27/06/24 Fredo writes –

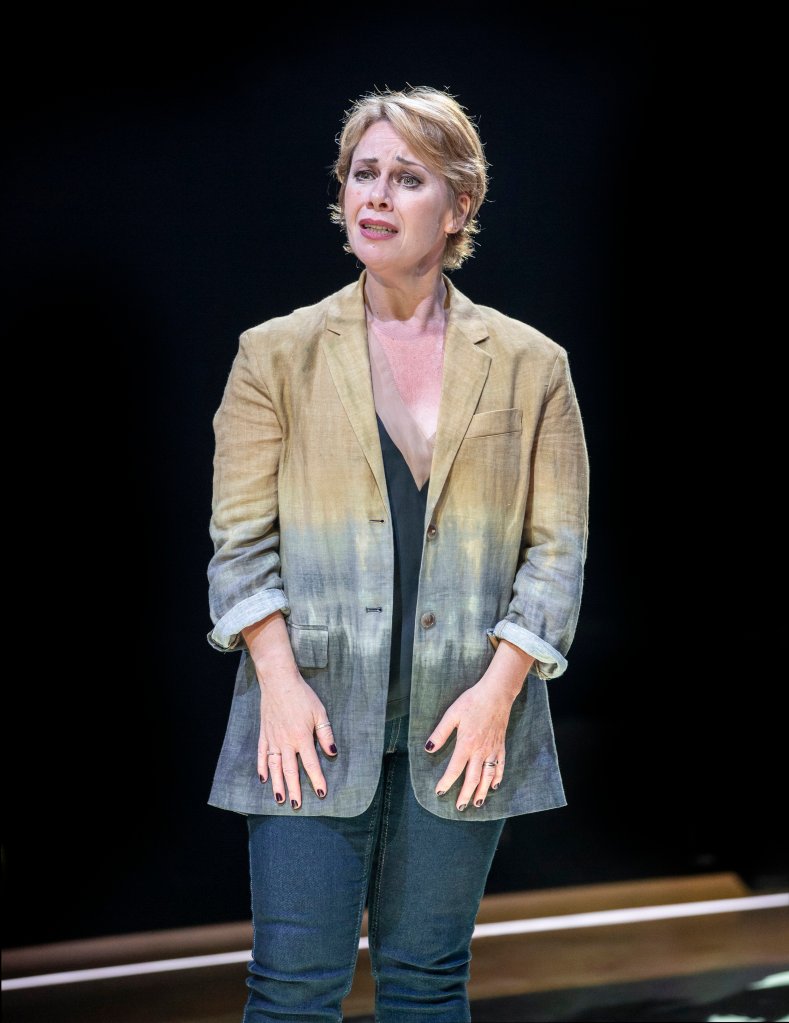

Alma Mater

By Kendall Feaver, at the Almeida

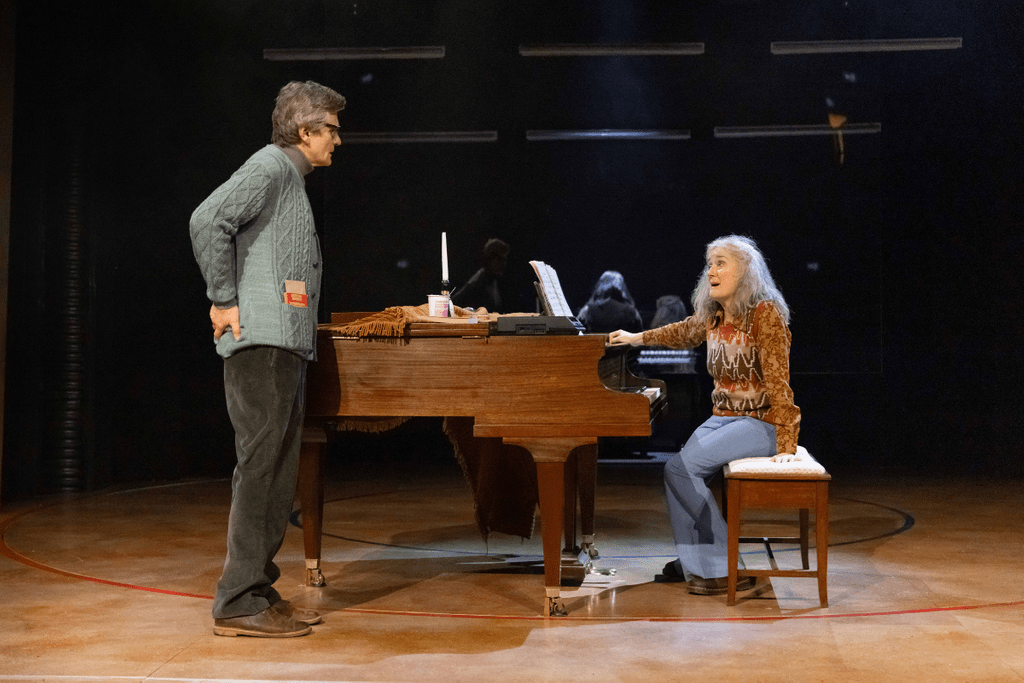

It’s a minefield. There’s certainly been sex, and alcohol was involved, and it’s a young female fresher’s first night at a formerly all-male college. There’s an allegation of rape, and soon positions are polarised behind barricades of sexual politics. Add a touch of racism into the mix, and watch as the storm develops to devastating proportions.

At the centre of it all is Jo, the first female Master of the College. A first generation feminist (but tellingly, retaining the title of her post), Jo struggles to deal with the situation fairly, and according to the college’s complaints protocol. Her efforts satisfy neither the victim and her supporter, nor her colleagues on the staff. It’s a seesaw ride as Australian playwright Kendall Feaver adds new perspectives, and deals a few wild cards from the bottom of the deck.

Despite some clunky exposition in the first act, the play improved as it went along – though there was perhaps one wild card too many in Act Two. Nevertheless, Feaver deals even-handedly with an inflammatory subject. There isn’t ever going to be a good outcome, but she ends the play well with advice any mother should give her daughter.

Except, oh no, it’s not the end: we return to clunky-mode for an unlikely, unnecessary and unconvincing final scene. Why, Kendall, why, when it was all going so well? And why didn’t director Polly Findlay intervene?

The actors play with commitment, especially Liv Hill, as the victim, and Phoebe Campbell as the activist friend who pulls her strings. The ever-reliable Natalie Armin is the voice of reason from the sidelines, until it appears that she too has skin in the game.

All the cast sit on the stage, so we are surprised by the late entrance of Susannah Wise, as the mother of the accused boy. This character effectively disturbs the direction in which the play seemed to be heading.

And who was the attractive man with the movie-star good looks, who came to the front of the stage as the play was about to begin? None other than the Artistic Director of the Almeida, Rupert Goold, bearing the news that Lia Williams had had to withdraw from the play because of ill health. They had had to cancel several performances, and the gifted Justine Mitchell had been parachuted in to take over. This was going to be her second performance, after two or three days rehearsal of a substantial role, and she had to read from the script.

We know that Justine Mitchell is a fine actress (she was perfect in Faith Healer at the Lyric, Hammersmith) and she was already reading the role with understanding and expression, but clearly had some way to go. It was occasionally difficult not to replay some of her lines in the distinctive voice of Lia Williams, at her most Paula Vennells-esque.

While Alma Mater falls somewhat short of the high bar set by David Mamet in Oleanna, it can hold its head high among other plays with a college setting. Cum Laude, but maybe not Magna.

Our rating: ★★★/ Group appeal: ★★★

15/06/24 Fredo writes –

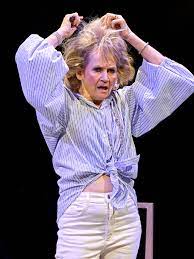

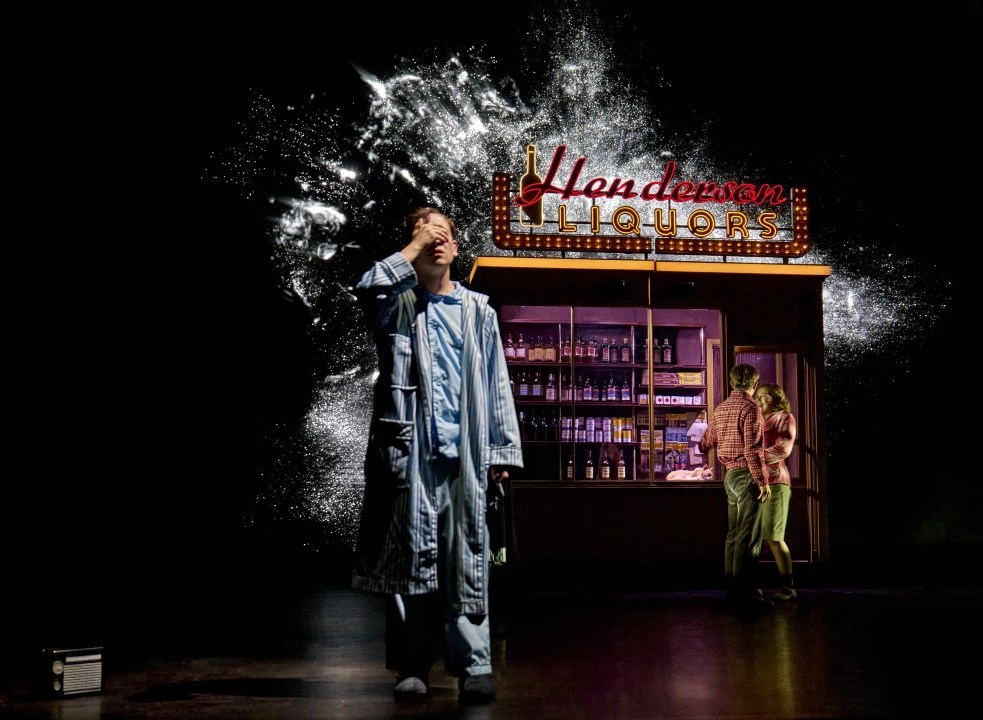

The Hills of California

By Jex Butterworth, at the Harold Pinter Theatre

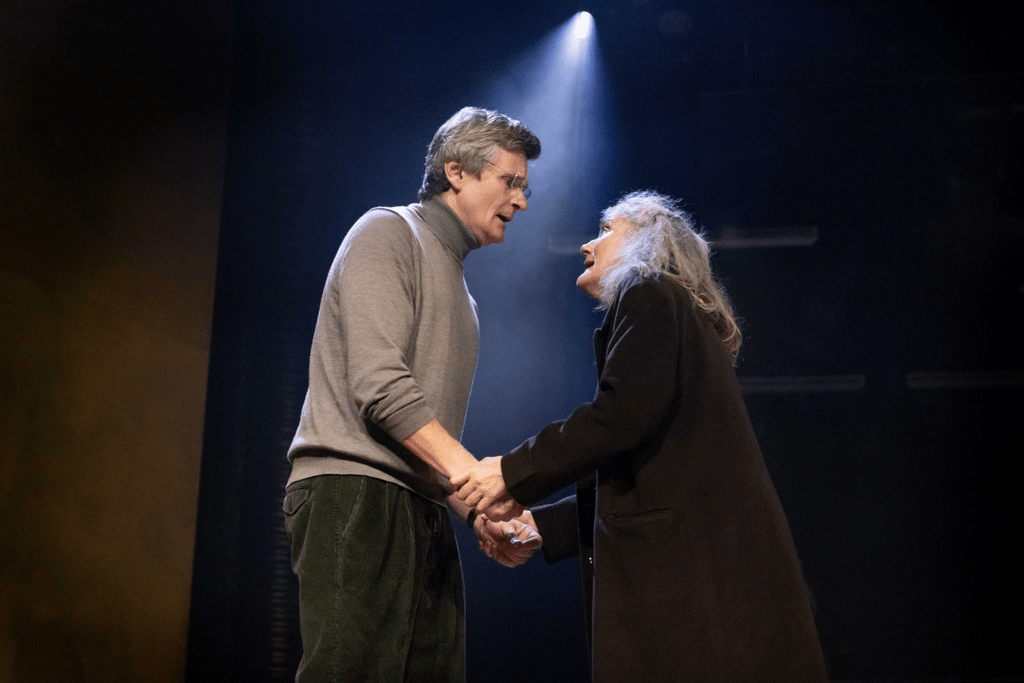

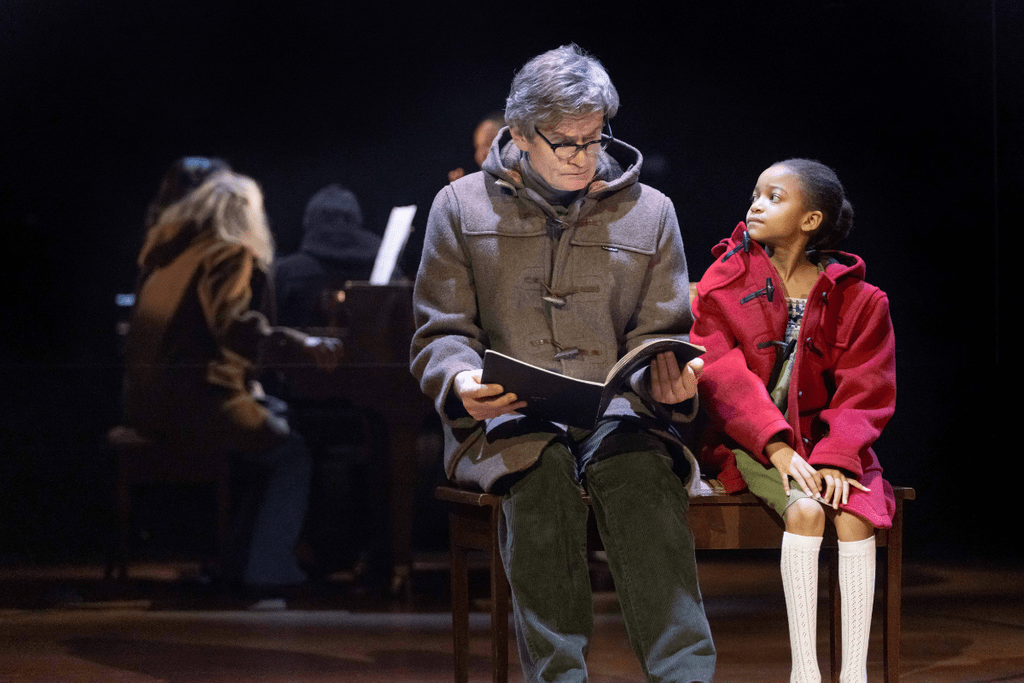

Here’s a winning formula: take three sisters, have an off-stage parent (dead or dying) and include much discussion about an absent relative who may or may not turn up.

Jez Butterworth has borrowed from Chekhov, The Memory of Water by Shelagh Stephenson, and Waiting for Godot, shaken them well, and the result is a sprawling family drama, The Hills of California.

We’re a long way from those hills. The play is set in Blackpool in 1976, the summer of the heatwave, in a cluttered boarding-house with vertiginous staircases (I hope the actors were paid danger money). As the sisters reunite to await the death of their mother (upstairs, off-stage), and recall their childhood, they reveal an affectionate yet fractious relationship, with opinions divided over their mother Veronica and the absent sister Joan.

The action goes back to the 1950s, and mother Veronica storms on stage in a firecracker performance from Laura Donnelly – I hadn’t suspected that Ms Donnelly had such a performance in her. She dominates her teenage daughters with her ambition to turn them into Blackpool’s answer to the Andrews Sisters. She bullies and cajoles her lodgers. She’s living on her wits, and ready to make any arrangement to make her dreams come true. It’s Gypsy, but without the showstoppers.

Butterworth is good at dialogue, and though he does tend to underline significant details, it’s his shafts of salty northern humour that makes it sing. All the cast handle it expertly, especially the sisters played by Leanne Best, Ophelia Lovibond and Helena Wilson. In the final act Laura Donnelly appears again as the missing Joan, still in command in a completely different characterisation. There’s support from the reliable Shaun Dooley and Bryan Dick as two ineffectual husbands, though they’re required to do little more than their usual Dooleying and Dickering. In fairness, they’re given a better crack of the whip in the flashbacks, as different characters. Corey Johnson has just one scene, as a visiting impresario, but he brings the stillness of suppressed menace and ruthlessness that disturbs the audience.

There’s a good choice of music to enjoy: Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy from Company B isgiven a production number by the young sisters, while It Never Entered My Mind and When I Fall in Love are used with a telling degree of irony.

But what is the play about? Are we to understand that while sisters are bad news, mothers are worse, and men are either Dooleys or Dicks? That the old times were tough, and look at the problems that they caused? Or that we’ve seen all our dreams disappear, but at least we were able to dream? It’s familiar territory. This is played out at extravagant length, and while I wasn’t bored, it crossed my mind that Butterworth may be the most indulged playwright of his generation. Both Jerusalem and The Ferryman had huge casts, and so does this one; I counted at least two characters who added nothing to the plot and hardly justified their brief appearances. I think the producers and director Sam Mendes might have demanded a tighter script from a less celebrated writer. (Mark Rylance was in the audience, scanning the play for a juicy role for later; there isn’t one).

Although the level of performance is consistent through to the final act, I thought that a certain slackness in both writing and direction was apparent here – for instance, there are many references to the sweltering heat, but Joan arrives swathed in a heavy coat. I wasn’t convinced by the easy resolution of the conflicts that the play had explored.

I didn’t not enjoy this play; in fact, I was entertained and engaged by most of it. I wanted something to bite down on, and though it has a tough nut in the middle, it was more soft-centred than I’d hoped for. But when the cast harmonised on Dream a Little Dream at the end, I almost gave in.

Our rating: ★★★/ Group appeal: Possibly ★★★★

Why didn’t we take a group? The ticket prices were high, and there wasn’t a group offer until much too late in the play’s run. Although the cast is very talented, there wasn’t a star name to lure audiences to the Stalls.

Photos: Mark Douet

03/06/24 Fredo writes –

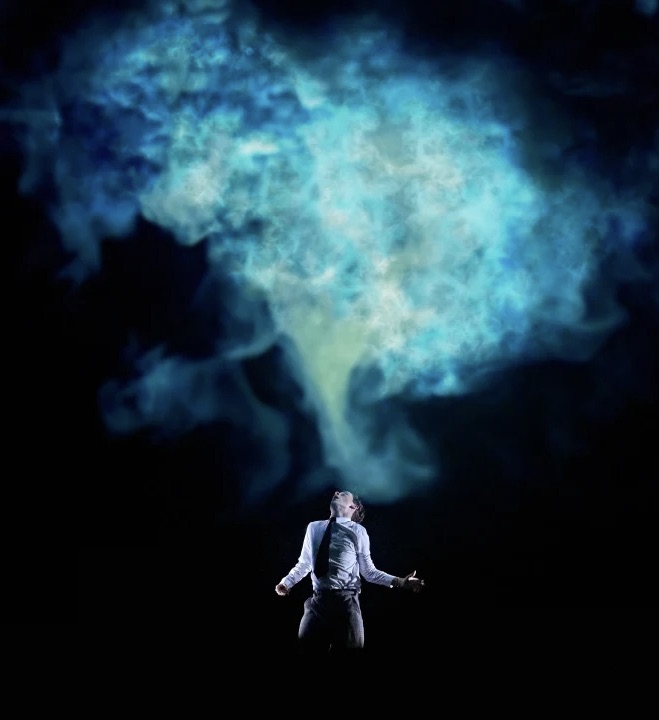

Between Riverside and Crazy

By Stephen Adly Guirgis, at Hampstead Theatre

Certain writers have a talent for writing titles. Stephen Adly Guirgis showed his hand with Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train and The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, and though I couldn’t tune in to those early works, I enjoyed a later play with another eye-catching title, The Motherfucker with the Hat. Hampstead Theatre admits that it lost its nerve over presenting that one, and left it to the National Theatre to pick up that hilarious comedy. Now Hampstead have realised their mistake, and are making amends with this one.

And they’ve gifted it with a towering performance from Danny Sapani, who holds the stage as Pops, who’s been invalided out of the NYPD and has a pending compensation claim against City Hall. He was shot while off duty by a white officer. While waiting for his life-changing settlement, he’s taken in his errant son and his girlfriend, and a recovering addict, to share his apartment. We can guess that this won’t end well.

It’s in the middle of the first act that the play suddenly explodes to life. Pops has a visit from his former NYPD partner Audrey (Judith Roddy) and her fiance (Daniel Lapaine) who try to persuade him to drop his claim and accept a settlement on his case. At this point, I sat back in admiration at Guirgis’s skill in building a scene, as Pops’s rage boiled over. It’s a great piece of writing. Full credit to director Michael Longhurst, who has form in orchestrating big scenes like this, and to Sapani’s fellow-actors for matching his performance.

Nothing that follows quite lives up to this, though the play continues to be involving and entertaining. There’s a delicious scene in Act Two when Pops is visited by a Church Lady, played with wry humour and faultless comic timing by Ayesha Antoine. There are further revelations and surprises, and Danny Sapani holds our interest in a firm grip.

I enjoyed the play very much, but I wouldn’t have guessed that it was a Pulizer Prize-winner (2015). The cast were excellent, but they had to work with a flat lighting design, and a cumbersome set – which eventually yielded the sort of coup de théâtre that Hampstead Theatre so loves.

Between 3 and 4 stars? I’ll go Crazy, and give it 4; one of those is for Danny Sapani.

Our rating: ★★★★/ Group appeal: ★★★½

After the play, we ran into the charming Ayesha Antoine at the box-office, and congratulated her. What is it like to to be on stage with a powerhouse like Danny Sapani? She laughed and agreed that though he is powerful, he’s also very playful. Nice to know.

01/06/24 Mike writes –

Bluets

Based on the book by Maggie Nelson, adapted for the stage by Margaret Perry, at the Royal Court Theatre

Bluets is based on “Maggie Nelson’s bestseller” and I wonder why the book sold so many copies. There seems to be a market for fictional tales of suffering (ie A Little Life). The play is a bestseller too having sold out at the BoxOffice, though I guess that may be due to the always-controversial director Katie Mitchell and the presence of Ben Whishaw in the cast. He was our draw.

I presume the narrator (and it is very much a fractured prose narrated rather than dramatised) is female, as is the book’s author, but here they are performed by a mixed-gender trio – Emma D’Arcy, Kayla Meikle and Ben Whishaw. They are meticulously well-drilled in the current stage fad of performing for a video camera with close-ups shown on screen. Part Theatre and part Cinema, I have invented a name for it – Cineatre (pronounce as you wish)!

It’s a complex set up – three video cameras focus on three lectern/tables each with a bottle of Maker’s Mark Whisky; the three actors manoeuvre small items into view as they share sentences democratically among themselves. They pose against three screens providing video backgrounds of diverse streets, clouds, a swimming pool, a hospital, a bed, etc etc. Those three story-tellers have to continually change costumes, though in-shot we never see more than close-ups of their head and shoulders.

Photos: Camilla Greenwell

It is all shown on a cinema-size screen above the stage with stagehands bringing on props to appear in the multitude of movie clips. It’s a fascinating exercise in Cineatre technique, but after a short while tedium takes over.

The first-person writing concerns an overwhelming love, not for a person but for a colour, blue. The obsessive collects ephemera – rings, stones, wrappers, fabrics, bluebags, everything blue – and they suffer in their relationships, their friendships, their mental health. Should we care? It seems some audiences and readers do. I remained focused on the performers going through their paces and never for a moment did my thought or emotion touch on this triple-split persona.

Some of the audience loved it, those who earnestly devour a feminist flavour laced with breakup, paraplegia, sex, depression and obsession, those who stood and cheered after the longest 80 minutes in my memory. No way me too! Without hesitation I could rate this one star, but with a pause for further thought I will add another for the efforts of the cast and production team. Now we await what Katie will do next.

Our rating: ★★ / Group appeal: ★

07/05/24 John R writes –

Machinal

By Sophie Treadwell, at the Old Vic

I saw this stupendous production at a Saturday matinee with Mike, Fredo and our famous critic Garth. It’s a play written in 1928 by American writer Sophie Treadwell, a journalist inspired by the trial of Ruth Snyder and her lover Henry Hudd Gray for the murder of Ruth’s husband Albert in 1927.

The play anonymises characters; Ruth is Young Woman, Albert becomes Husband etc. The first scene is set in a cramped and triangle-shaped office space with mustard-coloured walls and windows that only open onto other mustard coloured walls. Doors are flush with the walls so the large stage is made to feel small and threatening. The cacophony of office life is shown by a tightly clustered crowd containing Telephone Woman, shouting greetings and keeping her eye on the room, while the office drudges, moving in synchronised clumps, tell us that Ruth is in trouble for being repeatedly late.

We then see her at home with her awful mother (Buffy Davis) obviously on a syndrome of some sort. In a fierce series of scenes we see her marry her boring and uncomprehending boss, the agonising birth of her child, her post-natal depression, and a long scene with a handsome stranger picked up in a dubious bar (where other sexual transactions are being fixed) which offers her the chance of escape from her marriage. This hopeful relationship doesn’t transpire. She plans to murder the Husband, is found guilty and sentenced to death in the electric chair. In the 1993 production at the National Theatre, Fiona Shaw played the lead and it showed her actual execution – in this production a crowd of men huddle around her in the chair, backs to the audience, then someone clicks the huge switch.

This production shows director Richard Jones at his brilliant best. It is an expressionist play and the visual elements, the lighting, the sound effects, are marshalled into a tightly knit nightmare. Rosie Sheehy gives a stunningly brave performance, coping with torrents of thoughts and feelings, and a physical bravery that shows her fight to battle the hazards of Life heaped upon her. The automated movement of the crowds and the visual inventiveness makes this play a tour de force. Most of the cast play several (anonymous) roles (lawyer, jailer, reporter, judge etc) but both Tim Frances as the Husband, Pierro Niel-Mee as the Young Man, Buffy Davis as the Mother, manage to imprint their individual characters onto a frenetic background. In addition to Richard Jones, special admiration must be given to Sarah Fahie (movement), Hyemi Shin (Set), Benjamin Grant (sound), Silverman (Lighting) and Nicky Gillibrand (Costume).

Our rating : ★★★★★

Group Appeal ★★★ (those brave enough

would probably give it 5 stars as well)

Photos by Manuel Harlan

24/04/24 Fredo writes –

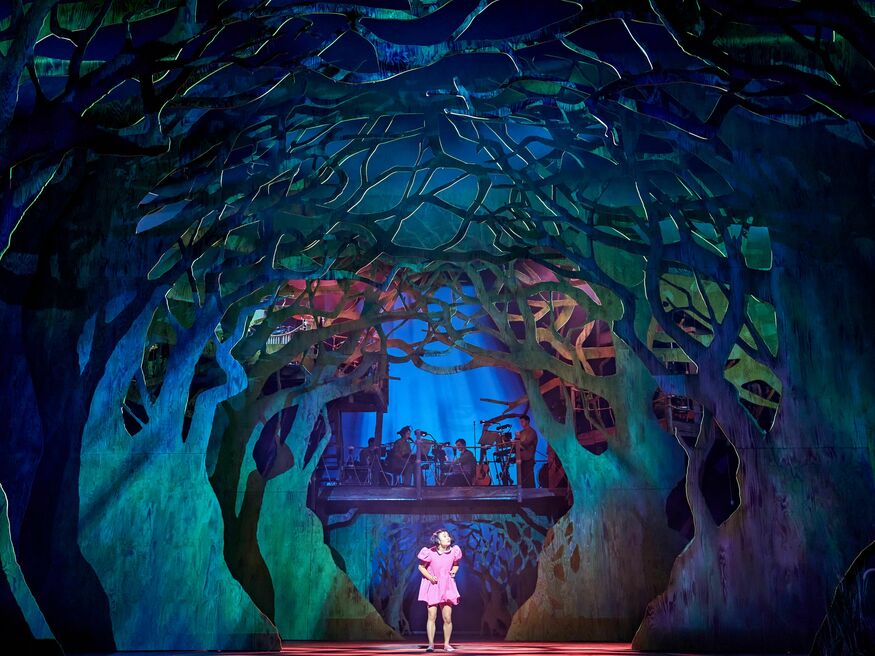

London Tide

Based on Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend, adapted by Ben Power with songs by PJ Harvey and Ben Power

When I’m asked, “What’s the best book you’ve ever read?” I always reply “Bleak House by Charles Dickens.” It has everything: drama, humour, a detective story, multiple characters, sub-plots, and the two best death scenes in the English novel. The death of Jo is a heart-rending set-piece, and the death of Krook is, well, “bizarre” doesn’t come close; you have to read it.

I wish my enthusiasm extended to his last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, but here the writer is a victim of his stylistic mannerisms. He doesn’t fill his tale with characters but with collections of characteristics.

I hoped that the best way to reconsider this work (and it is regarded by many as a masterpiece) was to see the adaptation at the National Theatre.

It starts well enough, with the cast of 20 clambering out of the pit onto the stage, and we’re quickly introduced to the major characters. And then…

…and then it slows down. The complicated plot has to be set out, and this leaves little time for the development of any themes. There are too many characters to fit into this slimmed-down version, even at a generous length of 3 hours and 15 minutes.

In Our Mutual Friend, Dickens takes a vertical slice of Victorian society and exposes corruption at every level. The brutality of the river-front and financial venality of the city are intertwined, and all are connected by the river Thames flowing through the city. Despite the large cast, many of the characters who add substance as well as colour to the novel are discarded, which led me to wonder in the second act why they had bothered at all, if they had to leave so much out. There is little of Dickens’s social concern and satire. I expected at a time when the Thames is as polluted as it was in the 19th century and when the political scene is as confused, some parallels would be drawn. Instead, we have a late-in-the-day feminist twist, which is at odds with the rest of the story.

It wasn’t helped either by the dirge-like songs that interrupt the action. These seem designed to create a mood, and don’t let anyone try to persuade you that this is a musical, as they are neither character- nor action-driven. There is very little set, and the vast Lyttelton stage seemed empty, especially when director Ian Rickson chose to position the actors at the extreme sides of the stage. The lighting by Jack Knowles was spectacular.

Actually, I enjoyed it slightly more than this review suggests, and the audience liked it. We met a neighbour there, and she was enthusiastic at the end.

Photos: Marc Brenner

All credit to the actors, especially Joe Armstrong, Tom Mothersdale, Jamael Westman and Peter Wight, who must have hoped for better material. Jake Wood was under-employed.

Perhaps I should have stayed at home and started reading the book again.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

23/04/24 Fredo writes –

The Comeuppance

By Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, at the Almeida Theatre

There’s a tradition in American drama of Porch Plays – plays that take place in the garden and back-porch of (usually) a middle-class home. It’s a convenient location as characters can come and go, disappearing into the house to cook dinner, or find an important letter. Neighbours call by, carrying pie, and everyone is friendly and on good terms. Writers like William Inge and Arthur Miller used this format subversively in plays such as Picnic and All My Sons. And here comes Brandon Jacobs Jenkins with a new twist.

There’s a sign that Jenkins has ambitions beyond a homey domestic drama. There’s a Stars and Stripes hanging by the side of the stage; could this be a state of the nation play, by any chance? Soon references to post-Columbine, post-9/11, post-Afghanistan and post-6 January indicate that his characters have a lot of history in common. Not just national history; this is a reunion play, and we know that that won’t end well. It’s twenty years since they were in high school, and 15 years since they all have been together – they all are a little frayed round the edges. There will be ancient hostilities coming to the surface as earlier relationships are examined and re-evaluated; there will be lies exposed, and tears and recriminations before the night ends, . As Emilio sums it up, “It’s the age of bad decisions turning into consequences.”

But what else is going on here? The play opens with one of the actors in a spotlight, addressing the audience, and it’s hard to catch what he’s saying as his voice is echoed by a playback track. And at the moment he reveals that he is Death, the stage lights come up and he’s a different character altogether. As the play progresses, every character gets their moment in the spotlight, and weirdly, the actors abandon their American accents for their own voices. The distortion in sound is disorientating.

I didn’t understand this distancing technique. I regretted that Jenkins and director Eric Ting employed it as the play it interrupts is both interesting and very entertaining. Jenkins can write sparky dialogue, and even if the actors play it a tad fast (I’d have liked more time to catch all the zingers) they all deliver with full-blooded performances. Anthony Welsh carries most of the action, and he’s well supported by Yolanda Kettle, Tamara Lawrence, Katie Leung and Ferdinand Kingsley. I wish I’d listened more closely to the earlier part of the play, when characters who were yet to appear were discussed.

Photos: MarcBrenner

There’s a lot to take on board, and that’s not a complaint. I feel this play repays attention and reflection. I’ve enjoyed Jenkins’s other plays – Gloria at Hampstead, and Appropriate at the Donmar (but I’d rather forget An Octoroon at the National) and I’ll be interested to see what he does next.

I’d have been happy to give it 4 stars, but I’m afraid that the distancing device confused me, so it gets a respectable 3.5.

Our rating: ★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★

22/04/24 Fredo writes –

Charlotte Kennedy & Jordan Lee Davies

in: Honestly, we’re fine!

Cabaret at The Crazy Coqs.

“Well, that went well!” laughed Jordan Lee Davies to his friend and co-star Charlotte Kennedy, when they finished their opening number. We all laughed as well, as he had gone wrong on the tricky lyric of You’re the Top, causing her to depart slightly from Cole Porter’s words. Did it matter? Not a bit: they’re assured performers, and they were playing to an audience with a huge number of family and friends, as well as more objective observers like ourselves and our hosts, Jan and Michael. Charlotte and Jordan confessed that despite the title, they were far from fine. He was dosed up on codeine to relieve back pain, and she had been to Harley St that morning and had a test patch sellotaped to her back, which impaired her movement. If they hadn’t told us, we’d never have guessed, as they were in an ebullient mood. Charlotte looked ravishing in her sequined mini-dress, while Jordan admitted that he looked like he was going to a lesbian camping convention!

They had reason to be cheerful. They sang I Have Confidence in Me, one of Richard Rodgers’s solo compositions for the movie of The Sound of Music, which demonstrated that they combine the wide-range of their voices with assured performance skills. In fact, Jordan might plead guilty to the charge of occasional brashness, but he revealed a more gentle side of his talent in his solo Song on the Sand from La Cage aux Folles (he understudied the role of ZaZa at Regent’s Park last year).

Charlotte’s voice is supple, as she demonstrated with Miss Bird (from Closer Than Ever); she said she related to this character because of the amount of time she spent temping between acting jobs. This difficult song was only a warm-up act for a later show-stopper, when she allowed her voice to soar on Love Never Dies. She sang higher and higher, and may even have sung notes that could only be heard by dogs in the neighbourhood. She brought the house down.

The programme included three songs by Stephen Sondheim – a solo for Jordan with A Moment in the Woods from Into The Woods; a duet with Charlotte of Unworthy of Your Love from Assassins; and You Could Drive a Person Crazy, a trio from Company (with help from their talented accompanist). They were all a masterclass in interpretation.

It was a great evening. Yes, it would be difficult to give a bad review to a performer when his gym-muscled father tells you afterwards how proud he is, but there was never a chance of that. There were occasional quips and puns which we missed, but the rest of the audience was quick on the uptake, and there was so much to enjoy that it didn’t matter.

Show business is a tough world. Here are two young performers with talent and personality to spare. Charlotte played Eliza in the UK and Ireland tour of My Fair Lady last year, but is now back to temping again. She’s had one audition this year. They are both veterans of Les Miserables. Jordan was a finalist on The Voice – you can check him out on YouTube. Yet here they are, creating their own show and looking for a job where they can use their talent and training.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

20/04/24 Mike writes –

The Ballad of Hattie and James

By Samuel Adamson, at the Kiln Theatre

As the song goes, “I know a fine way to treat a Steinway”, but here we have two rivals forever trapped in a not-so-fine conflict on a Bechstein.

We are introduced to Hattie as she plays on the public piano at St Pancras Station (2024, this week!) then old friend Henry passes by. It’s time to flashback to their teenage meeting (in 1976) at school and learn about their rival attempts over many years to achieve success with their separate musical vocations. The road to fame, or not, is far from straight. Tragedy hits the duo; there’s a dispute over music composition; a developing fondness for each other is disrupted by gay uncertainties; and family history and inheritance add an extra complexity to an already meandering and jumpy narrative.

A grand piano on a simple revolving stage is the main prop, so the weight of this saga rests heavily on the two main players, Sophie Thompson and Charles Edwards. Other adult roles are filled by Suzette Llewellyn, and a pianist slips seamlessly into the piano-playing for our titular duo.

Thompson’s natural zany persona contrasts with Edwards’s more grounded personality. I can understand this casting could work in theory but on stage here, with convincing age changes essential, it does not. As an old and stooped woman (with long grey hair) Thompson convinces but as an animated swearing teen (still with long grey hair) she does not, and her ages between continually jar. Edwards changes jackets and body language far more persuasively from age to age, back and forth. Yes, the decades change abruptly, from past to future and back, of which we are thankfully notified by backdrop projections.

Samuel Adamson has written several well received Off-West-End plays and adaptations given starry casts over the years, and here we are again with another. But the overriding problem with this one is the far from clear direction that the storytelling takes. Miss a word and we miss a vital plot point. Miss a date-check and the two entwined careers are left floundering. It all might work better on page than stage. It’s not easy for the players to convince us and not easy for us to care about their histories – he excels, she is overlooked, and of course it’s a gender thing. While Edwards keeps a steadfast grip on his role as James and holds our sympathy, Thompson irritates with her caricatured portrayal, and distances us from the enigma which is Hattie. This is particularly unfortunate – when she briefly has to play Hattie’s daughter in Act Two, she plays with a natural demeanour otherwise sadly missing.

I had assumed this performance was a preview so changes could be made, but not so – Press Night had been the day before. Our companion left at the Interval, befuddled and bored. I cannot say we were bored because our main reason for attending was to see these two actors together, but the Ballad certainly still needs a retune, an edit and copious director’s notes. The audience were enthusiastic, but maybe they were influenced by good reviews.

Our rating: ★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★

12/04/24 Mike writes –

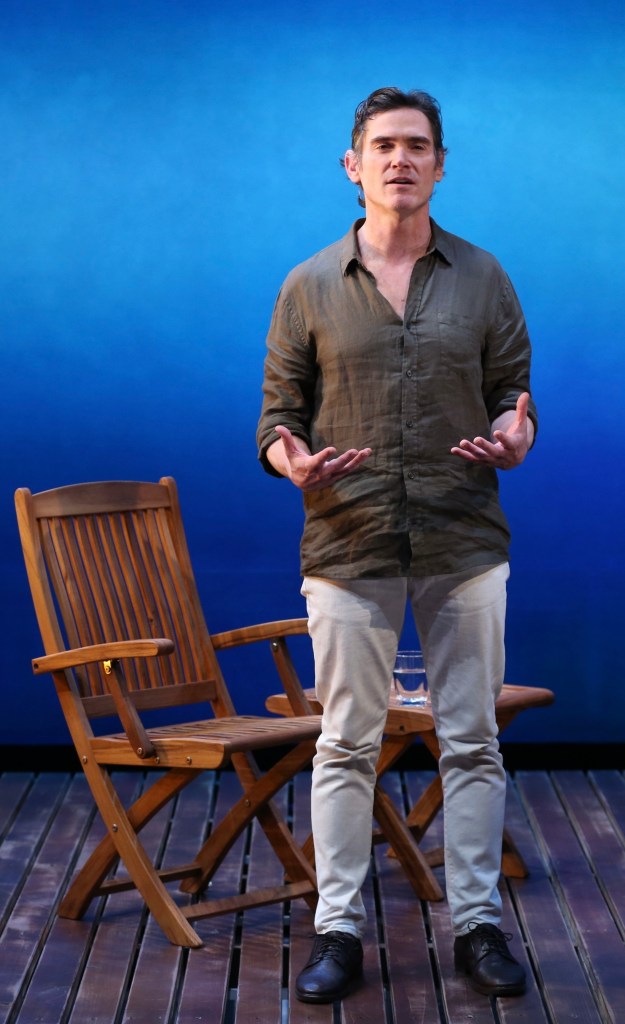

Harry Clarke

By David Cale, at the Ambassadors Theatre

Photos: Carol Rosegg

Note: If you watched the second series of tv’s The Traitors, the winner, who deceived all his fellow contestants, is called Harry Clark. Coincidence? Or not?

Billy Crudup is Harry Clarke, proclaims the ad. Yes, but he’s more than that. Crudup is firstly the very American Philip Brugglestein then later Philip’s alter ego, the very British and very Cockney Harry Clarke of the title. But this multi populated monologue goes much further.

Disconcertingly, Crudup begins in full verbal torrent as a fey Indiana country-boy aged eight, with an ability to master a posh English accent and irritate his working class parents beyond endurance. Then, as a closeted young gay man in New York, he discovers an assumed laddish accent can be a useful guise to escape into a butch persona so unlike his real self. Philip becomes the Londoner Harry.

Now, as Harry, he inveigles himself into the life of Mark, a rich and boorish divorced Rode Island man and his family; it’s a bonus-bringing role for Philip to play. And a bonus for us too, as Crudup takes on all the voices of the assorted characters Harry is introduced to. These include Mark’s obsequious big-haired mother Ruth, and Stephanie his lascivious sister beguiled by this supposed sexy beast from across the pond. The fictitious persona Harry invents for himself leads him down an ever steeper path to what could easily be fate or fortune.

The enthusiasm with which Crudup enriches his story-telling easily seduces his audience into rapt attention when we’re not guffawing with delight at how he skewers a variety of social types, male and female. There’s a sexual ambiguity as well as a class diversity among these people which adds an extra frisson of surprise to this animated performance. The bedtime scene set on board a luxury yacht has eye-watering tension. It’s all a gripping and hilarious telling of a shaggy dog story, an unpredictable roller-coaster of a ride, featuring more than a dozen bizarre personalities with Harry at the centre. It’s an intense performance which holds our attention completely as Harry’s bogus lifeline balances on the edge of discovery.

Crudup is brave to bring the show from Broadway to London where we might be more critical of his various British accents, but of course it’s Philip not Billy who is putting on the UK accent to impress his US friends. Alone on stage for 80 minutes with a barely used table and chair, Crudup has only a few subtle lighting changes to support him, but we hang on his every word. Switching so continually from one accent to another is certainly impressive. He is never himself, always the voices and mannerisms of the many characters his storytelling brings to us. Only at curtain-call do we see him relax back into his real self.

Not all the reviewers have been won over by this amusing display of contrived narrative contortions, but we certainly were. The audience whooped with delight; it’s a tall tale I recommend unreservedly.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

11/04/24 Jennifer writes –

The Devine Mrs S

By April de Angelis, at the Hampstead Theatre

A new play about Sarah Siddons, considered the greatest tragic actress of her age, starring the lovely Rachael Stirling was worth travelling all the way to the Hampstead Theatre to see. The play was written by April de Angelis who has produced other works of note. However, on this occasion, it’s a shame to say she missed the mark despite the interesting premise of the play. Maybe this was because of a desire to pack too much of her own modern perspective into the story she was aiming to tell and a lack of discipline from the play’s director, Anna Mackmin.

During the play, we learn that, in common with most women of her age, Siddons had very limited control over her working life or her finances. These were managed by her philandering husband and her brother, John Philip Kemble, a less successful actor and the manager of the Drury Lane Theatre where many productions starring Siddons were staged. de Angelis presents Siddons’ lack of agency through a modern lens (including current swear words) and, while we sympathise with her impotent rage at how she’s treated it somehow doesn’t ring true in the context of the times. We also learn that Siddons played Hamlet in Dublin (one of nine times during her stage career) but the focus on this part of her life in the play is a strange sequence with a priapic fencing master which perhaps is meant to be funny but somehow fell flat.

Rachael Stirling does her very best with a difficult script supported by a small cast playing multiple roles which are sometimes difficult to distinguish. To add to our confusion there are several sub plots including the story of a female playwright whose work Siddons is unable to get on stage (interesting), a gentlewoman committed to a madhouse by her husband whom Siddons tries to help (over complicated) and the attempted ravishing of Siddons’s maid by her brother (treated as an 18th century me too moment). Elsewhere, Dominic Rowan hams it up as Kemble and, I’ll admit, sometimes I was glad of the light relief of some straightforward comedy amongst the meta contextualising of the fight to dismantle the patriarchy (not quite a quote from the text but almost….).

In conclusion, two stars for the production with an extra star added for Stirling’s performance and charisma and Lez Brotherton’s evocative set. If a lesser actress had played the lead role I might have left at the interval as the people in the seats next to me did. However, my main reaction to the play is one of sadness at a missed opportunity to tell us more about an interesting female character from theatrical history.

Our rating: ★★+★/ Group appeal: ★★★

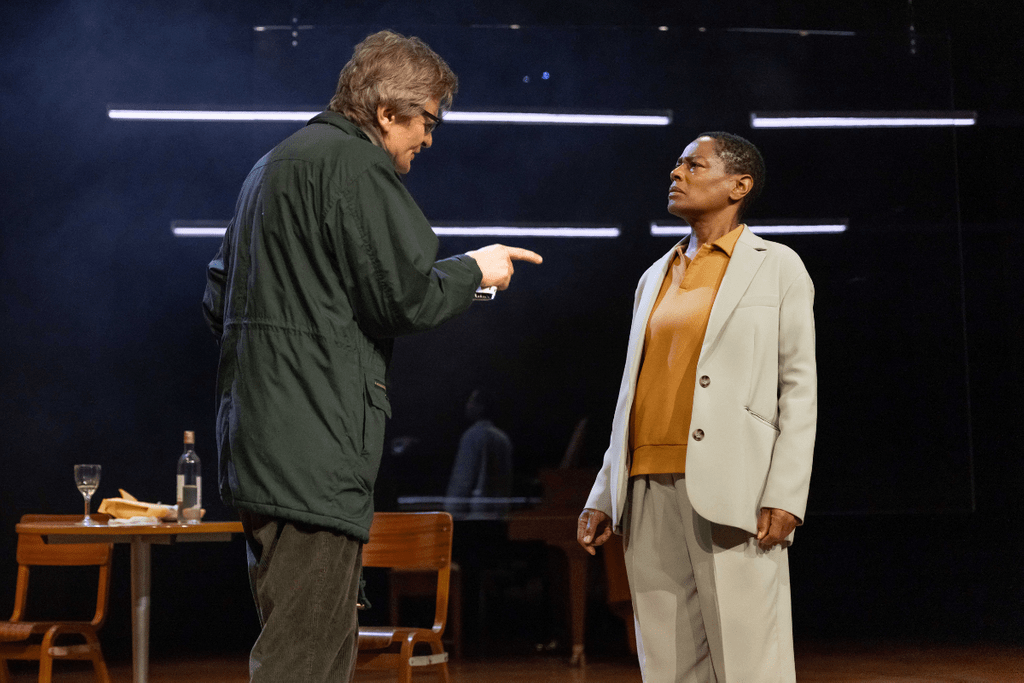

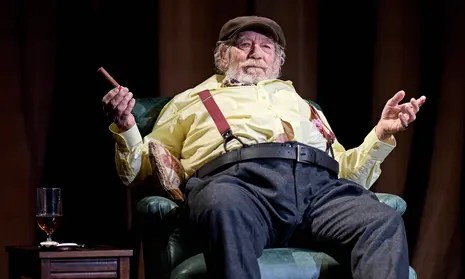

10/04/24 Fredo writes –

Player Kings

Adapted by Robert Icke from Henry lV Parts 1 & 2 by William Shakespeare, at the Noel Coward Theatre

No, it wasn’t an oversight. I hadn’t booked to see Ian McKellen in Player Kings because I really didn’t want to see it. Henry lV Part One was one of my set books at school, and I had to study it for far too long. I’d written essays and said all there was to say about it. When Mike raised the subject, I airily waved the suggestion away.

Then we were invited to see it by Delfont Mackintosh, and well, it would have been rude to refuse. For the second time in a week, we walked up St Martin’s Lane to see a play that lasts more than three and a half hours!

In his long career, Ian McKellen hadn’t played Falstaff before, and it’s possibly one of the few major Shakespearean roles that he hadn’t tackled. Now aged 84, and undoubtedly one of the great actors of our age, it would surely be worth seeing him in this role.

And he didn’t disappoint – as you’d expect, his Falstaff is a fully realised figure, with the weariness of age in conflict with a man living on his wits, who has a sense that his time is running out. He dominated every scene he was in, and his long, final exit was a masterclass in how to hold your audience even as you walk away from them.

Unfortunately for me, I find the scenes that Falstaff appears in to be the most long-drawn out and irritating part of the play. It’s a historical drama, and Shakespeare’s recounting of the political machinations is clear and tense, and far more interesting than the tedious tavern tales he indulges in with Falstaff. Yes, I know this character is said to embody the roguish qualities of the English character, but it’s all these elements that I dislike intensely: he’s a drunk, a cheat and and a scoundrel. By the time we got to the elegiac Gloucestershire scenes in Part 2, my patience was wearing thin.

The low-life scenes in the play drag, and it’s not the fault of the actors, as these scenes are no less strongly cast than the rest of the play (there’s a fair amount of doubling up). Rising star Toheeb Jimoh exposes the ruthless side of Prince Hal, and Richard Coyle is an unexpectedly aged and stern king. Samuel Edward-Cook as Hotspur brings some fire to his scenes.

I’d worried that Robert Icke might inflict his signature flourishes on this presentation, but he was very respectful to the plays. We both felt that the songs were an intrusion – there’s a black-clad counter-tenor who stalks the action in a fairly sinister and distracting way. When King Henry is told that he is being taken to die in a hospice called Jerusalem, we are treated to a totally unprovoked and irrelevant counter-tenor rendering of the hymn of that name.

Was I glad I went? Yes, very much so. McKellen had demonstrated in Frank and Percy just how much he can do with very little – a sideways glance here, a small gesture there – and here he took control and made Falstaff the centre of the action, with broader stokes and bolder colours. It was a good account of the play, and if I had to sit through it again, this was the best way to see it.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

09/04/24 Mike writes –

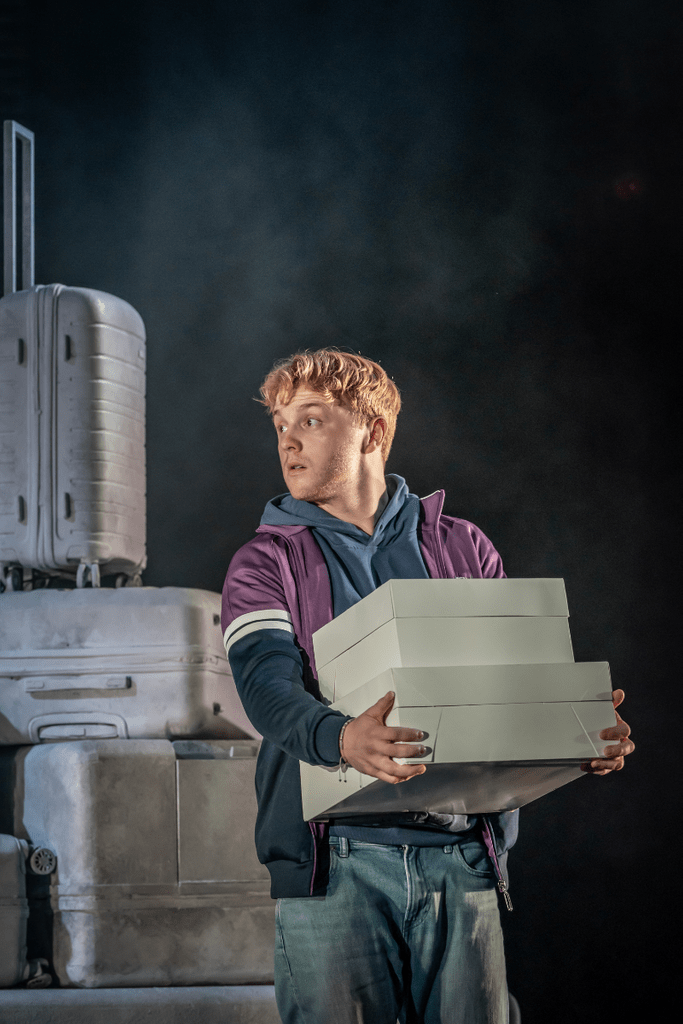

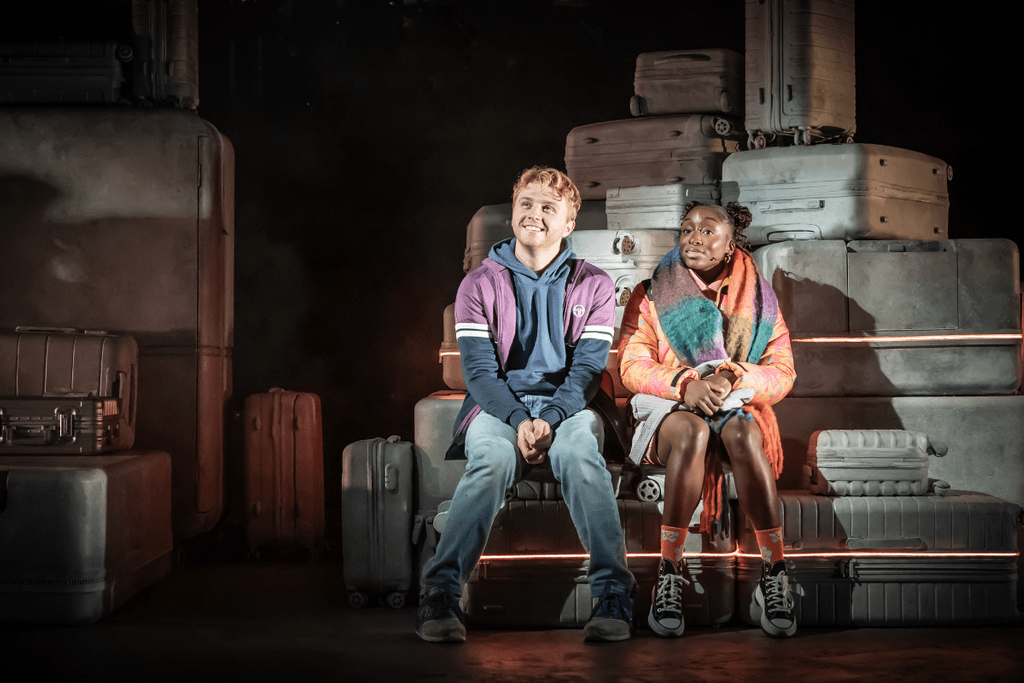

Two Strangers (carry a cake across New York)

By Jim Barne & Kit Buchan

What do you expect from a “musical”? Well, entertainment of some sort, of course. But what does the word bring to your mind? I read an on-line complaint recently (not yours!) that “It’s irresponsible to mislead. Plays with music which have serious themes should not be marketed as musicals. It’s a form of fraud.” I would say that’s nonsense. I wonder which show had disappointed the writer – Standing at the Sky’s Edge, Opening Night, maybe – both serious, no tap-dancing or glitter, but to my mind musicals can certainly have serious themes, and treatments can differ widely.

And so, you may wonder how serious is ‘Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York)’. The title is mundane enough to make you wonder just how serious, or not, it might be. The answer could go either way but, knowing it’s a musical when we were invited, we were keen to find out. This small scale show had opened at the Kiln Theatre but has now transferred to the West End and is packin’ ‘em in. We felt old (nothing unusual) as everyone else seemed to be Millennials, including the cast of two.

Dougal (Sam Tutty) has come to NY to meet his estranged father for the first time. Dad is marrying again having deserted mother before the birth of his child. Robin (Dujonna Gift) who is sister of the new young bride has come to meet Dougal at the airport and carry that cake to the reception. Meeting a never-before-seen father is certainly serious, with problems and emotions ahead. The stage is piled high with two revolving stacks of suitcases, each ingeniously opening up to form props. The backdrop is of course New York. Let the music begin. And the surprises.

Here we have the most upbeat, funny, emotional and tuneful show in town. Our two young leads have personalities to charm and amuse us. The script and lyrics plant humour right on target, focused on the characters of its contrasting duo – he, upbeat laddish from Crawley, a movie fan but innocent of life, full of energy and self-deprecating humour; she, hesitant, wry, scornful and abrasive with a very New York state of mind. They scratch each other’s wary face-on-the-world and slowly bond, not unexpectedly but certainly in the most winning and humorous of ways. The songs are full of sadness, joy and worldly-wise enthusiasm. We make friends with these two strangers. It’s a cliche but Yes, we really do laugh, cry and cheer them on.

It’s slightly serious, a little Sondheimy, character-lead, no dancing nor videos….and I would say it’s currently the best musical in town. Seriously.

Our rating: ★★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

04/04/24 Mike writes –

For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy

By Ryan Calais Cameron, now at the Garrick Theatre after the Diorama, Royal Court and Apollo theatres.

We are greeted by a dense haze, red floodlights and pounding rap as we enter the auditorium. Is this a party or, given the title, a requiem? A bit of both I think, but presented with a lively humour, a lexicon of attitude, touching insights, and energetic choreographed movement. These six black boys are diverse characters, eager to tell us about their lives, their enthusiasms and concerns, the pluses and minuses of being black. It’s a lively and uplifting group therapy session, with confessions and suppressed social problems given an outing, with us being allowed in for a confidential briefing.

Damed if you do and damned if you don’t is the message. There is pressure, to be proud of black culture but try to act white – it’s the Oreo influence to be black on the outside but white in the centre. It begins in infancy when toddlers learn they are different, then the pressures build, to assimilate or to be fought. All this is told in stories of life’s challenges, recognised by a perhaps 80% black and mostly young audience who respond enthusiastically with laughter and cheers.

It is fun, it is sad, and soon we both like and understand these boys, not so different to white boys but with an extra layer of growing-up problems to contend with. And with extra gender pressures to conform to a black stereotype normality.

After infancy, we are taken through the teen years, romance, sex, competition, aggression, the whole gamut with a lightness to entertain us but with a seriousness to interest us and to make us care. Only in the last half hour does the message begin to slacken its grip, unfortunately at the time when knife crime is added to the index. But even then the agile presentation with music, lyrical expression and a direct likability wins the day.

Way back in 1974 there was an American show by Ntozake Shange entitled ‘for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf’. It first appeared in Berkeley, California, and eventually transferred to Broadway where it won three Tony Awards and was revived there in 2022. It was described as a choreopoem, meaning poems choreographed to music. I believe it briefly came to London, perhaps to the Royalty theatre if I remember correctly, though Wikipedia suggests the Donmar before Sam Mendes took it over. At that time it appealed to a fringe audience, attracted by the strange title and even the subject. Now 50 years on, not before time, it’s the boys’ turn to tell their stories in similar fashion.

Times have changed and Black Boys now attracts a diverse audience which fills the West End theatre, black women being the most vocally responsive – those Boys are certainly appealing as they reveal their worries and weaknesses with a mix of bravado and charm. It’s good to find such black talent appropriately cast in a show that attracts a black audience without the patronising indignity of colourblind casting.

As an oldie in the midst of a mainly young, demonstrative, and packed audience, I missed a lot of the quips, punchlines and casual patois. But I still got the message and enjoyed the show. And a slick show it certainly is, never a preachy gripe. The old complaint of ‘white shows for the white elite’ is well redressed here.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

30/03/24 Fredo writes –

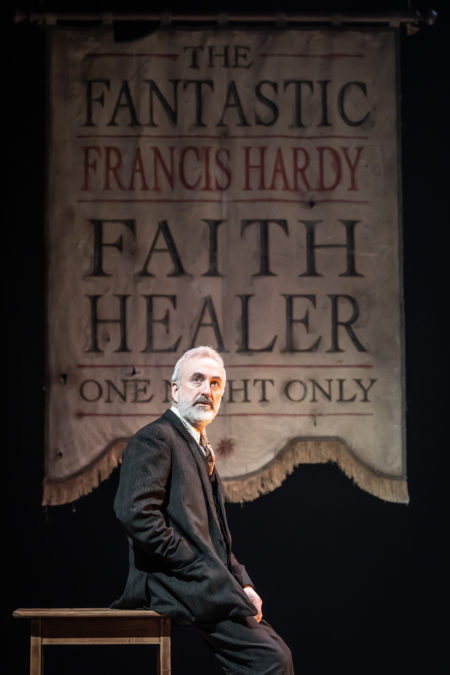

Faith Healer

By Brian Friel, at the Lyric, Hammersmith

It starts with an incantation, and there’s a nativity, and a martyrdom. There is little consolation in Brian’s Friel’s great play, until a possible moment of redemption at the end. The incantation is the list of the decaying villages in Scotland and Wales that act as stations of the cross on the Via Dolorosa followed by Frank, the self-styled travelling faith healer, with his wife Grace and his manager Teddy. It could be a road to self-discovery but, in the end, they all cherish at least part of their delusions as they examine and relive the trauma of their lives.

It’s a play that requires actors who are not just at the top of their game, but who also have a sense of wizardry in their performances. Director Rachel O’Riordan has gifted the play with three magicians. Nick Holder may well give the definitive performance of Teddy who is wildly out of his depth but trying to make sense of his part in this tragedy; Justine Mitchell, clinging to the last shreds of her sanity as she copes with the many traumas of her itinerant life, has never been better in her impeccable career. But the play rests on the shoulders of the Faith Healer, and here Declan Conlon conveys both the arrogance and self-doubt of his possible gift, and the heedless cruelty with which he treats his disciples.

However, the chief miracle-worker is Brian Friel. His assured narrative skill never falters; on each occasion I have seen this play, I’ve been aware of the audience breathlessly succumbing to the story-telling. It’s a masterpiece of construction. Most of all, listen to the language. Each character choses their words carefully and sets them like a diamond in the rosary of their sorrowful mysteries. It’s as though Friel performs an act of transubstantiation in taking the depravity of their lives and making it a work of majesty.

I’ve seen Faith Healer on stage three times, and once streamed on television. Each time I’ve discovered more to wonder at. Is it Brian Friel’s masterpiece? Well, Dancing at Lughnasa is a strong contender, but possibly this one wins, as an act of faith.

Our rating: ★★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

29/03/24 Mike writes –

Power of Sail

By Paul Grellong, at the Menier Chocolate Factory.

Photos: Manuel Harlan

Our rating: ★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★

Interesting play, interesting cast, but for some reason this one just refused to engross most critics, nor two friends who saw a preview and were both disappointed. We were not.

Its title ‘Power of Sail’ references the rule that sailing ships have right of way over powered ships, but let’s not dwell on this seemingly irrelevant metaphor. Here we are in the rough seas of a university under pressure where the right to Free Speech is being tested to breaking point. Straight from today’s headlines, we are plunged into the controversy of whether a Right wing white supremacist should be allowed by invitation to disturb the safe space beloved of today’s unchallenged students. (I liked them referred to as “triggered children”.) Or should freedom of speech prevail over any misgivings.

This Cancel Culture topic is very 2024, perhaps a touch deja vu, but here it is given a fresh relevance with an assortment of characters representing differing views – the free speech professor (Julian Ovenden), the stressed university dean (Tanya Franks), the controlling black academic (Giles Terera), and the two conniving students (Katie Bernstein and Michael Benz). The play is described as A Moral Thriller – it sets itself up with a variety of contrasting views, plus Jewish concerns adding an extra edge of disquiet. The format of crime/ investigation/ interrogation has a police woman (Georgia Landers) probing the murky waters for what lies beneath. And it’s theme goes deeper – in six scenes each character is revealed to have a personal agenda, each character needs opposition in order to promote their cause or career, and a tragedy brings about this clash of wills. It further suggests we all ‘put on a face’ (here it’s ‘a code’), according to whom we are speaking, to suit our own agenda.

There’s a running thread about a barman (Paul Rider) who loves telling jokes which everyone resists. I thought it brave to eventually let this pirate joke be told, with us all nervous in anticipation. But it works, is appropriate to the theme, and has the right element of unexpected surprise.

With a neat back-and-forth time-line, we needed to pay attention to keep on track but are rewarded with an engrossing string of revelations and much to ponder after its open-to-discussion ending. We liked it a lot as did the audience – very well played by its cast and elegantly produced on the small stage with some adept scene changes.

Recently we have seen Nachtland, Hir and Merchant 1936, all of which seek to disturb our sensibilities and perhaps see their subjects from a different perspective. I like that. This fourth play does the same, makes us look at current concerns afresh and maybe rethink our perceptions.

I wonder if those who were less enthusiastic than us found the ‘thriller’ presentation at odds with what is a political concept in an unusual guise. The play’s abrupt end leaves us in deep water to decide a resolution for ourselves. But the play gripped us, developed well, and satisfied our expectations.

25/03/24 – Fredo writes –

Bluebeard’s Castle

An opera by Bela Bartók, at the London Coliseum

It’s an opera about a serial killer, and no, it isn’t Sweeney Todd. Bela Bartok’s only opera is rarely performed: it’s short and intense, and while it doesn’t occupy a whole evening, it’s difficult to pair it with another work. We were pleased to catch one of only two performances presented by the English National Opera this season.

It proved to be a high-risk production for the ENO. The cast features only two singers, Bluebeard and his new wife Judit. However, the singer who had rehearsed Judith was ill, and a new singer, Jennifer Johnston was parachuted in at short notice. She had arrived at 3.00pm, had two hours’ rehearsal and was on stage to sing the role at 7:30. That’s show business opera-style for you!

While Ms Johnston, in costume, sang her part at a lectern, Judith’s actions were performed by a young man, Crispin Lord, who is an assistant director with the company. Dressed in a singlet and Judit’s long skirt, his androgynous presence adds a surprise frisson to what must have been an already tense evening for John Relyea, singing Bluebeard. He also had a shadow; Leo Bill, who spoke the prologue, and stayed on stage throughout as all-purpose prop man.

It’s a strange work. Bluebeard brings his new wife to his castle and she probes the secrets behind each of seven locked doors, gradually revealing torture instruments, treasure hoards, and much more. As the music swells, the tension mounts, until finally Judit joins her husband’s earlier wives in an almost masochistic surrender. It’s an unsettling mixture of perversion and collusion, but Bartok’s rich and exciting score, conducted by Lidiya Yankovskaya, rescues it from being unsettling gloom.

Although it was advertised as a semi-staged version, director Joe Hill-Gibbin provided plenty of detail, a long multipurpose white table with blood aplenty, flowers and golden glitter, the lighting adding drama and tension. A coup de theatre provided the revelation of the previous wives.

Unusually for the ENO, it was sung not in English, but in the original Hungarian. A nearly-full house roared their approval as a blood-spattered Judith and Bluebeard took their bows. We joined in.

20/03/24 Mike writes –

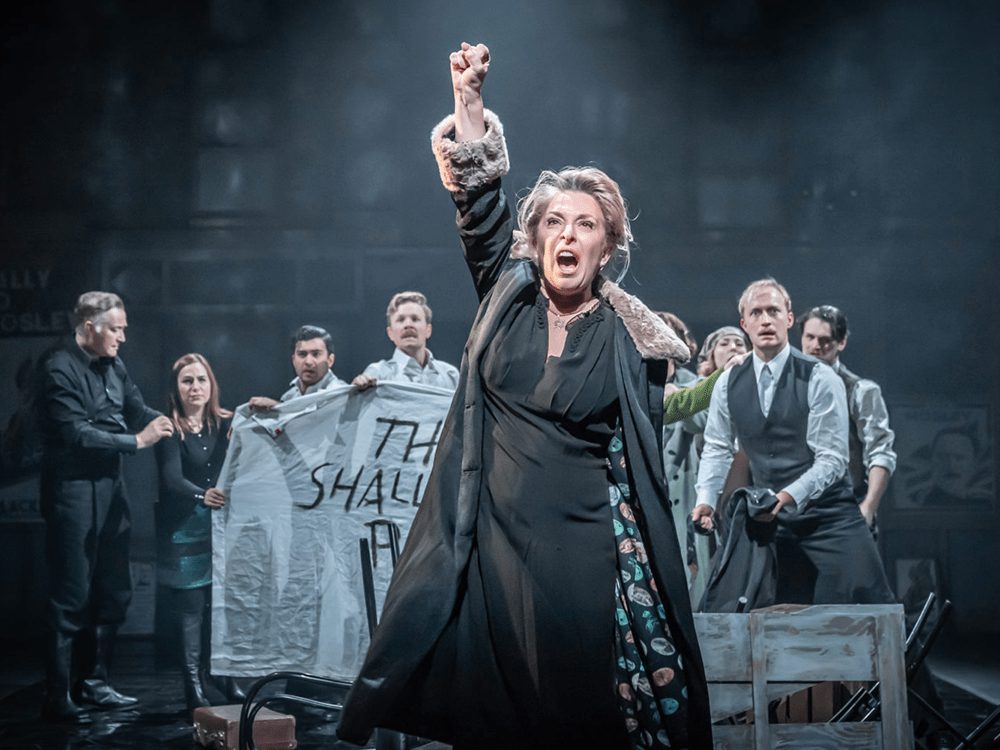

The Merchant of Venice 1936

By William Shakespeare, at the Criterion Theatre

I had always thought that Shakespeare was not nice to Shylock. All the other characters in The Merchant of Venice treat him badly, use him, make antisemitic remarks about him, and even his daughter Jessica cannot wait to get away from his clutches. Fredo assures me that audiences these days are more sympathetic to his plight than those on stage. Nevertheless, he usually disappears after his comeuppance, with no pound of flesh, leaving everyone else to their happy endings.

Not so here. Tracy Ann Oberman wanted to play Shylock as a Jew we could understand, in a more familiar situation. She resets the play’s narrative in her grandmother’s day, at the time approaching the 1936 Battle of Cable Street. Shylock becomes a Jewish widow trying to make a living against the rising popularity of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, with Shakespeare’s upper-class characters keen to slander Jews and side with the right-wing mob. Back in the day it was various socialist groups, trade unionists, anarchists and British Jews who challenged Mosley.

The revised play is a major gear change to the usual narrative but it certainly works. Projected newsreel snips and newspaper headlines set the scene effectively with the usual plot – a loan not repaid, gentlemen seeking marriage, and the unbridgeable class divide – all fitting seamlessly into the 1930’s social scene. And with the current Israel/Gaza war and the re-emergence of antisemitism always in our minds, the play wears its new relevance with pride.

The cast enter through the Stalls and introduce themselves to us with Jewish greetings, then segue straight into the play – the requested loan, suitors courting the ladies, bravado mixed with social tensions. At times there’s an uneven tone due to some amateurish performances, and the overlong casket scenes are too caricatured. You can get away with a flamboyant flourish better when dressed in Tudor garb than thirties suits and frocks.

But some performances are outstanding. Tracy Ann Oberman rules the stage convincingly as this matronly Shylock, forceful yet charismatic (and perhaps showing up the inexperience of some other members of the cast). Hannah Morrish as Portia excels both as posh love interest and then gender-switched as brisk male clerk. Jessica is oddly presented first in school uniform (‘underage’?) and later in sparkly thirties evening wear, but Gráinne Dromgoole just about pulls this off in time for the ultimate pairings….and the riot. The men-in-suits are arrogant city sharks, I expect intentionally so, given the feminist slant of the production. But it does all make sense.

The matinee house was packed and many were school groups. A lad sitting next to us was obviously bored and restless….until the end when we were all roused to stand in solidarity with all those on stage protesting against fascism. It animated him. A worthy success. Back on the street, I wondered which protest movement that theatre audience would be joining today.

Photos: Marc Brenner

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

16/03/24 Mike writes –

Hir

By Taylor Mac, at the Park Theatre

Photos by Pamela Raith

Click to enlarge

Our Rating: ★★★

Group appeal: ★★

Before you ask, Hir is pronounced Here. It’s a cross gender pronoun to add to all the They/Thems surfacing these days, in unexpected situations. It also refers to Here, because the society it examines is in transition as well. Young person, Max, is transitioning and wants to change from woman to a sissy male but is keeping all options open. But the first character we see is Arnold their comatose dad, face painted as a clown and dressed in pink wig and dress. He’s had a stroke and is now bossed and bullied by his wife Paige, revenging his previous abuse. She has fully embraced her changed family situation taking it to the (il)logical extreme, living in total domestic chaos, and exchanging all previous societal norms for a new eccentric freedom.

Then into this dysfunctioning household, son Isaac returns from Afghanistan where he was burying body parts. All he wants is the domesticity he was used to, before the transformation and transgendering of his family took a hold. It’s a different world for him and a new norm in home life. He sets about putting right what he sees as wrong, but this is an unwelcome outrage for Paige and Max.

Gender and sexual arguments and theories abound, ranging from the sex life of the octopus to the Mona Lisa being a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. From its opening OTT zaniness, the play settles into a cross between a farce and a dire warning, often too absurd but sometimes touchingly thought provoking.

We picked seeing this one not for the play but for its star player, Felicity Huffman, the leading Desperate Housewife from tv a few years ago. She puts her all into this full-on controlling mum, crazy but convincing too. But then Steffan Cennyddd takes over control in the major role of the returning soldier son, voicing the audience’s most reasonable responses to the increasing mayhem. Thalia Dudek (they/them) brings an androgynous appeal to Max, and we cannot but feel sympathy for Simon Startin, continually humiliated as both dad and actor.

Considering the Park’s purse, congrats must go to the design and production team for a detailed living-room set, in spectacular disarray, which has to be tidied and cleaned before Act Two, then of course reset in disarray for the next performance. It’s an obstacle that cast and stagehands overcome with apparent ease.

Finsbury Park is transforming, so Huffman at the Park is perhaps the bargain version of say Parker at the Savoy.

13/03/24 Kathie writes –

Nachtland

By Marius von Mayenburg, at The Young Vic

Directed by Patrick Marber, this 95-minute play, set in present-day Germany, is a roller-coaster of challenging themes, views and actions. Performed on a thrust stage, initially covered in the detritus to be found in many attics, this one belongs to the recently deceased father of Philipp and Nicola. The siblings with their spouses emerge to carry away the profusion of items, silently, in the opening 10 minutes or so. Left with a nearly empty stage, the discovery of a small wrapped package leads to the revelation of a framed watercolour.

The dialogue, between each other plus some directed at the audience, makes it clear that there is considerable tension between the siblings, which carries over into their reaction to the painting. The sister dismisses it as a daub to be thrown away but Philipp quite likes it. Out of its frame, a signature is spotted, one A Hitler. Discussions follow, about the money it could realise mostly, and very little about the moral situation which is the focus of Philipp’s wife, who is Jewish. An art expert is called in who confirms that it is by the young Adolf, but further evidence as to provenance is needed. Rescued from the rubbish is a case containing things belonging to Grandma Greta, an opera singer who was a paid-up member of the Nazi party and mistress of Martin Bormann. A buyer is found.

We are artfully lead along opposing, yet disturbingly plausible views – “well, everyone belonged to the Party – it didn’t mean anything” – and draws out that none of these particular characters have any sympathy or understanding that Philipp’s Jewish wife could be horrified by the thought of profiting from the sale, or even the painting’s continuing existence. The antisemitic veil is very thin and the subject of Israel and Palestine is also given a focus. (This play was written in 2022) The story even manages to introduce sexual issues, including a scene involving the buyer in fetishist underwear dancing in the presence of the art expert. The list of content warnings by the Young Vic is extra long!*

The play was very well served by the cast with John Heffernan as Philipp and Dorothea Myer-Bennett (replacing Romola Garai who withdrew a month before opening) as Nicola. Gunnar Cauthery and Jenna Augen played their spouses. Jane Horrocks was splendidly chilling as the art expert and Angus Wright (happily, mostly not in his cut-away leather pants) was the buyer. The gasps from the audience at times clearly indicated how deeply we had been drawn into the story. An intense but rewarding 95 minutes.

Our rating ★★★★½ / Group appeal ★★★

Photos: Ellie Kurttz

*Mike adds – Here is a Link to all the trigger warnings for this production. It not only gives a list of everything which may “trigger” an unwelcome response in certain members of the audience, it also gives the timings, minutes and seconds into the running time, when such triggers occur. I give this link as an example of the ludicrous lengths some theatres are going to “to protect” those supposedly vulnerable members of the audience who in my opinion should stay away from every theatre in the land, snowflakes scared of the big bad world beyond their “safe space”. Theatre should excite, challenge and sometimes offend, as well as entertain us. We should not be protected from its demands upon us.

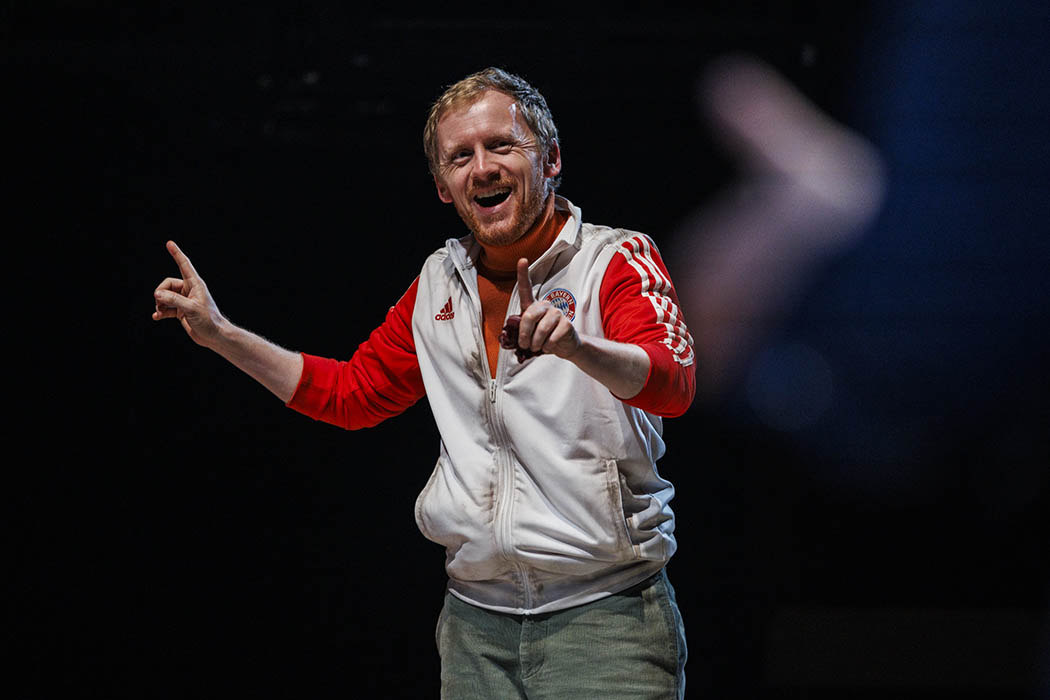

11/03/24 Mike writes –

Jenůfa

An opera by Leoš Janáček, at the London Coliseum

We always enjoy our visits to the ENO dress rehearsals, thanks to our friend Meryl; it’s a chance to see a new production before the reviews may influence our expectations. Hit or miss, these occasions are always of interest. Not only are they ‘live theatre’ but also a final try-out before the production is set for its Press Night. Maybe not everything is perfect yet, and the singers are not obliged to ‘sing out’, but everyone just hopes all good intentions will pay off. On this occasion that did not quite happen.

It was partly our fault – we had another obligation after the 2.30pm performance so needed it to run on time. It did not, and we had to leave before the end. It was partly the production’s fault too – they had trouble needlessly building part of the set out-front beyond the curtain and the interval was extended while stagehands did their best to fix a rogue ‘flat’. And then, in mid scene, a window blind fell on Jenůfa while she was in mid aria – fortunately it was only cardboard and she battled on without missing a note. But we had to leave early and missed the dénouement which I suspected would not be a happy ending, given the cumulative tragedy of the developing plot.

I shall quote the ENO blurb – “A tale of honour, love and sacrifice, Jenůfa explores the stigma of pregnancy out of wedlock against the backdrop of a small community.” It’s another distressing tale of family dysfunction, jealousy, brutality, and a baby drowned in icy waters. I apologise for the spoiler but it’s easy to guess that this clash of temperament and morality is not going to work itself out. But no, I’m wrong – according to the synopsis which I had to check afterwards – there is a resolution to the tragic developments. It was unfortunate we had to bail out in mid misery.

Visually, it was sparsely set with long shadows or flooding lights to enhance the drama. Characters were often placed irritatingly at the sides of wide-open angled spaces, “a 20th century industrial estate in the Eastern Bloc” given an impressionist representation.

However, we certainly did enjoy the opera and thought the orchestra and singers were on splendid form, doing justice to the exciting and emotive score. A large chorus was well choreographed in their group movements and outbursts of drunken revelry, and created an impressive sound. We particularly liked Jennifer Davis as Jenůfa and Susan Bullock as her wicked stepmother. But I objected to the “handsome but irresponsible” Steva the male lead, and Laca his half-brother, both being oafishly miscast as ugly bulls of men. As Jenůfa’s competing love suiters, neither could be handsome or appealing in her eyes. However, that’s opera for you, and regrettably voice is given preference over what we see – a balance would be better.

This is a revival of ENO’s earlier production which received much quotable praise so I hope it finds the audience it deserves.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

Photographs: Tristram Kenton (Click to enlarge)

02/03/24 Fredo writes –

Djevjka sa Zapada/La Fanciulla del West/

The Girl of the Golden West

by Giacomo Puccini, at HNK Zajca, Rijeka, Croatia

We’ve been away on our own, to Venice, Trieste and Rijeka. On our return to Venice from Trieste, we fell into conversation with a young man from Padua on the vaporetto. We told him we’d been to Rijeka in Croatia to see an opera. “Rijeka? Oh, in Italy, we call it Fiume,” replied il Padovino, smiling. ”It used to belong to Italy, but we lost the war.”

In fact, both Trieste and Fiume were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the former was the main port for Austria, and Fiume served Hungary. But that was a long time ago; World War 2 – not such a distant memory!

We’d joined a coach trip (yes!) of the Friends of the Trieste Opera, organised by my Italian cousin Elisabetta (it’s an unfortunate family trait). And no, it wasn’t a triple bill: it was Puccini’s The Girl of the Golden West – I’ve given the Croatian and Italian titles just to show off.

This is perhaps Puccine’s least frequently performed work, and there was some excitement on the coach as it hasn’t been seen at either the Teatro Verdi in Trieste or at La Fenice in Venice for about 50 years. It’s based on a play by the American David Belasco, who also provided the source for Madama Butterfly. Why is it such a rarity? Our guess is that there is only one substantial female role, with another very minor female character, and the chorus is totally male.

Puccini also eschewed the show-stopping arias which made him famous. The music is lovely, and the singers are given plenty of opportunities in recitatives and duets, but there is no equivalent of Vissi d’arte or Un bel di. When the tenor finally lets rip in Act Three, he was rewarded with applause, perhaps from a sense of relief from the audience that Puccini hadn’t lost his touch.

The opera is set in Minnie’s saloon in a prospecting town in California. We were treated to an introductory film for overture, with traditional Western-style graphics to set the scene. The plot was fairly easy to follow – just as well, as it was sung in Italian with Croatian surtitles. Fortunately, Elisabetta and her colleague Rosanna had provided us with a plot summary before the show.

Gabielle Mouhlen and Ivan Momirov had suittably Puccini voices for their leading roles as Minnie and Dick, while Giorgio Surian provided menace as the Sheriff, as well as directing the opera.

We enjoyed it immensely. It was interesting to see the well-preserved opera house, with two ceiling panels painted by the young Gustav Klimt, and to spend the day travelling through a narrow stretch of Slovenia in the rain.

Mike and I were interested to see how Elisabetta and Rosaana organised their outing. It won’t surprise you to learn that I couldn’t resist giving her a few tips.

Our rating: ★★★★

Foto: Mateo Levak

01/03/24 Fredo writes –

L’Oro del Diavolo – The Devil’s Gold

Music by Marco Podda, Libretto by Elisabetta D’Erme, at the Sala Victor De Sabata – Ridotto del Teatro Verdi, Trieste

Yes, Mike and I had travelled to Trieste especially to see this new 75-minute opera for children, performed in the spacious and rather splendid studio of the Opera House. No, it wasn’t our dedication to the works of the Brothers Grimm, nor the music of Marco Podda. We have to declare an interest: Elisabetta D’Erme, who wrote the libretto and acted as Assistant Director, is my cousin.

This was her first experience as a dramatist, and a reluctant one at that. The opera was commissioned by the Artistic Director of the Opera House, and the composer approached Elisabetta to write the words. She declined the invitation, as she had other irons in the fire, but eventually agreed to meet him to discuss the project.

That was two years ago, and here we are, settling down in front of Francesco Castellana and his 43 piece orchestra. We were slightly disconcerted by the black-clad figures making their way through the audience, but these were students from the Conservatoire acting as chorus.

In fact, the entire cast spent much of the performance moving through the audience in Oscar Cecchi’s fluent production. We were sitting behind the central gangway, and could participate fully in this immersive experience. If you haven’t had an operatic bass standing beside you going full throttle, you haven’t lived.

It was sung in Italian, and it’s difficult for us to judge Elisabetta’s contribution. She had given us a fairly lengthy summary of the plot – a greedy, despotic King, a simple boy who gets set upon by brigands and goes to Hell to steal the Devil’s gold, and love and other complications, and punishment for the King – oh, and a happy ending, of course. We were able to discern that Elisabetta had provided narrative propulsion, and that the complicated tale unfolded clearly and swiftly.

Signore Podda’s score was rich and lush, and the powerful orchestra produced a sumptuous sound. All the singers sang wonderfully, with several outstanding arias.

There was, unfortunately, one major handicap. The leading role of the hero was originally written for a tenor, but Signore Podda took the bizarre decision to transpose the music for a mezzo-soprano: his wife. Giulia Diomede sang beautifully, but there was no way of convincing us that this womanly figure was an adolescent boy. This emphasised her limitations as an actress, and the characterisation of a backward, immature youth imposed on her was another impediment. To make matters worse, she was forced to wear a wig that looked as though she was carrying a red chicken on her head.

It was an ambitious enterprise, and we marvelled at the Teatro Verdi making the resources available. Most of the performances were for schools, and we’re told that the children are very enthusiastic and energised by it.

Although Elisabetta and her friends had reservations about a coda written solely by Marco Podda – they felt that it introduced a questionable moral for a children’s audience – Mike and I enjoyed it hugely, and hope that it will have an afterlife in other adventurous opera houses.

Our rating: This was the motive for our visit to the elegant city of Trieste, and our reunion with my cousin making her dramatic debut. A star rating would probably be inflated and unreliable.

17/02/23 Fredo writes –

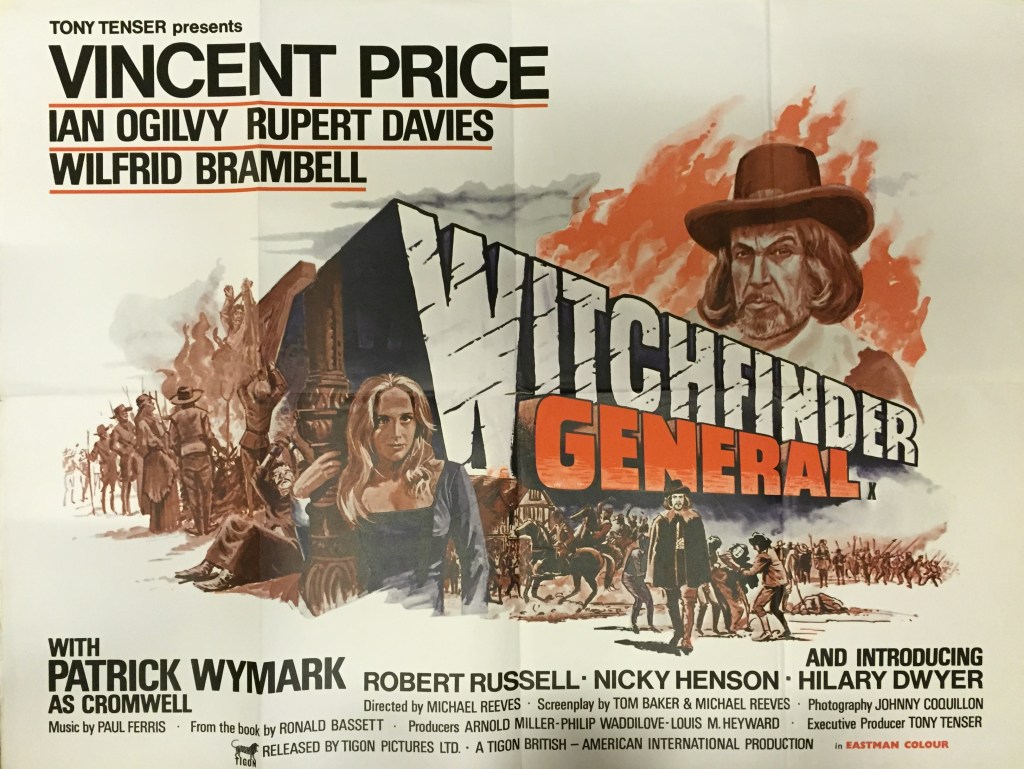

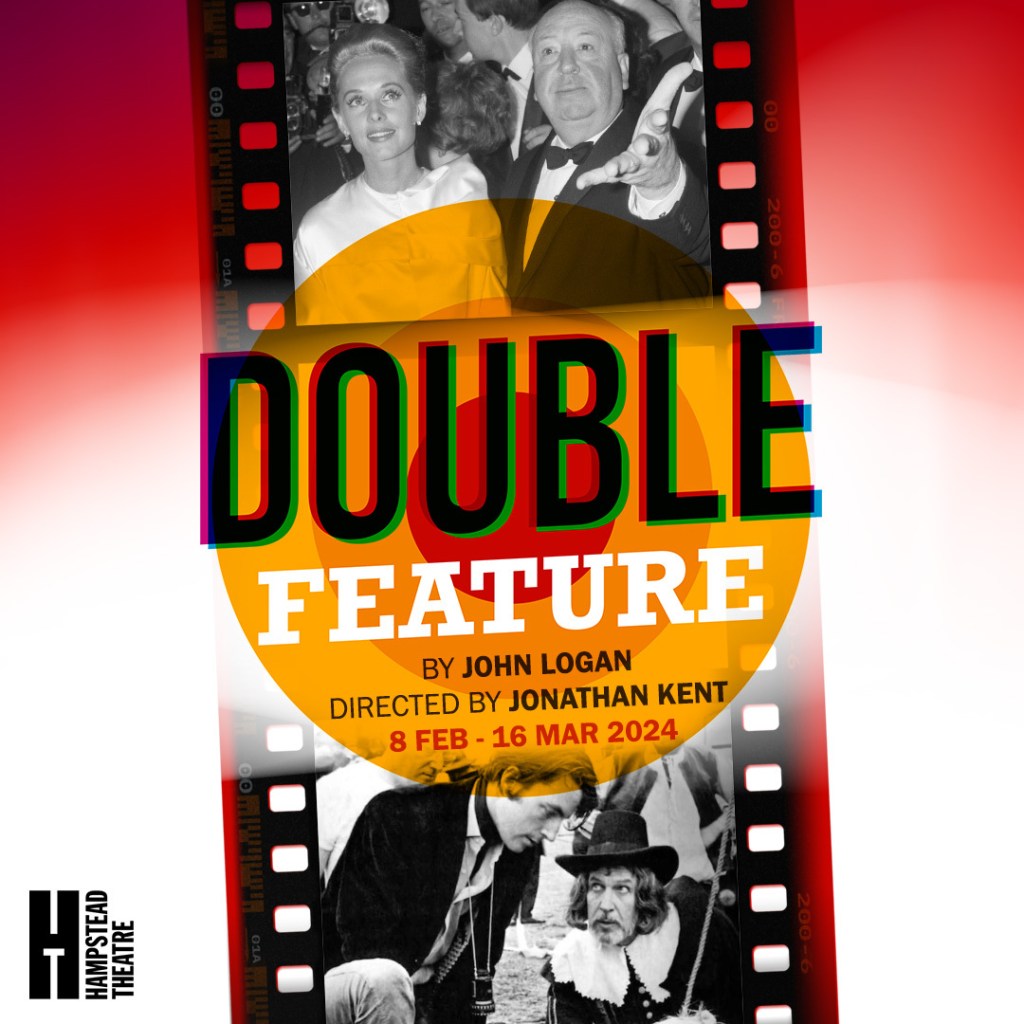

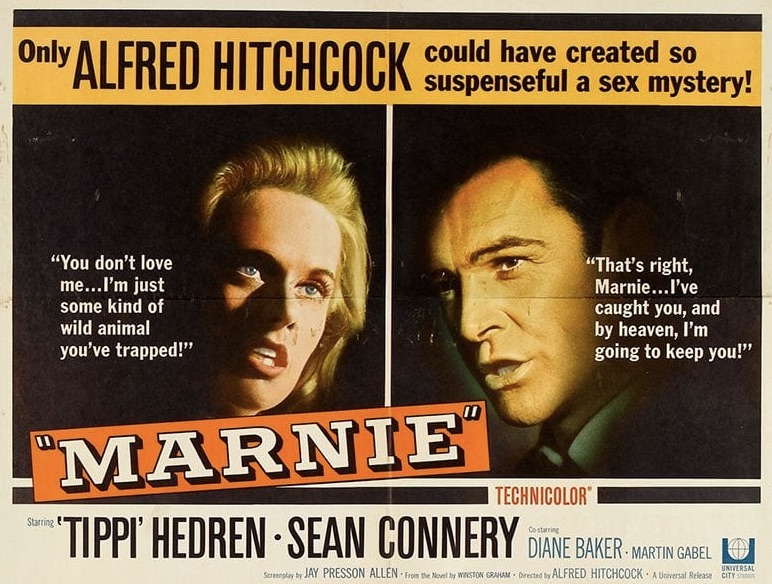

Double Feature

by John Logan, at the Hampstead Theatre

It helps if you know the movies. Double Feature focuses on two separate confrontations between two directors and their leading players, while filming Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General and AlfredHitchcock’s Marnie. Fortunately, Mike and I are well versed in the work of Alfred Hitchcock. However, we both flunked out of horror movies, even the cult series based on the stories of Edgar Allan Poe directed by Roger Corman and starring Vincent Price. I don’t think that mattered a great deal, as John Logan’s script fills in the behind-the-scenes details on the set of both films.

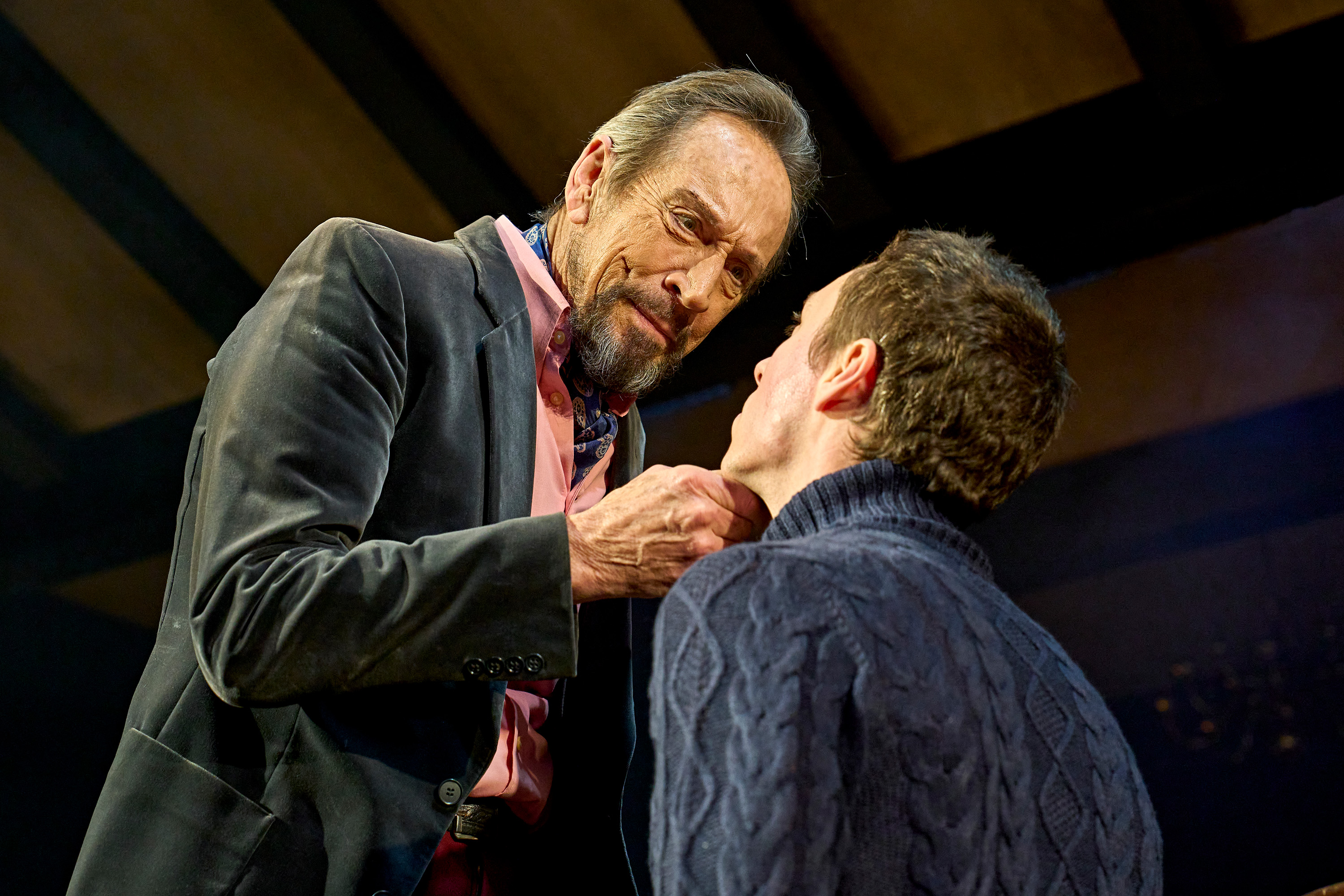

This was going to be the breakthrough movie from Michael Reeves, directing his third feature. Tensions have erupted on the set, and the star, Vincent Price, is going to walk. In his Suffolk cottage, they square up to each other, pitting their experience against their talents.

In another Suffolk cottage, this one recreated in Los Angeles on the backlot at Universal Studios for their leading director, Alfred Hitchcock, another performer, Tippi Hedren, pleads her case. She has been summoned by her mentor, who appears to have planned much more than just coaching her in the next’s day’s scene, for their new movie, Marnie.

The two stories are interleaved, and played out on the same cottage set, with all four actors on stage for most of the time, occasionally picking up cues from each others’ stories and repeating key phrases. So far, so Alan Ayckbourn; but what does it mean? I enjoyed the peep behind the screen, yet for the first hour I worried about what writer Logan was getting at.

I needn’t have fretted. As Reeves and Hitchcock struggle to gain the upper hand (in Reeves’s case, with a greater degree of desperation), the actors reach a compromise with their director. Jonathan Hyde has a masterly scene where he changes his interpretation of a speech under Reeves’s direction. Meanwhile, Tippi Hedren is forced to consider a blunt proposition from Hitchcock, staged with the sort of coup de theatre so beloved of the Hampstead stage-management. Logan’s theme becomes clear: it’s about creativity and the pressures placed upon artists by money, power, ambition and insecurity, and what we are prepared to relinquish to get what we want.

It’s a handsome production from Jonathan Kent, who gets assured performances from Jonathan Hyde as Vincent Price and Ian McNeice as Hitchcock. I wasn’t sure about Rowan Polonski asReeves in his early scenes, but he gained conviction as the play developed. The revelation was Joanna Vanderham as Tippi Hedren. As a younger actress, she had seemed rather vapid in her stage appearances, but she brought gravitas, confidence and vulnerability to this portrayal. There was a long line of Hitchcock Blondes – Madeleine Carroll, Joan Fontaine, Grace Kelly, Doris Day, Kim Novak, Janet Leigh – and Ms Vanderham shows that she could stand with the best of them.

It made us want to search out these two old movies and watch now with renewed interest.

Photos: Manuel Harlan

Our Rating:★★★ / Group Appeal:★★★

Footnote: Michael Reeves continued to have problems with the studio over Witchfinder General, and became depressed. He died, aged 25, from an accidental overdose of barbituates before the movie was released. Tippi Hedren was no great shakes as an actress, yet she did star in two films for Hitchcock, and had a small role in A Countess from Hong Kong, the last film directed by Charlie Chaplin. She made a lot of movies and television appearances to fund the compound for lions and tigers that she maintains at her home. As of 2020, she had more than a dozen! She is the mother of actress Melanie Griffith and grandmother of Dakota Johnson.

06/02/24 Mike writes –

The Little Big Things

By Joe White, adapted from the book by Henry Fraser, songs by Nick Butcher (music and lyrics) and Tom Ling (lyrics), @sohoplace theatre.

Photos: Pamela Raith

Our rating:★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★★

Why would anyone want to make a musical about a guy in a wheelchair? These are the first words uttered in the show…from the guy in the wheelchair. He plays Henry Fraser whose true story this is. In fact there are two guys playing him, one as he was before his dive into a too-shallow sea, and the other as the active wheelchair user he is now. From a lively 17 year old who loved rugby, he eventually transformed himself into a writer and artist using computer skills and a paintbrush between his teeth. It’s his story, it’s his musical. And it soars.

It’s no sob story, there’s no mawkish sentiment here, just encouragement, persistence, some soul searching, and above all the joy in living. It races along with the verve of Six and other contemporary musicals. The show is mostly sung-through, with the music and song pushing the pace of the story-telling, and developing the tested family relationships between Henry, his parents and three brothers. It also gives powerful support to the physiotherapist (confined to a wheelchair too) as she builds Henry’s morale and teaches him new ways of living. It’s music as therapy, for him and for us.

It helps that all the characters are personable and believable in their variety of reactions to this tragedy. They are clear-cut types, no surprise deviation from our expectation, but we remain happy to hang on in there with them, to their touching, ultimate triumph over adversity.

The stage is continually awash with colour bringing a bright atmosphere of hope to a sparse square arena; a platform occasionally rises from the floor to showcase a character and picture frames descend from above. The players rush on and off from the four corners moving props, and those wheelchairs never stop twirling.

It was good to see Linzi Hateley as Mum, bravely concerned but, most important, warm and supportive. The three brothers (plus the younger Henry) were….brotherly, visually different but indistinguishable in character one from the other. Amy Trigg as the forceful therapist shone brightly, but Ed Larkin as the older disabled Henry carried the show on his four adroit wheels.

The packed theatre had a great time. We did too.

03/02/24 Fredo writes –

Till the Stars Come Down

By Beth Steel, at the National: Dorfman Theatre

Here’s the winning formula for writing a successful play: take three sisters; and set it at a wedding, where there’s lots to drink, and have things get out of hand in the second act. Early sparring and humour should give way to recriminations and arguments, and more home truths follow in act three.

Throw in a bit of tension about immigration, and some festering resentment about the Miners’ Strike, and I guarantee you a rave review in The Guardian.

Does this sound like I didn’t like Beth Steel’s play? No, you’re wrong; it’s hugely enjoyably and expertly acted. The comic lines fly around in the first act, as the women prepare themselves for the wedding, and you need sharp ears (and perhaps a hearing device) to catch all the punchlines from the slowly revolving stage. My shoulders were still shaking at one of Lorraine Ashbourne’s perfectly timed zingers several minutes after everyone else’s laughter had died down (and I’m not known for my sense of humour).

Ms Ashbourne does a lot of the heavy lifting in that act, but Lisa McGrillis then takes centre stage as the sister who wants something she can’t have (there’s one in every family). It’s a perceptive and sympathetic performance from the actress who will always be remembered as the ditzy girlfriend in Mum, and it’s good to see her flex her acting muscles in a completely contrasting role.

There’s a surprise thread introduced late-on to the plot which caused a gasp throughout the audience. We could anticipate future unravelling of the family dynamic. However, Steel introduces subjects that she doesn’t thoroughly explore: prejudice, the harm that lies can cause, unresolved conflict – fallout from the Miners’ Strike comes on as an after-thought. Perhaps author and audience were having too good a time at the start. It leaves Lucy Black and Sinead Matthews with less to do than expected, and with mounting levels of stridency, while the male roles are a bit under-nourished.

However, the pressure builds. The audience loved it, and I had a good time as well. But it’s like a slab of wedding cake: rich and fruity and nutty with a generous layer of marzipan and shards of royal icing, but it doesn’t make a satisfying meal. Forget The Guardian’s 5-star review. It’s a 4-star production of a 3-star play.

My rating:★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★★

Photos: Manuel Harlan

30/01/24 Mike writes –

Stranger Things – The First Shadow

by Kate Trefy, the Duffer Brothers and Jack Thorne

I did my homework and took myself off to Hawkins Middle School. I knew strange things were happening there. All around the world there was a buzz about the disappearances from classrooms, and wild tales were being told about unseen supernatural monsters and rumours of covert experimentation.