice. After the divorce, her mother, the formidable Lela McMath, left her with her grandparents while she went to Hollywood to sell a story she’d written. She became a successful screen-writer, re-married, and daughter Ginger took her step-father’s surname, Rogers.

When she was 14, she won a Charleston competition, and was taken up by the Orpheum Circuit for a 6-month tour as Ginger Rogers and the Redheads. After this, she headed for New York, and created a sensation in George Gershwin’s Girl Crazy. Also making her Broadway debut in that show was young Ethel Merman, and the pit band included Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman, Jimmy Dorsey and Glenn Miller. (This show was later rewritten as Crazy for You.)

Hollywood stardom didn’t follow automatically. Her first films were unremarkable, but she started to make an impression as a wise-cracking chorus girl in 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933. But it was all about to change.

At first, Astaire wasn’t impressed with his new partner. He later recounted, “Ginger had never danced with a partner before Flying Down to Rio. She faked it an awful lot She couldn’t tap and she couldn’t do this or that…but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got that so that everyone else who danced with me looked wrong.” Later he was more generous in his assessment, and attributed their success to her. He added that he had been demanding of all his dance-partners, to the point where they all cried – but Ginger never did.

She had two distinct advantages. She proved to be a hard working dancer with great stamina, and could act during the dance numbers. In addition, she had a flexible spine, just like sister Adele, and could make the low backwards bends look natural and graceful. On screen, they looked great together “He gives her class,” commented Katharine Hepburn, “and she gives him sex (appeal.)”

The third person in the relationship was choreographer Hermes Pan. This son of Greek immigrants had also had a hard-knock life. His father died when he was 11, and his uncle held the family at gunpoint because he wasn’t mentioned in the will. He took their money and burned it; if he couldn’t have it, no-one else could.

Young Hermes studied dance, and by the time he was 19 was on stage with the Marx Brothers in Animal Crackers. He met Rogers on the show Top Speed, but didn’t get together with Astaire until they met on the set of Flying Down to Rio.

They went on to work together on 17 of Astaire’s musical films (Pan choreographed 89 movies in total). Similar in height to both Astaire and Rogers, he often stood in as rehearsal partner, especially for Rogers, as her acting commitments often meant that she wasn’t available to work out the dances in their early stages.

Together Astaire and Pan created a new way of filming dance. They insisted that the dancer was always shown in full-shot – no cut-aways to close-ups props between the dancer and the camera. There had to be a minimum of editing, and the dancers were followed by the camera with tracking-shots. It’s simple, clean and demanding on the performers

The ace up their sleeve was Irving Berlin, who had been steadily turning out hit songs for many years. Berlin was born in Russia in 1888, and came to New York with his parents when he was 5 years old. With no formal musical training, he earned a living as a singing waiter and song plugger in the music business, singing in music shops to promote new material. Although he couldn’t read or write music, he started composing himself. Hit songs such as Alexander’s Ragtime Band, I Love a Piano and When That Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for Alabam followed, while commissions for the Ziegfeld Follies produced A Pretty Girl is like a Melody.

Berlin composed on a special piano set in the key of F sharp, with a lever to transpose it to F natural. He depended on an orchestrator to arrange his melodies, which seemed to pour so easily from him. Let’s not overlook his facility as a lyricist. The words of the song fall naturally from the singer’s lips.

They can be warm and heartfelt –

I’ll be loving you, always.

With a love that’s true, always

or wistful –

I’m dreaming of a white Christmas

or exuberant –

There’s no business like show business

They always sound like conversation, however complex the emotion or the music.

Berlin’s life wasn’t unmarked by tragedy. He married Dorothy Goetz when he was 24, but she died 6 months later, having contracted typhus on their honeymoon in Havana. His songs When I Lost You and What’ll I Do? express his grief.

In 1924, he fell in love with the heiress Ellin Mackay, but her father opposed the relationship because Berlin was Jewish, He disinherited his daughter when she eloped with Berlin, and her new husband quickly signed over to her the royalties of the song he wrote for her, Always.

Although he went on to write hit shows such as Annie, Get Your Gun and Call Me Madam, in 1934 Berlin was having a crisis of confidence. Astaire hadn’t met him before, but he encouraged his new friend to write songs for the new movie. Berlin submitted 13 songs, of which 8 were selected. With a new rush of self-esteem, Berlin then asked for 10% of the movie’s profits, if it earned in excess of $1.25 million. He became a very rich man.

The number Cheek to Cheek caused a serious dispute between the stars. Miss Rogers decided to design her own gown, and though Astaire liked to approve the costumes in advance, he didn’t see it until the day of the shoot. He was furious. The dress was smothered in ostrich feathers which shed tendrils at every twist and turn.

He lost his temper, but Rogers was adamant. A team of seamstresses was employed to anchor the feathers in place overnight, and the dance was committed to film the following day. Later, Astaire and Pan gave Ginger a gold feather to add to her charm bracelet. However, during this number in the movie, you can still see wisps of ostrich feather fall to the polished floor.

But they didn’t kiss. Well, only once , in the movie Carefree. In fact, this may be the only time Fred kissed his leading lady on screen. He didn’t need to; dancing with Fred Astaire was the greatest romance of any dancer’s life.

I think that to date the only one of the Astaire/Rogers movies that has made the transition from screen to stage is Top Hat. I suspect this is because television star Tom Chambers won tv’s Strictly Come Dancing with a lively recreation of the the title number, and the producers wanted to cash in on his temporary peak in popularity. Summer Strallen stepped into the Ginger Rogers role, and it was a popular success back in 2012 winning the Olivier Award for Best New Musical.

This new production was well-received at Chichester last year, and I’m already putting on my top hat, tying up my white tie and brushing off my tails. Are you ready to breathe an atmosphere that simply reeks of class?

Fredo

PS:

Q. What was the Number 1 movie at the box-office in 1935?

A. It was Mutiny on the Bounty starring Clark Gable and Charles Laughton.

Group Visit:

Tuesday 16/12/25

7.30pm performance

at the

Donmar Warehouse

Playwright: J B Priestly>

WHEN WE ARE MARRIED

There’s a major gap in my eduction: I’ve never read a novel by J B Priestly. No, not even The Good Companions, a best-seller in 1929 and scarcely out of print since then. I’m assured by a trusted friend that this picaresque tale of a travelling company of players is a page-turner, but I’ve let it slip through my fingers.

Is it the fate of writers who were popular and influential in their own time to fall out of fashion if they outlive their moment in the spotlight? If so, the case of John Boynton Priestley is more mysterious than others. He was born, as he would have you know, in an “extremely respectable” suburb of Bradford in 1894. His father was a headmaster, and his mother worked at the mill, but she died when he was 2. Despite his talent and ambition. he left school aged 16, and went to work as a clerk. It was then that he started to have articles published in the local and national press.

The war interrupted his literary career. He was badly wounded in 1916, and later suffered from the effects of poison gas. After he was demobilised in 1919, he went to Cambridge. He got married and had two daughters, but his wife died four years later, in 1925. At this point in his career, he had gained a national reputation as an essayist and critic.

When did he find time to write so much? Novels and plays poured out of his pen, yet he also remarried and had a tempestuous affair with Peggy Ashcroft. Despite this, his second marriage lasted 27 years till 1953. In the meantime, he made a major contribution to maintaining morale during the Second World War by making broadcasts on the BBC. His popularity almost equalled Churchill’s, and it was rumoured that Churchill had Priestley’s broadcasts cancelled as he was jealous. A more likely reason is that the cabinet disapproved of the left-wing flavours of his speeches.

Perhaps his most lasting achievement was his 1945 play An Inspector Calls. Written in a single week, a suitable venue couldn’t be found to present this play in Britain, as all the theatres were booked for the season. Strangely, it went on to have its first performances in Moscow and Leningrad. It was staged in London the following year, as a fairly conventional drawing-room drama, but with a mysterious twist.

During the 50s, with the new wave of realist drama, An Inspector Calls and Priestley’s earlier domestic dramas, such as Eden End and Time and the Conways, fell out of fashion. Priestley seemed to be regarded as yesterday’s man, and though his novel Lost Empires sold well and was dramatised for television, it didn’t restore his popularity or reputation. He seemed to be patronised by generation that wasn’t aware of his earlier achievements. However, in 1992, director Stepen Daldry, and presented it in a revolutionary production at the Lyttelton Theatre. Daldry revealed the play as an indictment of a smug, enclosed society, and sent shock waves through the audience. On our visit, one younger member of the Group told me that towards the end, she suddenly wanted to cry, without understanding why she felt that way. This production has had a long afterlife, and the play was added to the GCSE syllabus.

Meanwhile, Priestley’s 1938 comedy When We Are Married has always retained its place in audiences’ affections. Again written at speed, this one was close to Priestley’s heart:

“I had long wanted to write a funny play about the Yorkshire I had known as a boy, thirty years ago; so I took three couples, made it their silver wedding celebration, sketched in one or two scenes of genuine comedy … and then, trying to remember every droll thing about that old Yorkshire, I let it rip.”

Since its first production (when the cast included Patricia Hayes in a small part), When We are Married has had countless revivals – we’ve taken groups to see it at least three times. It’s been described as a Rolls Royce of a play, as every part runs smoothly, like a well-oiled machine.

The Artistic Director of the Donmar, Tim Sheader has an interesting angle on it. He compares it to A Midsummer Night’s Dream: we’re presented with three couples, and in the course of a few hours, they experience upheavals, transformations and reversals. They emerge with a different perspective and an adjustment to what they have learned about themselves. I cannot disagree with that summary – except that I’ve always found it much funnier than any of Shakespeare‘s plays.

Perhaps we’re due for a Priestly revival. Penguin has just republished his first novel, Benighted, which was famously filmed as The Old Dark House – yes, it’s a horror story, not to be read late at night, and I won’t start with that one. If they reprint The Good Companions, I’ll have no excuse. I’ll just have to get down to it.

First of all, I’ve got When we Are Married to look forward to.

Fredo

Group Visit:

Tuesday 09/12/25

7.30pm performance

at the

Menier Chocolate Factory

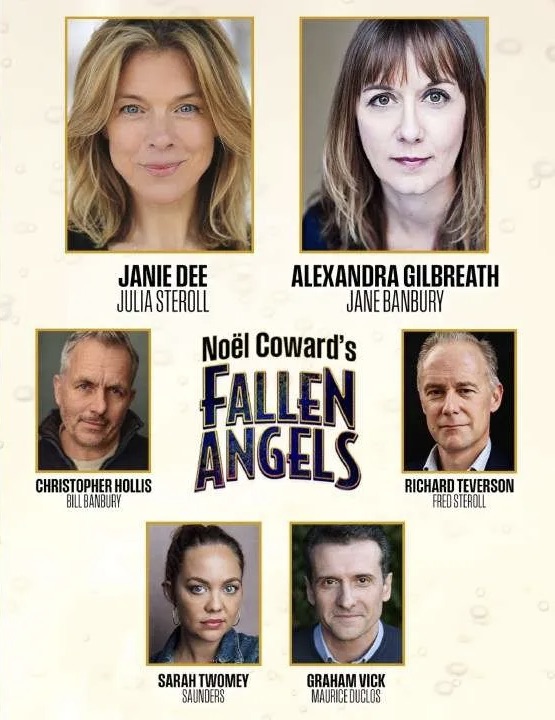

The cast: click to enlarge

“At least this one’s as clean as a whistle,” Noel Coward informed the audience at his curtain call for Hay Fever. The 25-year-old playwright had created a scandal with his previous success The Vortex, with its drug-taking, louche sexuality and a hint of incestuous passion between the mother and son.

Coward’s career was in the ascendant. He’d been a child actor, a dancer, a contributor to revues both as a writer and songwriter. He’d written several plays, some of which are being rediscovered with claims that they show early signs of genius (they don’t). The quantity of his output was unimpeded by quality control, but he was learning his craft.

His next play in 1925, Fallen Angels, caught the eye of the glamorous actress Gladys Cooper, who want to produce it for her own company at the Globe (now the Gielgud) Theatre, and to appear in it opposite the popular Madge Titheradge.

Coward in 1925

However, there was a difficulty: Hay Fever may have been squeaky clean, but Fallen Angels wasn’t. It lacked the heightened melodrama of The Vortex, but a subordinate in the Lord Chamberlain’s office objected to the idea of two women friends who’d had a sexual affair with the same man before they married (though presumably not at the same time) and who now eagerly await his return. And it didn’t even take itself seriously; it’s a comedy!

Fortunately, the Lord Chamberlain intervened. Though not known for his sense of humour, he considered it lightweight enough to do no harm, and granted it a licence. I suspect that Coward’s friends in high places may have pulled a few strings.

By now, Cooper and Titheradge have other commitments. Cooper later went to Hollywood, where she cornered the market in strict matriarchs in films such as Now, Voyager, The Bishop’s Wife and Separate Tables, picking up three Oscar nominations along the way.

The rights to the play passed to another actress/manageress, Marie Lohr, who staged it as a vehicle for another popular West End star, Margaret Bannerman, with Edna Best. Unfortunately, four days before opening night, Miss Bannerman was forced to withdraw due to illness.

This was unfortunate for Miss Bannerman, but possibly it was a stroke of luck for the play. The 23-tear-old American actress Tallulah Bankhead had created a sensation in the West End, and she was available. Furthermore, she had a photographic memory and was a quick study. Most importantly, she was temperamentally suited to the play.

Tallulah – she was one of those actresses who was so famous that her first name was enough – was the scion of a notable Alabama family. Her grandfather and uncle were US senators, and her father was the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Her family supported liberal causes, Young Tallulah was brought up by her grandmother, as her mother died when she was three weeks old. Chronic bronchitis in her childhood left her with a distinctive – and much-imitated – deep voice.

Tallulah in 1925

She was spotted in a photographic competition and went to New York to take up a career on stage. Her father advised his young daughter to avoid alcohol and men, and Tallulah later quipped, “He didn’t say anything about women and cocaine.” She was energetically bisexual, and was adamant that cocaine wasn’t habit-forming – “I should know. I’ve been using it for years.”

Dissatisfied with the plays she appeared in on Broadway, Tallulah moved to London in 1922. She immediately caused a stir, and attracted a large following of ardent fans. In the next 8 years, she appeared in 12 plays. She brought a hint of scandal on to the stage of Fallen Angels.

After her success in London, Tallulah went to Hollywood, and though she made several films – most notably, Lifeboat, directed by Alfred Hitchcock – she was bored and didn’t fit in. Despite an impressive screen-test for Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind, by 1938 she was considered too old for the part.

She had notable successes on Broadway with Jezebel, The Little Foxes and The Skin of Our Teeth, but it must have been galling to see her roles go to Bette Davis when they were filmed.

Some years later, Mike and I met a lady who had briefly been employed as Tallulah’s housekeeper. (But that’s another story!) At that point in her life, alcohol and cocaine had taken their toll. She was still a quick study: she could read a script and rehearse it front of the mirror right away. She was generous to a fault, and would post off cheques to families in need. Her behaviour was erratic, and our friend found other employment after Tallulah set fire to the apartment by falling asleep with a lighted cigarette.

All that was in the future at the first production of Fallen Angels. I read the play when I was still a teenager, and I thought it was very funny. I was surprised to find how seldom it had been revived, considering that we never seem to be more than a year away from revivals of Hay Fever, Blithe Spirit or Private Lives. It certainly requires stylish performers, but there is no shortage of those. In 1949, it was presented at the Ambassador’s Theatre with Hermione Gingold and Hermione Baddeley, and again in 1967 with Joan Greenwood and Constance Cummings. Then it disappeared until 2000, when Felicity Kendall and Frances de la Tour starred in it.

It’s been televised twice, with Ann Morrish and Moira Redmond in 1963, and again in 1974, with Joan Collins, Susannah York and Sacha Diestel as the yearned-for lover. Perhaps its moment has come at last, for as well as the production at the Menier, it’s listed for Broadway next year with Kelli O’Hara and Rose Byrne.

Although Coward is highly regarded as The Master, his output was extremely uneven. At his best, no-one did it better: Private Lives is a classic, and David Lean’s film of Brief Encounter explores Coward’s study of repressed passion better than any other movie of the period. But then there’s The Astonished Heart, which is toe-curlingly embarrassing, and the atrophied snobbishness of Relative Values is difficult to overlook.

Fredo

Group Visit:

Tuesday 25/11/25

7.30pm performance

at the

Soho Place Theatre

Charing Cross Road

Novelist:

John le Carré

Adapted by:

David Eldridge

Fredo introduces THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD

You’ll need to be on your toes for this one. There are twists and turns, betrayals and disinformation throughout David Eldridge’s adaptation of John le Carré’s bestselling novel. Stay awake!

During the Cold War, and shortly after the building of the Berlin Wall, MI6 considers that their West Berlin office is suffering from reduced effectiveness. The station chief, Alec Leamas, is brought in from the cold and recalled to London. He wants out, but he is entrusted with one last mission: return to Germany as a defector and plant misleading information about a powerful East German officer. He’ll get his reward: retirement and a pension – but can he trust the Circus to give him the back-up he needs?

This was a world that John le Carré knew from the inside. He had been recruited for MI5 while studying languages at Oxford. He had already served in the Intelligence Corps in allied-occupied Austria in 1950, interrogating defectors who had crossed from behind the Iron Curtain. He then taught French and German at Eton for two years, before joining MI5 as an officer in 1958. In this capacity, he ran agents, conducted interrogations, tapped telephones and effected break-ins.

In 1960, he transferred to MI6 and worked undercover at the British Embassy in Bonn. However, his career ended abruptly because of the treachery of Kim Philby.

As a married man with three sons to support, le Carré started his writing career. His first two novels Call for the Dead (1961) and A Murder of Quality (1962) were aimed at the lucrative crime fiction market, and though there was an espionage twist, they were primarily whodunnits. However, they introduced George Smiley as a minor character, and he later developed into le Carré’s major creation.

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold followed in 1963, and this was a huge departure from the usual run of British spy fiction, such as The Thirty-Nine Steps or the glamorous and violent world of James Bond. It also represented a massive leap from his first two novels. The story was more convoluted, and blended moral and ethical considerations into the cloak-and-dagger mix. It caught the spirit of the time, and was an immediate hit. It even introduced a new vocabulary into spy fiction: “the Circus” was HQ (presumed to be located in Cambridge Circus, but with a sense of ring-masters and clowns as well) and moles were secret agents.

The success of the novel made his name and reputation. George Smiley is a secondary character here as well (he takes centre-stage in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) but the novel focuses on the predicaments of Alec Leamas, who asks: “What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not. They’re just a bunch of seedy squalid bastards like me, little men, drunkards, queers, henpecked husbands, civil servants playing “Cowboys and Indians” to brighten their rotten little lives.”

Rory Keenan is Alec Leamas in The Spy…

The success of the novel made his name and reputation. George Smiley is a secondary character here as well (he takes centre-stage in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) but the novel focuses on the predicaments of Alec Leamas, who asks: “What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not. They’re just a bunch of seedy squalid bastards like me, little men, drunkards, queers, henpecked husbands, civil servants playing “Cowboys and Indians” to brighten their rotten little lives.”

The Spy…. was filmed with Richard Burton, Claire Bloom and Rupert Davies (Maigret) as Smiley. There was tension on the set, as Burton clashed with director Martin Ritt, and Elizabeth Taylor, knowing that Burton had had an affair with Claire Bloom some years previously, hovered around anxiously. It was a hit at the box-office. Several of le Carré’s other novels have been filmed or televised – notably, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier. Spy and The Night Manager – but this is the first one to be adapted for the stage.

One of my retirement projects was to read the George Smiley novels in sequence, but it didn’t work out. It turns out I have a blind spot for spy fiction, and I couldn’t work out what was happening from page to page. Perhaps I’ll see the light at the play; if not, would a kind person explain it all to me?

Fredo

Group Visit:

Monday

10 November 2025

7.30pm performance

at the

Donmar Warehouse

Playwright:

Jean Genet

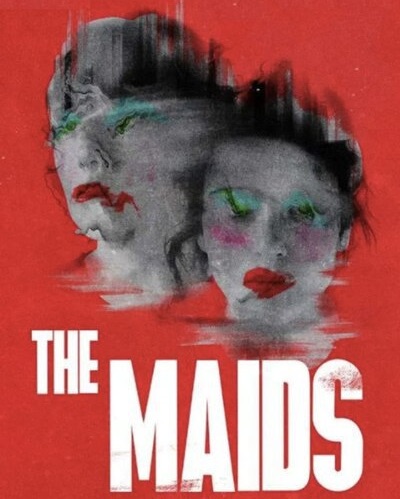

It’s like a children’s game: “I’ll be Mummy, and you’ll be me, and you have to do everything I say.”

To sisters Claire and Solange, it isn’t a game but a ceremony that they enact when their mistress Madame is out of the luxurious apartment. They take turns as Madame, who in this game abuses her maid. It won’t end well.

This evening the stakes are high, as Claire has shopped Madame’s lover to the police, and he has been arrested. Just before Madame arrives home, Monsieur phones to say that he’s out on bail. Knowing that their betrayal will be discovered, there’s only one solution: they must murder Madame.

Though he based it on a real-life murder in Le Mans in 1933, Jean Genet created his own world of shifting power-play and role-swapping in this complex drama. Are the maids representative of an oppressed class who rebel against their submission? Are they craving a life that they have been denied by subjugation to a corrupt social order? The French word for Maids – Les Bonnes – also translates as “The Good Women”; is that in fact all they are, but misplaced in intolerable circumstances?

At the Donmar, director Kip Williams adds further layers to Genet’s already complex text. At the start, the sisters’ ceremony is shrouded by heavy net curtains (perhaps for too long), enclosing them in their private, shared fantasy. Their role-playing is enhanced by their use of appearance-altering filters on their cell-phones (projected onto background mirrors). It’s a confusing descent into their morbid imaginings, only clarified by the return of Madame.

In this version, Madame is a younger woman (in fact, all three actresses are young, though the maids are described by Genet as older and unattractive) who seems to have found fame and fortune as an influencer. Her boudoir is filled with flowers sent by well-wishers. Her wardrobe is stuffed with designer clothes, wigs, accessories and jewels. It’s claustrophobic and stifling for the three women – a reminder of Jean-Paul Sartre’s observation that Hell is other people.

With Madame’s decision to leave and return to her lover, Williams raises pressure on the cast and the audience – the maids rush headlong to fulfil their destiny. It’s mind-blowing and exhausting.

At the Supporters’ Evening Q&A with the cast, the actresses Yerin Ha, Phia Saban and Lydia Wilson told us that Kip Williams encouraged them to give big performances – and they oblige. They said they can always sense if there’s a feeling of resistance in the audiences as they explore the play’s themes of idolisation and of the impulse to destroy. My advice is to go with the flow; don’t fight back.

Is this what Genet would have wanted? Not entirely, because he never really got to see The Maids produced as he wished. His idea was that the three women should be played by men, but this direction has only been followed in very few productions (Mark Rylance has played Madame). In fact, productions of Genet’s plays are rare, because of the contentious themes and the difficulty in staging them.

His emergence as a writer was torturous. He was born in 1910, and as his mother was a prostitute, he was given up for adoption at 7 months. Although he was clearly an intelligent pupil at school, at the age of 15 he was sent to a penal colony for petty theft and vagrancy. On his release, he joined the French Foreign legion aged 18, but was dishonourably discharged when he was discovered in a homosexual act. He resumed his career as a vagabond, petty thief and homosexual prostitute across Europe, but in France he introduced himself to the writer and artist Jean Cocteau.

Even then, his criminal career continued till he was threatened with life imprisonment for 10 convictions. Cocteau, Sartre and Picasso petitioned for his sentence to be set aside; he never went to prison again. Instead he made his name as a novelist and dramatist, and in later life, espoused left-wing political causes.

His reputation rests on a slender body of work, and this is a rare example to enter his individual world. Whether or not it’s a version of that world that Genet himself would recognise is a matter for debate – but you can enjoy the ride.

Fredo

Group visit:

Tuesday

4 November 2025

PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS EVENING’S PERFORMANCE BEGINS AT 7.00pm.

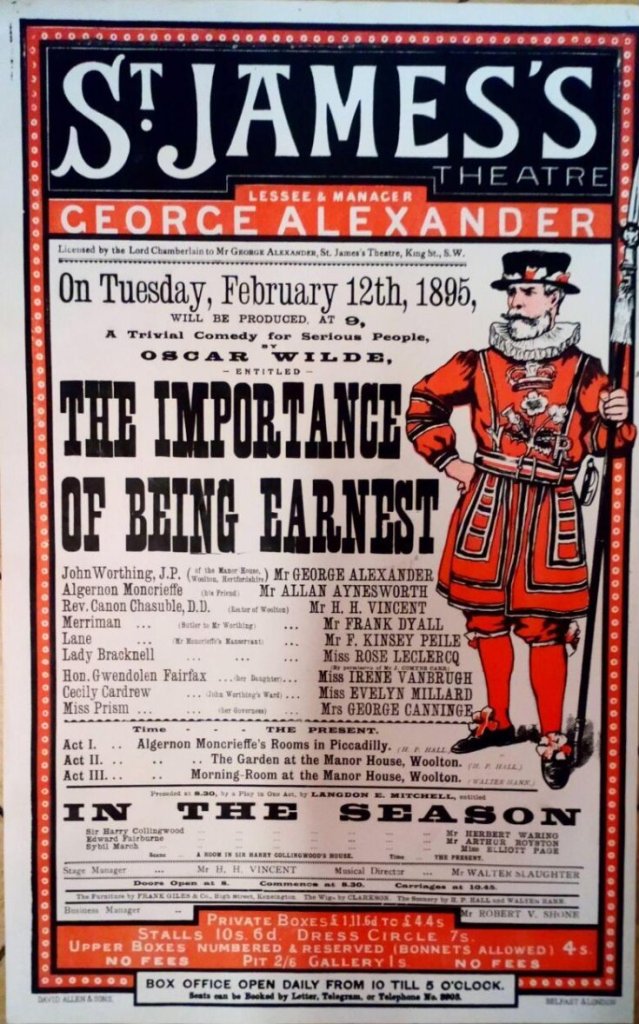

OSCAR & THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST

Yes, it is more than just a collection of Oscar Wilde’s best-known witticisms. You’ll have heard some of the lines before, and it must be tempting to the actors to offer each one up like a multi-faceted ruby on a cushion.

Comedy doesn’t work like this. It needs context, and Wilde provides a plot that is as intricate as clockwork. The situations are complex and become more so as the play progresses. The aphorisms adorn the dialogue like lights on a Christmas tree.

Before writing this play, Wilde was celebrated for three “social comedies”, written and staged in quick succession: Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance and An Ideal Husband. Each yields up its fair complement of bons mots, but they have their roots in Victorian melodrama. It was perhaps Wilde’s great theatrical innovation to blend comedy into this form of drama, and to add an element of social criticism as well: all three plays contain a fallen woman, who has suffered more than the man who did her wrong.

Although he subtitled Earnest as “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People”, Wilde constructed basically a comedy of manners in the form of a farce underpinned with shafts of social satire and burnished with his immaculate prose.

The plot is too involved to summarise. Each of its three acts have a comic momentum, and contain a set-piece that has become a classic: the formidable Lady Bracknell’s interview with John, then the tea-party with Gwendoline and Cecily, and finally John’s frantic off-stage search for the famous handbag. However, much has been made in recent years of the double-life of the two young men and the fictitious alibi Bunbury. Wilde himself led a double-life; let’s have a look at that.

We find immediate contradictions in the mythology of Oscar Wilde. A major English dramatist, who was actually Irish, a hugely famous and handsomely-rewarded journalist, essayist, novelist and playwright who died in ignomiy and poverty, a husband and father seduced into promiscuous gay relationships. Where did it all go wrong?

He was born in Dublin in 1854, son of Sir William Wilde, an eye and ear surgeon. His mother Jane had strong nationalist views and wrote poetry on this theme under the pen-name Speranza. They lived in fashionable Merrion Square (the Eaton Square of Dublin). Wilde attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen (my home-town)and then went to university at Trinity College, Dublin and later to Magdalen College, Oxford. His childhood sweetheart was Florence Balcomb, but she married Bram Stoker, author of Dracula and manager of the Lyceum Theatre.

He embraced the Aesthetic Movement, with its cult of beauty for its own sake, and lectured in this subject. He was a large man, and not especially handsome; with his flamboyant appearance, he wouldn’t have been overlooked. Gilbert & Sullivan parodied him in their operetta Patience. Wilde, in turn, borrowed from W S Gilbert’s play Engaged for Earnest.

Marriage to the beautiful and talented Constance Lloyd didn’t calm him down. A woman of note in society for her own journalism and progressive views, Constance seemed the ideal companion – though they lived beyond their means in Tite St, Chelsea. They were the centre of their social circle which included Lillie Langtry and the artist James MacNeil Whistler.

However, the passion between them cooled after the birth of their second son, and Wilde spent more time living in hotels.

This was possibly connected to his meeting the young Robbie Ross in 1886. Wilde was 32 and Ross was 17, but it was the younger man who seduced the older. This heady mixture of forbidden sexuality and wantonness combined with his aesthetic philosophy found expression in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. Although Ross set Wilde on the road to his destruction, it’s important to note that he remained a loyal friend to both Osacr and Constance in the difficult years that followed.

The significant encounter in Wilde’s downfall happened five years later. Lord Alfred Douglas – Bosie to his friends – was 21 and a gilded youth. He was estranged from his father, the brutish Marquess of Queensberry, and Wilde was infatuated with him. He indulged Bosie’s every whim, emotionally, sexually and financially. Rumours of the relationship reached Bosie’s father, who physically threatened Wilde on several occasions.

Queensberry threatened to create a scene at the opening night of The Importnace of Being Earnest at St James Theatree. Wilde had him banned from entering, but two weeks later, he left a note addressed to Wilde “posing as a somdomite” – yes, Queensberry was better at boxing than at spelling! Wilde sued for libel.

In the case of Wilde v Queensberry, the latter was represented by Edward Carson, an acquaintance of Wilde’s from Trinity (who later was active as a Unionist politician in Ireland, opposing Home Rule). Wilde’s performance in court was slick and witty – too witty, and with a slip of the tongue, lost his case.

It was clear that Wilde would be prosecuted, but he resisted the advice of Ross and other friends to flee to France. He was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel, and charged with gross indecency. The jury in his trial failed to reach a verdict. In a second trial, he was sentenced to 2 years hard labour. Most of this was served at Reading Gaol. While there, he wrote a long letter to Bosie, which was later published under the title De Profundis (From the Depths). Bosie did not visit him, and Constance came to tell him of his brother’s death.

When Wilde was released in 1897, he went to France. Constance offered to support him, on condition that he did not see Bosie, but Wilde was unable to break the hold that the dissolute younger man had on him. He died in Paris in 1900 from meningitis.

Constance had died two years earlier. She changed the family name to Holland, and the opprobrium that dogged her husband followed her. One night she was recognised by an English couple in a hotel in France, and they demanded that she and her two young sons should be evicted.

Robbie / Bosie

Bosie with Oscar

When the scandal of Wilde’s trials erupted, the theatres presenting his plays removed his name from the posters and programmes. It wasn’t many years before his name was restored and the plays have been presented and enjoyed regularly ever since. His influence stretches through Noel Coward to Joe Orton and beyond.

In 2017, Wilde and other men who had been prosecuted for gross indecency were given a posthumous pardon. Recently, Oscar’s grandson Merlin Holland wrote a memoir entitled After Oscar. I happened to be in the John Sandoe bookshop in Chelsea when Mr Holland was standing over a tower of his books, signing copies that had been pre-ordered, and discussing the first Japanese translation of De Profundis.

This production by Max Webster boasts Stephen Fry as Lady Bracknell. It seems to have become a tradition in the last twenty years to cast this role with a male actor (David Suchet has played it as well). Fry has form with Oscar, having given a very sympathetic portrayal of him in the film Wilde. It’s a triumphant celebration of one of the great comedies, and an illustration of the Importance of being Oscar.

Fredo

Group visit:

Monday

27 October 2025

7.30pm perf

Director: Tom Morris

Music: P J Harvey

The academics fret about Othello. What is Iago’s motivation? Why is the time-span so compressed ? How could Othello be so gullible?

None of these questions seem to exercise audiences. The plot is straight-forward, the language direct, the characters are driven by clear motives, which they make explicit:

Iago is angry that Cassio has been promoted above him, and he is jealous of his commander Othello, who he thinks may have seduced his wife Emilia. He takes his revenge by plotting to destroy Othello, by planting seeds of doubt about Desdemona, Othello’s young wife. Othello’s descent into madness leads to the tragedy of the play.

Shakespeare wrote the play in 1603, at the height of his power as a dramatist, and it is ranked with Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear as the four tragedies that constitute his greatest achievement. Of the four, it’s the one that (in my experience) works most reliably in performance. There are no tiresome “comic” scenes, no distracting sub-plots. The action is focused and moves swiftly from the start.

It starts in Venice, where the needs of the state take precedence over the disturbance of Desdemona’s elopement with Othello. He’s a general, the state needs him, his wife loves him, that’s all the Senate needs to know.

However, things change rapidly when Othello takes up his post in Cyprus. There’s a storm at sea; the ship carrying Desdemona comes into harbour before he arrives. It’s the first disturbance, and an indication that we’ve entered a more uncertain, dangerous world. Iago’s contrivances soon erode the security of the Venetian state.

Ambassadors arrive from Venice, and observe scenes of domestic violence, as Othello is reduced to madness. Ever faithful, Desdemona takes no precautions to protect herself from the violence that ensues.

In almost all his work Shakespeare explores a disturbance that has to be resolved by the play’s end. In Hamlet, the state of Denmark is excised of corruption and will be ruled by the Norwegian Fortinbras; the rightful king of Scotland will take the throne in Macbeth. In Othello, the civil rule of Venice is imposed as the play ends, but the innocent have suffered. It’s a domestic tragedy, elevated by Shakespeare by exploring the difference between the control of the state and unbridled, primal passions.

The role of Othello has always been a challenge to actors, especially in the days when white actors had to black up to play it. It’s many years now since that happened, and when Michael Gambon was announced for the role, the project was quietly cancelled. There are many black actors with the talent and stature to play the role, without the distraction for the audience of wondering if the actor was convincing as a Moor as well as a plausible Othello.

David Harewood takes the title-role in this production, and it’s the third time he’s played it – the previous incarnations were for the RSC in 1991 and the National in 1997. He’s joined by Toby Jones as Iago. Tom Morris, co-director of War Horse, is in charge of the production.

In the opera Otello, Verdi dispenses with Shakespeare’s first act and starts the action with the ships arriving in Cyprus across the turbulent seas. There’s no overture – we’re plunged dangerously into the action. One of my English tutors considered this to be an improvement on Shakespeare, but I don’t agree. The contrast between the two worlds of the play adds a dimension.

You’ll leave the theatre talking about Othello –

Then must you speak

Of one that lov’d not wisely, but too well…..

Of one whose hand,

Like the base Indian, threw a pearl away

Richer than all his tribe.

There are several reasons why The Unbelievers is sold out for its entire run at the Royal Court, even before it opens.

It’s a new play by Nick Payne, who created a stir as a young writer with his hugely successful play Constellations. This transferred from the Royal Court to the West End, and subsequently to New York. The director Michael Longhurst used it to kick-start the Donmar after the pandemic by presenting it as a Donmar production in the West End for a short season, and with different casts. I have some affection for Nick Payne, as he did a very gracious favour for me. The evening we took the group to see his play Elegy at the Donmar, I had arranged for two of the cast members to join us for a Q&A. Mike and I met Nick in the bar beforehand and mentioned this to him. He had planned to meet friends after the play; nevertheless, he joined the actors on the stage, and I was thrilled to have the playwright in person join us to discuss his work.

Another reason is that the new play is directed by Marianne Elliott, and despite her formidable body of work, she will always be remembered as the director of War Horse and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. Both these productions broke new ground in telling stories on stage, and while their technical innovations were rightly acclaimed, Marianne’s strength is her ability to unfold a narrative clearly. Her productions have ranged from St Joan at the National to Stephen Sondheim’s Company in the West End and on Broadway. She’s the only woman to have won three TONY Awards.

The star of the show is Nicola Walker. She has worked her way steadily to the forefront of leading television actresses, with her winning combination of warmth and insecure edginess. Her series Spooks, Unforgiven, Last Tango in Halifax and The Split have won huge audiences. Her emergence as a star on stage has been more tentative, with supporting roles in A View from the Bridge and Curious Incident. There the odd misfire in the eccentric production of The Corn is Green at the National, but that wasn’t her fault. Earlier this year, she and Stephen Mangan kept the tricky subject of Unicorn aloft; I can’t think of another two actors who could have pulled that off.

The Royal Court tells us little about the play, except it’s about the moments that shatter our world, and the ones that help us piece it back together. My friend Elizabeth has seen it, and was impressed, but won’t divulge further information.

Wait and see!

The full cast is Esh Alladi, Alby Baldwin, Paul Higgins, Ella Lily Hyland, Martin Marquez, Harry Kershaw, Lucy Thackeray, Nicola Walker and Isabel Adomakoh Young.

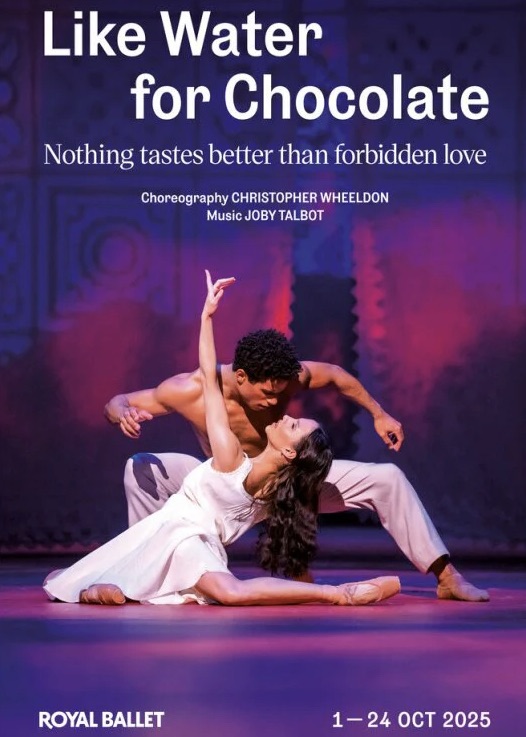

SYNOPSIS

Fifteen-year-old Tita lives on a ranch with her domineering mother, Mama Elena, her older sisters Gertrudis and Rosaura, and Nacha, the ranch cook. Tita has a deep connection with food and cooking thanks to Nacha.

Tita falls in love with their neighboUr Pedro. He asks Elena for Tita’s hand in marriage. She forbids it: according to a tradition of the family, the youngest daughter must remain single and take care of her mother until her death. She suggests that Pedro marry Rosaura instead. In order to stay close to Tita, Pedro agrees.

While preparing Rosaura’s wedding cake, Tita is cries into the cake batter. Nacha tastes the cake, and suddenly is overcome with grief at the memory of her lost love. At the wedding, everyone except for Tita gets violently sick after eating the wedding cake. Afterwards, Tita finds Nacha lying dead on her bed, holding a picture of her fiancé.

Rosaura gives birth to a son, Roberto. She is unable to nurse him so Tita tries to feed Roberto herself. Miraculously, she begins producing breast milk and is able to nurse Roberto. This brings her and Pedro closer than ever. They begin meeting secretly around the ranch.

Rosaura, Pedro and Roberto move to San Antonio at Mama Elena’s insistence. Roberto dies soon after the move. Upon hearing of her nephew’s death, Tita loses her mind. John Brown, the widowed family doctor, takes her back to his home to live with him and his son, Alex.

Tita and John soon fall in love, but her feelings for Pedro do not waver. At the ranch, a group of bandits attack the ranch and paralyse Mama Elena. Tita returns to take care of Mama Elena. However, Mama Elena is paranoid that she is poisoning her out of spite.

After Mama Elena’s death, Tita accepts John’s marriage proposal. Pedro, Rosaura, and their daughter Esperanza return to Mexico, and Tita loses her virginity to him. She grows anxious that she is pregnant with his child. Her mother’s ghost haunts her, telling her that she and her unborn child are cursed. Tita confirms that she isn’t pregnant and banishes her mother’s ghost from her life for good, but the ghost takes revenge by setting Pedro on fire, leaving him badly burnt and bedridden, although he recovers. Tita rejects John, informing him that she cannot marry him due to her affair with Pedro.

Many years later, Alex Brown and Esperanza get married. During the wedding, Pedro proposes to Tita.

HOT CHOCOLATE

When I read Layra Equivel’s international bestseller in 1992, I’d never come across a book like it before. It mimics the format of a monthly women’s magazine, with recipes and a highly romantic and melodramatic plot, and it’s a page-turner. It was the sort of book you’d beg your friends to read, and give it to them at Christmas with a tin of cocoa. (In Mexico, hot chocolate is made with water, not milk.)

Blended in with the Chocolate, there was a strong flavour of magical realism. This was a literary innovation that flourishes in Latin American and Asian novels in the 80s, and it’s simply the introduction – and acceptance – of supernatural or magical elements in everyday settings. The best example is perhaps when Tita cooks quail in rose petal sauce.

She pours her intense emotions into her cooking, unintentionally affecting those around her. Gertrudis becomes so inflamed with lust that she sweats pink, rose-scented sweat; when she goes to cool off in the shower, her body gives off so much heat that the shower’s tank water evaporates and the shower itself catches fire. As Gertrudis runs out of the burning shower naked, she is carried away on horseback by revolutionary captain Juan Alejandrez, who is drawn to her from the battlefield by her rosy scent; they have sex atop Juan’s horse as they gallop away from the ranch.

Follow the recipe in the book and see what happens.

ADAPTATIONS

There’s a lot of story in Laura Esquivel’s book, and it has been adapted as a movie, a television series (twice), an opera, a musical and now a ballet. It should be spectacular. Let’s enjoy it!

In All About Eve, Bette Davis played an actress rehearsing a play. It isn’t going well, and she storms off the stage, shouting “When do writers start thinking that they’re Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Beaumont and Fletcher?” The playwright yells after her, “You stick to Beaumont and Fletcher – they’ve been dead for 300 years.” Bette whirls round, and delivers (as only she can) the death-blow: “ALL playwrights should be dead for 300 years.”

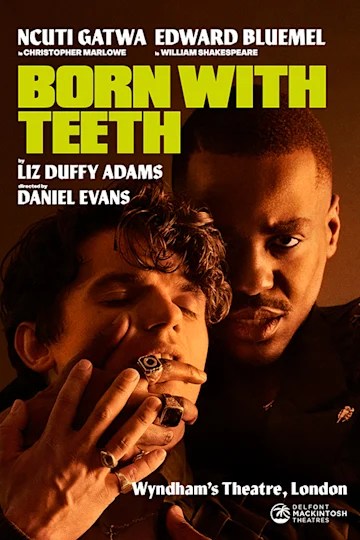

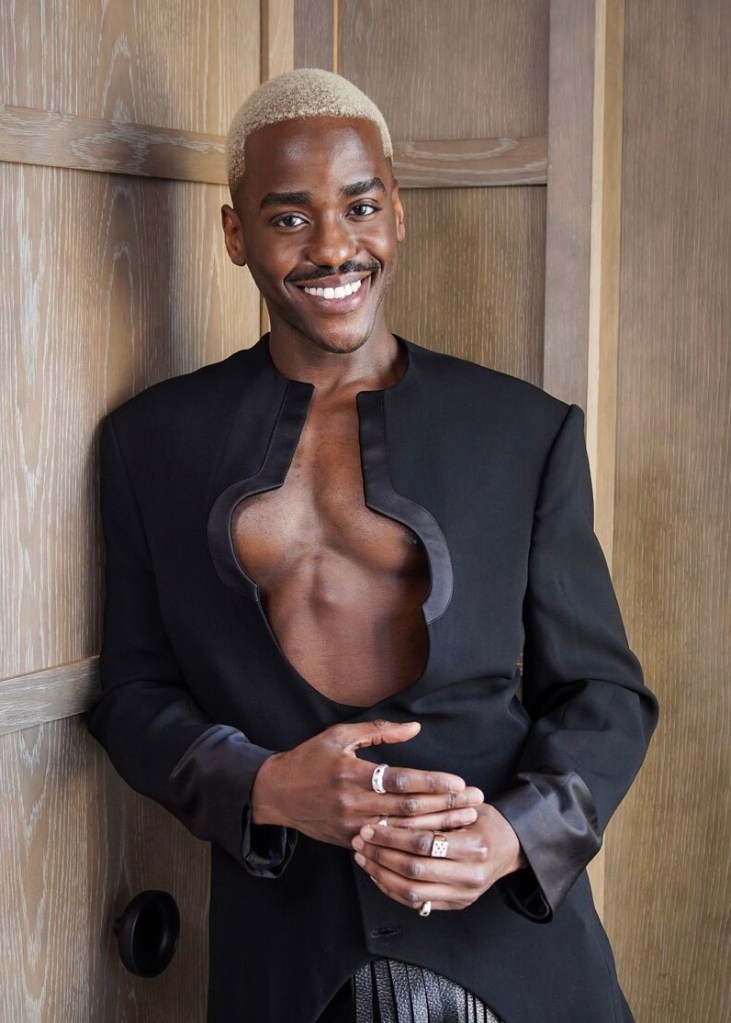

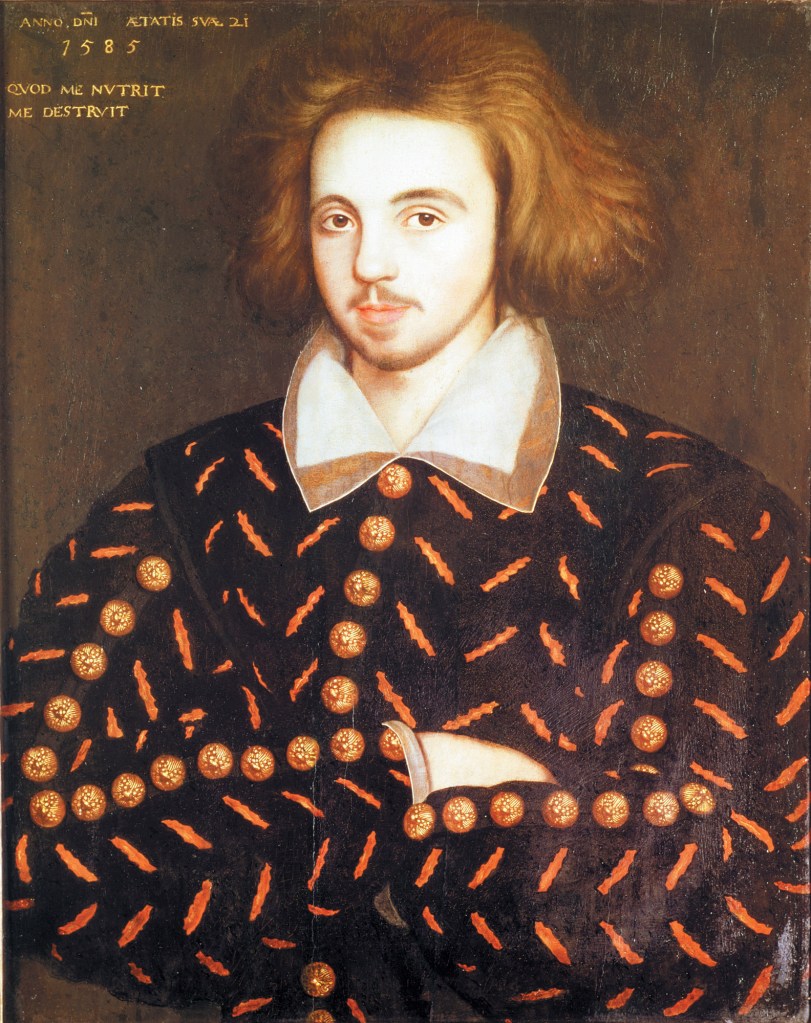

Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare have been dead for 400 years, but they are brought to full-blooded life in Born with Teeth by Liz Duffy Adams. The work of this prolific American dramatist is presented in this country for the first time by the Royal Shakespeare Company, directed by Daniel Evans. He’s gifted Ms Adams a memorable production- sharp, funny and light on its feet.

We meet them when Marlowe is revelling in his success, and is about to collaborate with this young apprentice from the country on his early play about Henry Vl. There’s a certain amount of sparring and not a little flirtation. As Marlowe, Ncuti Gatwa flaunts his sex-appeal (the leather trousers help), while Edward Bluemel exudes a more malleable sexuality. There’s a suggestion that there’s something for everyone here.

In three short scenes, Henry Vl is written and despatched, and is so successful, there are two sequels; it’s the Star Wars of its day. The power balance between these two ambitious rivals shifts; pay close attention to the third act, where reversals occur. (The play is performed without an interval and lasts about 90 minutes.)

I enjoyed this play, and my hard-to-please friend Catherine did as well. We were surprised that it wasn’t more warmly embraced by the critical fraternity.

It may help to have a nodding acquaintance with Elizabethan drama, a period when the theatres were packed and the audience was hungry for fresh material. The undisputed leading writers were Marlowe and Ben Jonson, whose city comedies The Alchemist and Volpone are regularly revived today. Marlowe hasn’t fared so well. Doctor Faustus, the story of the man who sells his soul to the devil, crops up from time to time, and though the National Theatre opened on the South Bank with a huge production of Tamburlaine the Great, with Albert Finney, it hasn’t been heard of since.

Revenge tragedy was popular, and Shakespeare toyed with this genre, as we witnessed recently with Titus Andronicus. The main proponents were Thomas Kyd with The Spanish Tragedy and John Marston with The Malcontent. Again, these plays enjoyed a brief recall to life at the National and the RSC, but seem to have been returned to academic libraries to gather dust on the shelves.

There’s a case to be made for Hamlet as a Revenge tragedy, but let’s agree that this play transcends any categorisation.

Perhaps Born with Teeth will rekindle interest in this period. At least it serves as a launch-pad for two eye-catching young actors.

Fredo

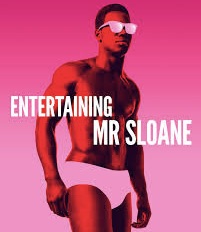

“This is my lounge” announces Kath to her new lodger Mr Sloane, and in the same breath Joe Orton announces that his play is a satire on the conventions and conformities of England in the 60s. Sloane is an outsider. There’s something edgy and slightly sinister about him that Kath doesn’t recognise. Her sexual dial wavers between Will and Must, and she doesn’t realise that this makes her vulnerable to this apparently nice young man.

It’s an indication of the dramatist’s skill that he can present Kath as a pretentious and ridiculous figure, but later expose the insecurity and pathos that lies underneath this armour. There are unexpected developments, and reverses of sympathy, before the intriguing end.

Joe Orton went on to ruffle feathers with Loot, a farce that incorporated various taboos and shibboleths into its hilarious action. He had created a scandal with Sloane, tinted in darker shades, with its hints of forbidden sexuality. Nevertheless, it was championed by Terence Rattigan, who sponsored its transfer from the Arts Theatre to Wyndham’s with a gift of £3,000.

Orton’s reputation as a provocateur was confirmed when details of his private life emerged – he was murdered by his lover Kenneth Halliwell in 1964, aged 34. The posthumous production of his final, unrevised play, What the Butler Saw, was a legendary disaster, because of miscasting in the leading role and hostile audiences.

The fortunate sequel to these events was the quick reassessment of Orton’s body of work. Comparisons were drawn with Wilde and Coward, and indeed his dazzling wit and use of language justifies this. The underlying tone of menace suggested the influence of Pinter, though both writers were close contemporaries. All this seems to me to be a defence of the playwright rather than a celebration of his unique voice, and the care that’s evident in the construction of his plays. In his study of Orton’s plays, I think that John Lahr overstates his case for What the Butler Saw. There are crude elements that Orton would have polished to glistening perfection, and for all the outrageous fun, there are evident flaws in this final work.

You can read all about him in his diaries (prepare to have your hair stand on end with the salacious detail) and in the biography, Prick Up Your Ears by John Lahr. An easier way in is to watch the movie based on that book, also called Prick Up Your Ears (1987)*, with a screenplay by Alan Bennett and with Gary Oldman as Joe and Alfred Molina as Ken (and every British actor you’ve ever loved in supporting roles).

Our late friend, the actress Rosalind Knight, worked with Orton at the Wolsey Theatre in Ipswich. He was a shy, aspiring actor, still calling himself by his given name John. He confided in Rose that he was giving up acting and was going to write instead. A few years later, Rose’s flatmate Sheila Ballantine was appearing in a new play called Loot at the Jeanetta Cochrane Theatre, and told Rose, “The chap who wrote the play I’m in says he knows you.” A reunion was arranged, and Joe escorted Rose to a performance of Loot – and while she watched the play, he sat beside her and stared at her to see her reaction. I find it very touching that one of our major dramatists longed so much for reassurance in his early days.

I hope his reputation is now secure, and that his plays can be enjoyed on their own terms.

*Free to stream on ITVX, or pay on AmazonPrime.