Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2022

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2021

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2020

30/12/23 Mike writes –

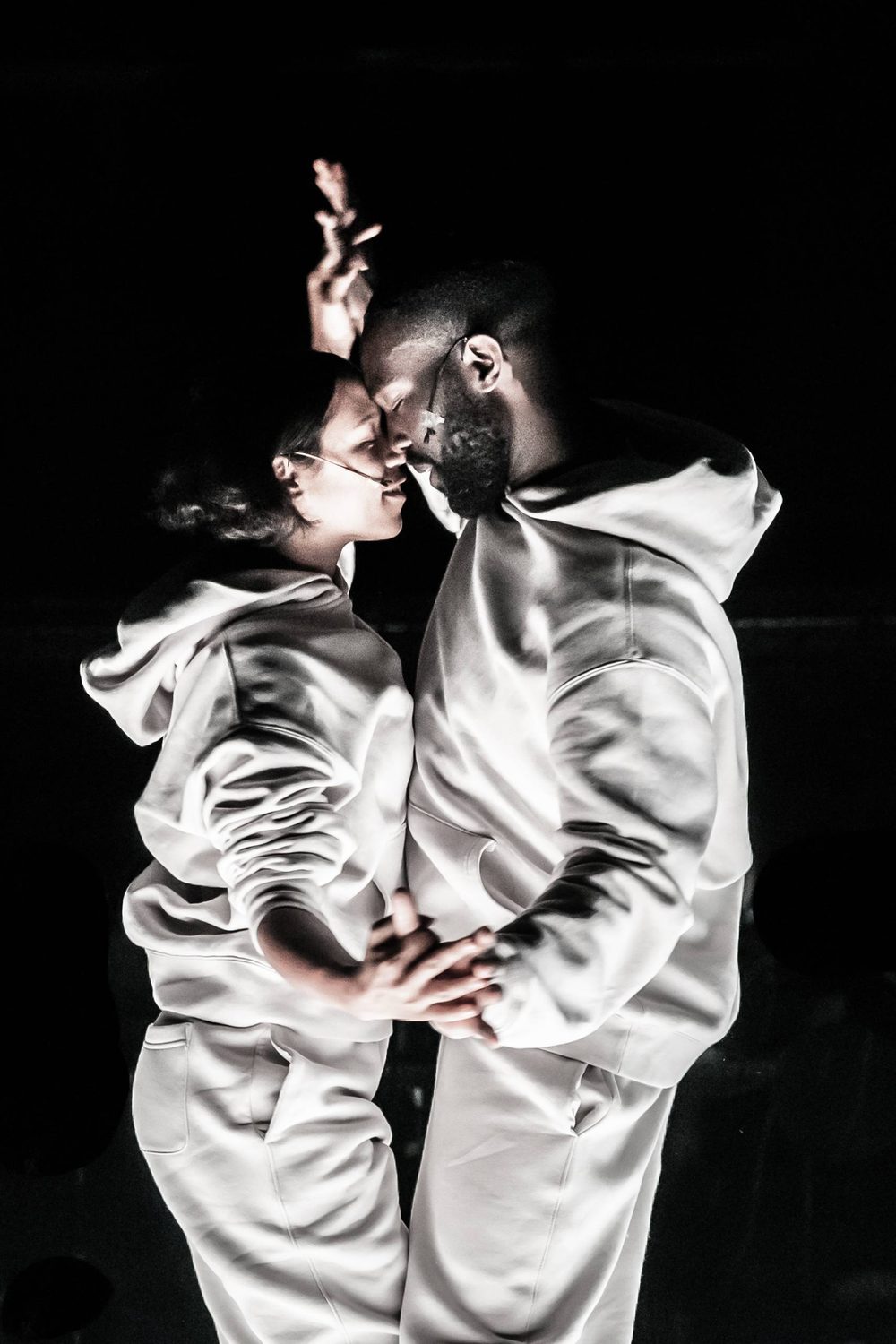

Cold War

Book by Conor McPherson, Music by Elvis Costello, Based on the film by Paweł Pawlikowski, at the Almeida Theatre

Photos: Marc Brenner

We admired the 2018 Polish film “Cold War” and this stage musical adaptation had high flying credentials – book by Conor McPherson, songs by Elvis Costello, and directed by Rupert Gould. We saw it just after Christmas so perhaps our spirits were too high for such a sad and retro love story. We remembered Conor McPherson’s heartbreaking ’Girl from the North Country’ which used Bob Dylan’s songs for a sad tale of folk scraping a living in reduced circumstances – this brought devastating results for the fictional characters as well as for the audience. More of the same, please.

This was not to be. It began uncertainly with auditions for a folk music show which reminded me of those song’n’dance Folk Evenings (with embroidered waistcoats, frilly aprons and ribbons) that we are always offered on European Tours. A couple, ill-matched in character, meet in 1950s Poland – he plays the piano, she sings plaintive songs – they bond, they part, they meet again in different circumstances then part again. It’s the time of the Cold War in Europe: can borders be crossed (both geographical and temperamental) to ensure a resolution to this tale of love in a Cold War climate?

When Wiktor meets Zula they sort of click, but argue too and to me their relationship suggested antagonism more than magnetism. Zula remains in the East when Wiktor flees to the West. In both zones traditional songs are being rewritten either for communist ideals or commercial profit – oppression is political in East Europe but commercial in West Europe.

Of course musicals have historically taught us that love changes everything, but the love here never radiates any genuine emotion beyond the stage. The songs are just perfunctory pauses in the plot, and the occasional folk dance routine is strictly a temporary change to the forlorn tone. The musical numbers are directed at an unseen audience and we hear recorded applause, a killer of real applause, so there is no live audience response to the ‘entertainment’ until the interval and final curtain.

My reaction was at odds with the Islington audience who applauded with enthusiasm at the end, perhaps to show off their politics more than their pleasure. Certainly the cast did their best with the material – Luke Thallon had the measure of his role as Wiktor but his subdued portrayal would have been better suited to film than stage; Anya Chalotra’s Zula was unable to overcome her charmless script. Alex Young is wasted in a minor role. The other cast of more than a dozen fulfilled numerous roles with enthusiasm.

I feel I should praise all the effort by cast and company put into the staging but hold back on praise for the writing which really did not do justice to the original film. My rating will be an average for overall effort, and certainly less than the many 4 star reviews given by newspaper critics.

Our rating:★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★

16/12/23 Fredo writes –

She Stoops to Conquer

by Oliver Goldsmith, at the Orange Tree Theatre

There are good reasons why Oliver Goldsmith’s comedy has remained popular since it was first seen in 1773. It has likeable characters, humorous situations and a happy ending – something for everyone, a comedy tonight! This latest incarnation on the Orange Tree’s tiny in-the-round acting space makes small gestures towards updating it to the 1930s, but there’s scarcely a hint of P G Wodehouse to the proceedings. Instead, the ‘mistakes of a night’ are played for all they’re worth by an expert cast.

Veteran David Horovitch is an old hand at this game, and we’re in safe hands there. Who would have predicted that Greta Scacchi, so often used as eye-candy in movies in the 70s and 80s, would develop into a comic character actress, gamely letting herself go to add to the fun? Or that rising star Tanya Reynolds, so intense in the downbeat A Mirror (at the Almeida) would revel in such a spirited performance?

For me, the acting honours go to Freddie Fox, expertly transforming from tongue-tied suitor to would-be seducer, and all the while demonstrating his own sheer enjoyment in performing. The play lights up when he’s on-stage, and in truth, it doesn’t flag even when he’s not there.

This play used to adorn the West End regularly with all-star casts. It’s reassuring to know that there are still actors with the skills to make it sing.

Our rating:★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

15/12/23 Mike writes –

The Homecoming

by Harold Pinter, at the Young Vic Theatre

(View from our front row seats)

The question was asked this week (by Clive Davis of the Times, following his ★★ review) – Is The Homecoming a masterpiece, or is it showing its age? It’s a play with longevity, often reappearing in different interpretations, often dependent on its cast or director, much like Hamlet or Hedda Gabler, or revivals of Miller and Stoppard. And of course Pinter.

The Homecoming dates from 1965, certainly of its time but is it for all time, is it relevant out of its original context? I think the answer to Davis’s question is Both – its original qualities do not fade with age, you just view them from a different perspective. No play, once a classic of its time, should fall victim to the vagaries of subsequent political thinking.

You may remember this is the one where academic Teddy brings his demure wife Ruth back from America to meet his all male North London family household – father, uncle and two brothers – all aggressive, chauvinist, old-school monsters. By the end (Spoiler, but well known by now) Ruth becomes a whore for the household, but on her own very strict terms to ensnare the men. To some it’s a misogynist male fantasy, but to others it shows feminist power. Like or detest it for its characters and plot, it remains one to shock and linger in the memory, regularly bouncing back from history with various directors’ new ideas. For me it’s a play of importance and arguably a masterpiece because of the way it forever resonates with its audiences in so many different ways, faces up to our fears or fantasies, confronts our expectations, and reaches parts of our consciousness we may not want disturbed.

This time, director Matthew Dunster avoids any realistic style – the fifty shades of grey stage is filled with mist as thunderous percussive sounds greet us when we enter. The natty suits and the the Dansette playing Connie Frances are the only reference points to the otherwise timeless presentation. This seemed right, but I thought less appropriate was Ruth presented as a demure dolly-bird instead of a femme fatale. And the weak Teddy had nowhere to recoil from as he became the surplus reject.

Today’s audience found more to laugh at in the play than I remember, but was it humour or those other triggers of laughter – nervousness, embarrassment or surprise? I missed the signature Pinter tension and apprehension here, though sudden outbreaks of violence, isolated in a spotlight, were highly effective.

Jared Harris leads the cast as Max, the father (much bombast but to little affect), but most impressive is Joe Cole as the self-important son Lenny, pimping, prancing and pernickety, but a fuse waiting to be lit; a riveting performance. I felt that Lisa Diveny, as the wife Ruth, lacked the undercurrent of sexual tension necessary before a too sudden change into eager provider of requested sexual services. Nevertheless, two of the men collapse symbolically at her feet here, neutered. Fredo informs me the final tableau vivant is a Pietà pose, certainly an appropriate and thoughtful image on which to fade the lights.

It’s still a play to relish, but this presentation added little more than a modern flourish to the text. Interpretations may falter, but the play’s classic stature remains.

My rating:★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★

Photos: Manuel Harlan

14/12/23 Fredo writes –

Infinite Life

by Annie Baker, at he National: Dorfman Theatre

Photos: Ahron R Foster

Our rating: ★★★½

Group appeal: ★★

It’s wrong to say that Annie Baker’s plays are an acquired taste. You either like or loathe them straight away. And if you take to them, you’ll be absorbed by the small details that we notice because the plays happen in real time. When someone leaves the stage to fetch a drink, we wait for the off-stage kettle to boil. You’ll feel the response forming in the mind of one character as they absorb (slowly) the information they’ve just received. A tilt of the head can convey a seismic change of direction. In dramatic terms, this can seem excruciatingly slow, yet has a fascination and humour. But if you don’t like this deliberate approach, her plays can be like watching paint dry.

This is the fourth of her plays to be imported by the National Theatre. Previously, The Flick and John were enthusiastically received; The Antipodes, less so. This time, director James Macdonnald has brought over the entire New York cast, and it’s like hearing a chamber orchestra give a virtuoso performance.

Sofie has come to a spa/clinic to relieve her chronic pain. She’s started a fast to rid her body of toxins, and as she lies on a lounger trying to concentrate on her book (Daniel Deronda by George Eliot), she gets into desultory conversation with four other patients. It’s Sofie’s first time, but they’re veterans, all at different stages of their fasting and all still wracked by unspecified and perhaps untreatable pain. They’re a Greek chorus on the tragedies of everyday life.

Is pain a metaphor for their lives? Nelson, the only man who appears, tells us that it is. In the play’s most controversial scene (walkouts were reported in New York) he and Sofie tell each other of their sickness and its manifestations. It’s a frank and brutal exchange, played to perfection by Christina Kirk and Pete Simpson. His condition is probably terminal, and hers incurable. Yet he seems to be a life force: his first appearance, walking shirtless before the women and creating an undeniable sexual frisson, is one of the play’s funniest moments. Later, he offers to have some form of comforting sex with Sofie, understanding that her complaint has rendered her incapable of a full sexual experience without unbearable pain. She declines: it would be a temporary consolation, and would resolve nothing for either of them.

Pain continues, life goes on. The final words go to one of the older women, played by the elfin Marylouise Burke. We’re in it together; we accept and endure.

15/11/23 Fredo writes –

The Time Traveller’s Wife

Book by Lauren Gunderson, Music and Lyrics by Joss Stone and Dave Stewart, at the Lyric Theatre

Photos by Johan Persson

I don’t like writing bad reviews, but there are times I have no choice. This is one of them. The show is dire.

Let me try to find a few redeeming features. Joanna Woodward sings strongly and has an appealing stage presence. David Hunter is less successful as the Time Traveller, and has to go through embarrassing contortions when he’s about to disappear into another time zone (then reappear naked until he grabs some clothing).

They’ve spent money on the special effects and the set, which is very high-tech with monolithic blocks and projections (though at various times the actors have to manhandle the furniture on to the revolve before it spins out of sight).

However, the story is confusing, and the plotting inconsistent, and I’d be flattering the writer if I describe the dialogue as banal.

(Mike interrupts – Both wife and husband age naturally but the Time Traveller can visit his wife’s ‘now’ from his past or future age. Confusing? I wish I’d gottit while watching the show but I guess most of the audience were fans of the book so didn’t need clarity. You can watch this adult man chatting up a young girl before she became his wife (!) or comforting her as an older man while she is a young woman. It’s supposed to be romantic but is just blandly sentimental. And would be a bit yucky if it wasn’t for Woodward’s appealing performance.)

The most egregious fault lies in the music and lyrics. Joss Stone and Dave Stewart (from The Eurythmics, for Heaven’s sake) both know something about writing songs, but their talent appears to have time-travelled to another dimension. There isn’t a memorable tune or an intelligent lyric in the entire score. I could go on, but I’m going to stop before I start enjoying myself.

Mike and I were guests of NIMAX Theatres, and perhaps we were at a disadvantage because we aren’t familiar with the best-selling novel by Audrey Niffenegger or the subsequent movie and television series. And the new genre of sci/fi-romcom has passed us by. The rest of the audience seemed to enjoy it.

Our rating: ★

Group appeal: It had form as a popular novel and movie, so possibly ★★★ though I had no enquiries about it.

13/11/23 Mike writes –

Roald Dahl’s The Witches

Book and Lyrics by Lucy Kirkwood, Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy, at the National: Olivier Theatre (a Preview performance)

Rehearsal photos

Forget pointy hats and pointy noses, along with those Wicked green faces and all that ’toil and trouble’. The witches here are all down-home types, dressed by M&S and are probably members of the WI. But they like to squish children and have diabolical plans to turn kids into mice and then rid the world of them. Roald Dahl knew that kids like horrible stories and now his book has been given the full National Theatre spectacular musical treatment, no expense spared. And it’s wonderful, provided you are over 8 years old. And even over 80.

Katherine Kingsley rules the coven as the Grand High Witch, evil dressed to kill in the fashion sense, with voice at full throttle. She points a long finger at possible victims, including ones in the audience and at one point chastises the owner of a ringing mobile ordering them out of the theatre (but of course that might be a set-up).

Little Luke leads the kids in their fight-back, a huge heroic performance for one so young (maybe 10) and then there’s Bruno, a posh’un from private school who leads a song’n’dance number like an old Vaudeville pro, amazing. Helga helps out as head-girl of a large young ensemble. I wish I could mention all their names but of course three children are cast in each role for different performances.

The Grown-ups are lead by Daniel Rigby as Mr Stringer, put-upon proprietor of the hotel where the NSPCC are meeting to plan not the protection but the extermination of the children. But first the witches have to fix gruff Gran from Norway, played by Sally Ann Triplett, rough and tough on the outside but heart of gold. She has a heart condition but adopts Luke at the start when his parents are killed in a car crash. Yes, it has dark themes but still manages to remain Grimmly hilarious.

It’s huge fun which keeps the adults laughing continually while the kids, I suppose, alternate between cowering in fright and cheering on their peers. The big numbers are all a delight, mostly belters but with what I call ‘comfort lyrics’, wittily predictable rhymes which keep us smiling.

We attended an early preview performance and although all the cast were spot-on exuberant in their roles, some of the tricks and the tech ran less than smoothly. Act one was a joy but Act 2 still needed work and a trim to bring the show to a satisfying finale. By Press Night I’m sure all will be well, and then I would happily see it again and probably give it an extra star. A West End transfer is forecast.

At the end the kids are triumphant (no surprise) but, oddly, they are still mice – cue for all the audience kids to want mice for pets?

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

12/11/23 John R writes –

Coward and Friends

at the Tabard pub theatre, Chiswick

Janie Dee and

Stephan Bednarczyk

Our rating: ★★★

Goup appeal; ★★★

Everyone loves Janie Dee so it was a thrill to anticipate her show at my local pub theatre in Chiswick, which only seats about 90 people. It was a two-person show with the excellent pianist and raconteur Stefan Bednarczyk, who regularly appears at the Crazy Coqs and other London nightspots.

The first surprise was that neither performer used mics, so although in such a tiny space they were not needed for actual volume, the sound to me still needed a bit of a boost. Janie’s voice sounded a bit on the thin side, However we think she might have been battling a cold, plus possibly tired after slogging herself silly in Sondheim’s Old Friends in the West End.

She opened with the Marvellous Party number, which immediately went down well. Her comic timing was also to be admired in many other songs, as was Stefan’s in the more narrative pieces such as The Bar at the Piccolo Marina, The Bronxville Derby and Joan and Don’t put your Daughter on the Stage Mrs Worthington. He also provided some touching readings from Coward’s writings, covering his early stage training and experiences. It was a pity there was no sheet of A4 to identify the sources but it’s a venue with little funding.

Janie opened the second half, rather cheekily, with her current party piece, The Boy from….., referencing some brief accolade for Coward, made by Sondheim in one of his books. But nobody was complaining as it is rather a hoot! They also wittily performed the opening scene from Private Lives, with I’ll See You Again, which then segued into other songs. It did occur to me that perhaps Coward’s strongest talent was his lyric writing, which is delightfully wicked and yet often touching – London Pride for example. She did not sing two of my favourites, If Love Were All and Mad About the Boy.

It was still a most enjoyable afternoon despite a few reservations..

11/11/23 Fredo writes –

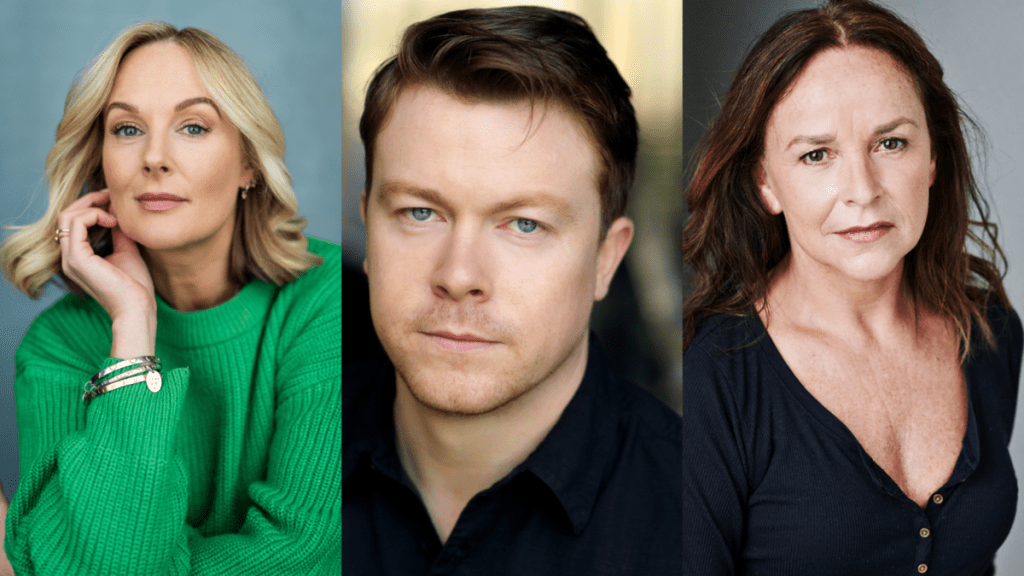

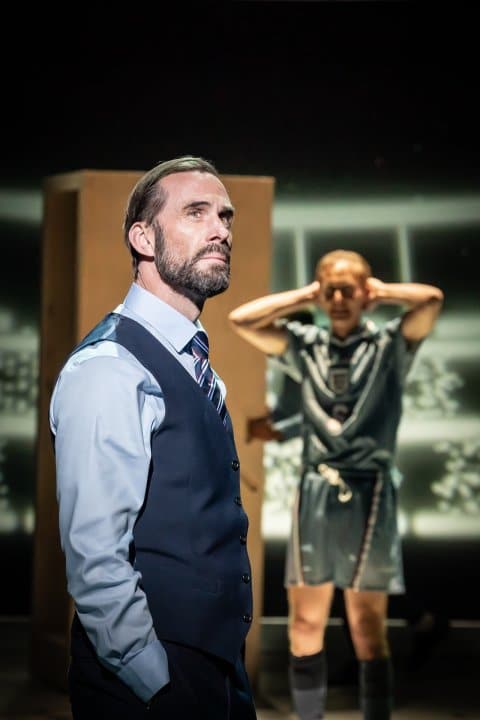

A View from the Bridge

by Arthur Miller, at the Rose Theatre, Kingston

Photos: The Other Richard

Our rating: ★★★

Group appeal: ★★★

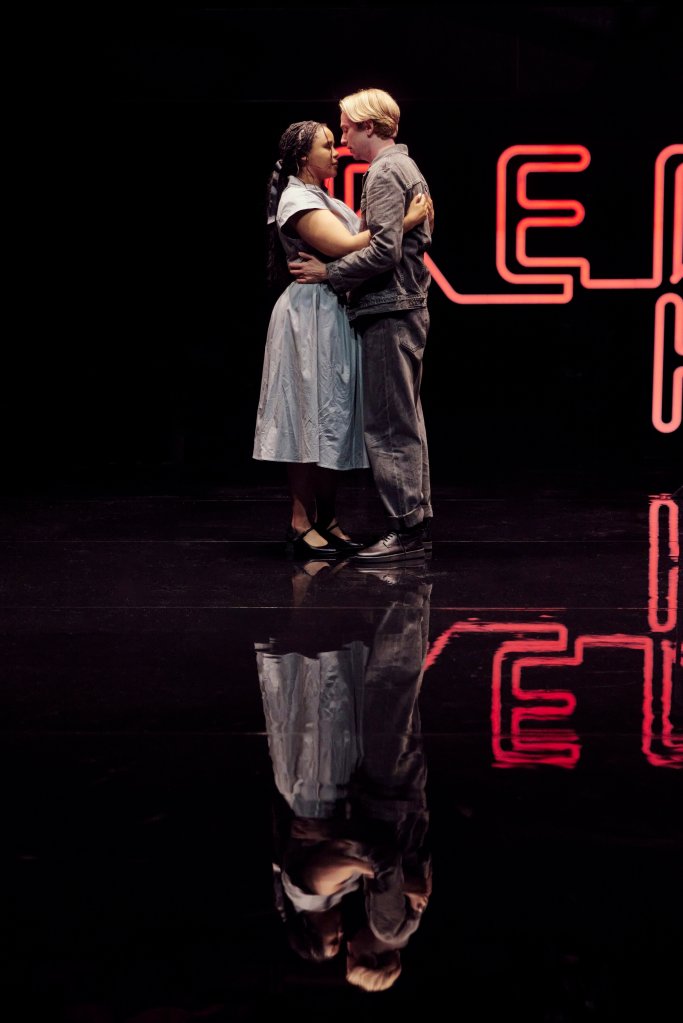

It could be just an ordinary situation: Eddie and his wife Beatrice argue about their adopted niece Catherine taking her first job. But we’ve been warned by the lawyer Mrs Alfieri that it won’t end well. The arrival in the Brooklyn home of Beatrice’s Sicilian cousins, Marco and Rodolfo, as illegal immigrants, upsets the fragile relationships within the cramped household.

Miller’s great play dates from 1955, and still seizes audiences in a longshore-man’s grip. Tension escalates throughout: at the end of the first act, there’s violence bubbling under the unspoken challenge to Eddie of Marco’s presence in his home. There’s more to come as Eddie brutally intervenes in the relationship between Catherine and Rodolfo, and the action moves inexorably to its tragic conclusion.

Johnathan Slinger, who impressed us in David Mamet’s Oleanna, showed Eddie’s suppressed rage and confused love for Catherine. His towering performance was matched by Kirsty Bushell’s Beatrice and her confusion as the events around her slip out of control. I thought that Rachelle Diedericks started too young as Catherine, but she became more convincing in the course of the play and, as Rodolfo, Luke Newberry was both endearing, and believable as a mild man whose presence would enrage Eddie.

I’ve seen this play many times, and in some tremendous productions. The bar is high, and sadly this one wasn’t one of the best. The director Holly Race Roughan made some bizarre decisions: at crucial moments, one of the longshore-men becomes a ballet dancer; there’s a central swing on stage (in a home in Brooklyn?) and although we’re reminded several times that the apartment is on the ground floor, the actors have to descend a staircase from what is supposed to be street level. A chair placed front-stage intruded on the difficult sightlines in this theatre. And the floor reflecting a neon RED HOOK sign does not assist the intimate scenes.

I have no quarrel with cross gender-casting (well, not always) but casting a woman in the role of the lawyer Alfieri was a mistake. First of all, it seemed unlikely that a man like Eddie would seek advice from a woman. And good actress though we know her to be, Nancy Crane didn’t convey the poetry of Alfieri’s narration; in particular, her voice was too light to give the necessary resonance to the epitaph at the play’s end.

Nevertheless, this drama has devastating impact. Eddie Carbone, the appropriately named burnt-out man, stands with Miller’s other self-deluded heroes Willy Loman in Death of a Saleman and Joe Keller in All My Sons. Arthur Miller is the laureate of the overlooked, and raises the tragedies of ordinary people to epic proportions. Despite the flaws in this production, I still felt elevated by it.

07/11/23 Fredo writes –

Portia Coughlan

by Marina Carr, at the Almeida Theatre

It’s 10 o’clock on the morning of Portia’s 30th birthday. She’s pouring herself a drink, and it’s not her first. It’s not a celebration either, as it’s the 15th anniversary of the death of her twin brother. “It’s not easy being married to Portia Coughlan,” commented her creator Marina Carr, and it’s not much easier being in the audience either. “I’m traumatised. We’re all traumatised,” commented one woman to an attendant as we left the theatre.

There’s little evidence of the Celtic Tiger in this deprived rural community in Ireland in 1996, though Portia’s unfortunate husband is the wealthiest man in town. Portia herself embodies discontent and despair like Hedda Gabler, but with more appetite for destruction . All her family are relentlessly at each others’ throats, as they claw over old arguments and resentments (Sorcha Cusack and Mairead McKinley give lessons in venom-spitting with every line they utter). Hints of incest twist through the generations, and it’s clearly heading for a tragic end.

Do we care? Surprisingly, my interest was held throughout. Marina Carr has a gift for writing dialogue that segues easily from invective to lyrical (methinks she studied J M Synge at some point) and she spikes the diatribes with shafts of dark humour. At the end of the first act, we are suddenly propelled to the end of the play, and the second act covers the events that lead to the devastating climax. This didn’t work for me, and I suspect some authorial/director revision may have taken place. The songs by Maimuna Memon were beautiful, and beautifully sung by Archee Aitch Wylie, but seemed to work against the grain of the play.

Rising star Alison Oliver rises to the challenge of this merciless Portia; she brings much-needed warmth and sympathy in her performance. Even in the extraordinary scene when she lashes out at her inoffensive husband, revealing her loathing, she still makes us understand the depth of Portia’s anguish. She was rightly acclaimed by the audience, and seemed unsure about taking a solo bow. She had certainly earned the applause.

Our rating: ★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

05/11/23 Mike writes –

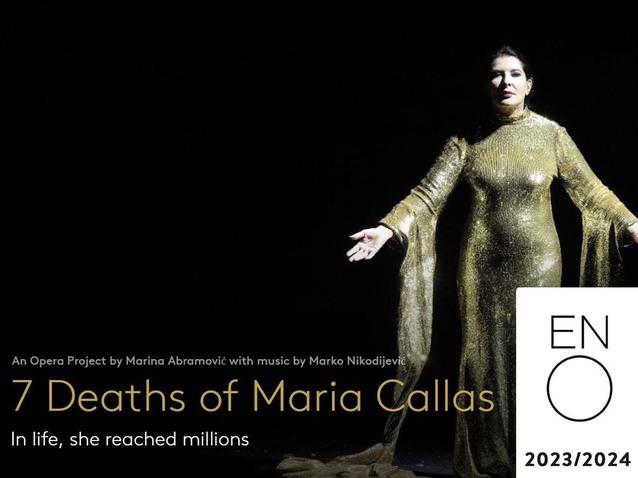

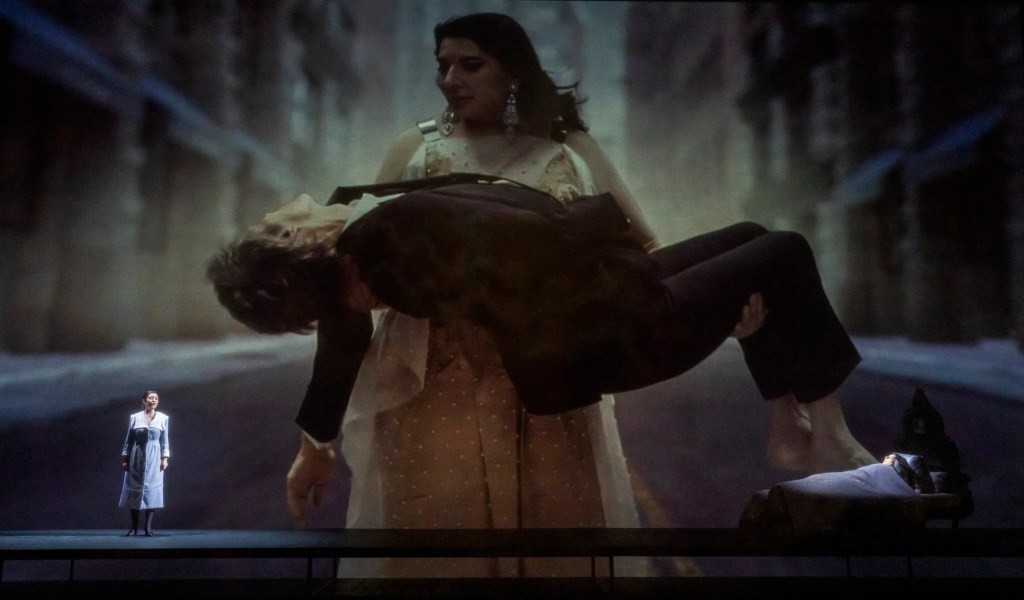

7 Deaths of Maria Callas

an opera project by Marina Abramović , at the London Coliseum (Dress rehearsal)

Photos: : Tristram Kenton

Something rather amazing and uncharacteristic is happening at the Coliseum. And that is just what it is – a happening, not quite an opera and not quite an installation, but ‘an opera project’ . It comes from the performance artist Marina Abramović who currently also has an exhibition of her works at the Royal Academy – video, sculpture, installation, and re-enactment. But for now she is installed on stage herself for 6 performances in this tribute to Maria Callas.

Marina plays Maria, looking very like her (though a little fuller-figured) and is on-stage almost throughout…playing dead. She lies in bed in a spotlight while seven deaths that Maria performed in her operas are re-enacted on film; the surreal sequences are performed in fantastical fashion by Marina and Willem Defoe on a vast screen behind her bed. A voice-over intones interpretations of each death, a jump from a skyscraper representing Tosca and strangulation by a snake referencing Othello, etc.

However, this is an opera project so the voice of Callas is acknowledged by live performances of 7 of her most famous operatic arias – the two operas mentioned previously plus Madama Butterfly, Carmen, Lucia di Lammermoor, La Traviata and Norma. Move over Maria, while 7 singers do her more than fair homage in impressive and very moving performances sung direct to the audience with a full orchestral accompaniment. They all deserve a mention – Sarah Tynan, Elbenita Kajtazi, Nadine Benjamin, Eri Nakamura, Aigul Akhmetshina, Karah Son and Sophie Bevan.

I’m a sucker for a ‘coup de théatre’ and, just when something special is needed to finish this rather sombre and serious contemplation of death, comes a complete change in presentation. It’s the perfect theatrical scene to put to rest a diva, a career, a legend, and of course this unique happening. Finally Marina appears centre stage as Callas, in a signature gold and glistening evening dress, to showcase a recording of the diva’s voice singing Casta Diva from Norma.

The whole event is surprisingly emotional, the arias are gloriously performed, and the concept is intriguing, involving and highly collectible for anyone with any interest in Maria Callas. Or, new to me, in Marina Abramović.

I have to confess that I was far more impressed than Fredo who found Ms Abramovic’s contributions a bit pretentious but enjoyed the singing and the orchestra. I loved ‘the project’ and admired it for its originality and for the high quality of its presentation and performance.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★

20/10/23 Mike writes –

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

by Joel Horwood, from the novel by Neil Gaiman, at the Noel Coward Theatre

Photos: Manuel Harlan

I must show my hand here – we were invited down the Lane by DelMack and I have an aversion to Fantasy Fiction. The ocean at the end of this lane is a pond on a farm, fantasised into a world of monsters with an aggressive agenda, and a ‘make it up as you go along’ story to keep kids enthralled. There was a lack of kids in the audience but many youngish adults seemed keen to go along for the ride. And, I must admit, a very theatrical ride it was too.

There’s another term to set my teeth on edge – Magical Realism. The plot is in that realm, and is based on a 2013 book in which a Man returns to his childhood home to rekindle memories of (cliché warning) a nasty stepmother with uncanny abilities to send him into panics of persecution. There was a girlfriend and her know-all granny on hand back then, with magical abilities to fight evil spirits, create safe spaces in fairy rings, explain the supernatural…and all before nipping off to Australia (don’t ask).

Forget trying to follow the fantastical plot – your effort would be wasted. The writing references Narnia, the Hobbit, Peter Pan, Harry Potter, etc etc, to give itself a validating edge, but it’s the theatrics which grab at our attention. War Horse, Pi, and other puppetry exercises set the style of presentation – we soon forget to notice the balletic manipulators and succumb to the bombardment by soundscape, movement and dramatic lighting, which create monstrous diversions and terrors.

But I have to warn you, there’s a wearisome amount of explanatory verbiage which drags the plot along at a very slow pace. The novelty of the presentation wore off during Act 1 so by Act 2 the tedium was beyond my comprehension and patience.

On the plus side (yes, there is a plus side) the effects were created slickly with imagination, and surprisingly with no resort to fashionable projections. Daniel Cornish lead the cast energetically as Boy, and it was good to find Charlie Brooks (forever an EastEnders’ bad girl) as stepmother Ursula. She was used amusingly in an illusion, disappearing through multiple doors and reappearing impossibly on another part of the stage. That was a highlight for me, along with the appearance of a shape-changing demon. Most of the rest was a snooze fest.

Incredibly, this production has received many 4 and 5 ★ reviews from critics more easily impressed than me.

Our rating: ★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

12/10/23 Kathie writes –

It’s Headed Straight Towards Us

by Adrian Edmondson and Nigel Planer, at the Park Theatre

Photos: Pamela Raith

Written by Adrian Edmondson and Nigel Planer, there was, inevitably, a comic element to this play, but it had a broader remit. The setting is a trailer being used by an actor on a film set, being shot on the Gígjökull Glacier in Iceland, which sits on a volcano. The film is Vulcan 7, with a monster/sci-fi theme, and the latest in a series, all of which have a character played by Hugh Delavois (Samuel West). For this film, the actor Gary Savage (Rufus Hound) is joining the cast to play an ‘Angry Thermidon’. Hugh and Gary have known each other since drama school and have had, we soon find out, a turbulent history. The final member of the cast is Leela Vitoli (Nenda Neururer) who is the Production Runner with the challenging task of getting things to happen, and dealing with the fragile egos of these particular actors occupies much of her time and energy.

The comparison between the careers of our 2 fictional actors is revealed through a litany of parts they had in plays or films (all ones known to regular theatre/film-goers), with frequent mention of other real-life actors (Daniel Day-Lewis is often referenced enviously!) . While Gary is now reduced to playing a heavily costumed monster, with just one word to deliver, he has had the more illustrious career which has gradually dwindled through his drinking and inappropriate behaviour. Hugh has had a steadier but less prominent past and despite their apparent antipathy they both have their inner demons which emerge more fully when external events shake things up. The bit of the snowy glacier, upon which their trailer sits, is calved off from the rest through some volcanic/earthquake activity and their safety is uncertain. What will become of them all as natural forces threaten?

In Samuel West and Rufus Hound we were assured of good performances and Nenda Neururer held her own. The rapid-fire delivery of the text and frequent physical stunts kept the pace at just less than frantic, and we were certainly entertained, not least by the sense of an insider’s view of the world of acting. The stage had been mounted so as to shake and shudder with the earth tremors which was very well done, especially for such a small theatre space.

Our rating: ★★★

plus another ★ for the special effects.

Group appeal: ★★★

05/10/23 Fredo writes –

Shooting Hedda Gabler

by Nina Segal after Henrik Ibsen, at the Rose Theatre, Kingston

Photos: Andy Paradise

They rolled out the red carpet at the Rose Theatre, not for us but for the world premiere performance of their co-production with Norway’s Ibsen Theatre. This new play daringly references Ibsen’s masterpiece, and the playful title indicates that we’ll have to put our fingers in our ears before it ends.

An unnamed American screen star – let’s call her ‘Hedda’ – arrives in Oslo to film Hedda Gabler. Her career is on the slide, there are rumours of drink and drugs (though she insists she’s clean and sober) and her agent won’t pick up her calls. Her life is a mess: there’s been a recent scandal in the gossip columns, gleefully mentioned by her co-star Jorgen (Joshua James). Later, a message to her lover telling him that she is pregnant gets the response, “Don’t contact me again.”

‘Hedda’s’ initial unease increases as shooting starts. The film director Henrik (Norwegian actor Christian Rubeck in commanding form) is a bully and possible sexual predator – and he’s cast her former lover (played by Avi Nash) as Hedda’s former lover. There’s no film script, and a hostile co-star (Matilda Bailes) is also the on-set therapist and intimacy co-ordinator, a reference to current performance obsessions. The sympathetic assistant director (Anna Andresen) offers support but she too is cowed by Henrik.

Antonia Thomas anchors the play with her vivid depiction of ‘Hedda’s’ discomfort which mounts as the play progresses. She charts ‘Hedda’s’ isolation and disorientation as the plot of the play and its characters get closer to the events in Ibsen’s drama. It doesn’t end well.

There is some humour in the early scenes, but neither playwright Nina Segal nor director Jeff James find a consistent tone as the play unfolds. James has to wrestle with the huge and largely inhospitable space of the Rose stage. I could detect the influence of Dutch director Ivo von Hove (and not in a good way) in his positioning of key scenes in isolated areas of the vast space. And he diluted the impact of the play’s final scenes by having the actors appear in “green screen” attire.

Segal creates a problem for herself in cleaving so closely to Ibsen, and always inviting inevitable comparisons. As a riff on Hedda Gabler, it doesn’t really work. And yet that is the play’s purpose. Those unfamiliar with Ibsen’s play will be disadvantaged.

The interest of the play lives in the tension between the actress and the director, and it was at its best when Antonia Thomas and Christian Rubeck could flex their muscles. In fact, all the actors seized their opportunities, though I felt that the gifted Joshua James was seriously under-used. Nevertheless, his mother, West End star Lia Williams, looked proud and radiant in the foyer after the show.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

29/09/23 Mike writes

Mrs Doubtfire

Book by John O’Farrell and Karey Kirkpatrick and music and lyrics by Tony Award-winning duo Wayne Kirkpatrick and Karey Kirkpatrick, at the Shaftesbury Theatre.

Gabriel Vick / Mrs Doubtfire

She was Madame Doubtfire, a book for children back in 1983, then Robin Williams played her as Mrs Doubtfire in the 1993 movie. Now she has come to the West End stage via Broadway in a slick new comedy-musical, very American and very much aimed at those who may remember the film.

Frankly, we had little interest in seeing the show, until we were invited by our friends at DelMack so went along to see exactly who this Mrs Doubtfire is. No cast names had been mentioned, just a picture of Mrs D on the posters, so what we really wanted to know was who plays the lead that the producers don’t want to publicise, unrecognisable as the lady herself in the ads, disguised by fat-suit and prosthetic mask. Only last month Fredo wrote about shows without stars, sold on their title alone, like Les Mis, Moulin Rouge and Phantom. Now we have seen the show, we want to shout about Gabriel Vick, the unknown star who transforms himself into this Scottish down-to-earth children’s Nanny.

He is just amazing, a likeable presence on stage whose performance and personality carry the show. He is a good-looking old-pro at both musicals and plays (Once, Avenue Q, Cabaret, La Cage Aux Folles, The Tempest, Murder in the Cathedral…) but he has never made it to star billing. He still hasn’t, but he certainly should!

He plays a fun Dad, an out-of-work entertainer, who loves his kids but cannot keep a job. He’s up against a practical and professional Mum – she divorces him and advertises for a Nanny to look after the kids. You can guess the rest. The show settles into a cross between Mary Poppins and Tootsie, with Kramer v Kramer thickening the plot. Of course everyone learns lessons about family ties, responsibility, deception, and naturally love, all mixed together with lively humour. There’s even a song called As Long As There Is Love.

It’s a handsome production with familiar character types and smart sets. But it’s Gabriel Vick who holds it all together, has us rooting for him, and manages on-stage quick-changes from Dad to Nanny in seconds, while disappearing through one door to reappear through another. Part of the entertainment here is seeing him change or we just may not believe it’s the same person.

Part panto and part standard musical fare with some cringe-making humourous moments, it gains class by its production values and well-chosen casting. The audience seemed older than for the currently popular juke-box musicals, with a few families bringing young children – they were all amused and entertained, but it was Vick who brought everyone to their feet at the curtain call. Deservedly so.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

26/09/23 Kathie writes –

Orlando furioso

Musica di Antonio Vivaldi, libretto di Grazio Braccioli, at the Teatro Malibran, Venice.

Today, if Vivaldi is mentioned it is The Four Seasons, plus a concerto or two, that readily come to mind and yet there are 50 operas that have been identified as being by him, of which only 20 survive and from those just 16 in a complete form. Seldom performed, the chance to see Orlando Furioso while in Venice for Mike’s 80th birthday celebration was an opportunity not to be missed.

First performed in Venice in 1727, the libretto was based on the 1516 epic poem Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto which had earlier roots in other poems. The story of Orlando, a knight-errant and supposedly a nephew of Charlemagne, was used on other occasions by Vivaldi and also by Handel, who wrote 3 operas based upon this heroic tale.

The orchestra and chorus of La Fenice were joined by a fairly small cast where the male and female roles were somewhat blurred by having females playing most of the male roles, possibly in lieu of the castrati of the day. The complete opera comes in at 4 hours but here we had the 3-hour version, performed in Italian, of course, with Italian surtitles. It’s fair to say that we were not always entirely clear about the storyline!

The plot sees us on the island of the enchantress Alcina. Her magical powers come from the ashes of Merlin (a surprise to us that he popped up here) and she is trying to stop Orlando from interfering in a match between Angelica and Medoro. Orlando is in love with Angelica. Other characters include Ruggiero who arrives on a flying horse (though in this version it was a creature with a beak) who is on team Orlando but who is seduced by Alcina. Bradamante, the beloved of Ruggiero, is not happy. Orlando eventually destroys Alcina’s powers and some sort of reconciliation is achieved.

The music, musicianship and vocal dexterity cannot be faulted. Where we were disappointed was in the staging and the continuity. It had a clumsiness to it which reduced the experience to less than it might have been.

Our ratings:

For the chance to have seen it: ★★★★

In the execution: ★★

Mike adds: Opera seats are always expensive so we bought tickets for the Gallery, far from ideal. The theatre lacks atmosphere, lots of cream paint, and the sightlines are poor. The gallery was not full (we couldn’t see the size of the audience below) so several people changed their seats to get a better view. We did too, and eventually settled with a clear but very distant view of the stage. The acoustics were excellent, both orchestra and voices, but this meant stage movements were loud too, footsteps accentuated. And from our high view, we could see stagehands moving props and bending to try to hide themselves. Too many distractions! For many €uros more, from a better seat, we may have enjoyed it more.

09/09/23 Mike writes –

A Mirror

by Sam Holcroft, at the Almeida Theatre

Photos: Marc Brenner

Sam Holcroft reportedly brought the idea for this play back from her holiday jaunt to North Korea. I hope she had a better time than she gives us. It begins well. We are guests at a wedding ceremony in a dictatorial state where culture is repressively controlled. But the wedding is bogus, a front for performing a play that would otherwise be banned. This forbidden play is all about censoring a play because it is based on unacceptable overheard verbatim conversation, so the playwright (the bogus wedding’s husband) writes another based on his confrontation with the culture minister. At this point you may not be following me, but the talented cast bring it off in an entertaining way, wheels turning within wheels.

But half way through, this merry whirl comes off its own wheels. We get embroiled in yet another play about a wartime incident and, even with an interruption when this bogus event is stopped by security police and we have to pretend to be wedding guests again, I never returned to caring what is really happening.

I tried to imagine the despicable Nadine Dorries controlling our own cultural efforts when she was a minister for culture, but the more the playwright tried to create relevance (mirroring real life, you might say) the more my hold on events slipped away.

With each cast member ‘being’ at least one person who is pretending to be another, the actors deserve praise for entertaining us as well as they do. There was much amusement in the play’s first half (two hours, no interval) but as a more serious theme surfaced, fascism v. cultural freedom, the complications became wearisome.

But there were pleasures. The Almeida had been transformed into a convincing marriage registry office with flowers, a podium, curtains, wedding seating, and we all entered into the spirit of the enterprise. Jonny Lee Miller was the bogus registrar/culture minister manipulating our deception, and Tanya Reynolds managed her nervous but ultimately assertive character appealingly. Micheal Ward and Geoffrey Streatfield were the two contrasting playwrights.

At the end, and here’s a Spoiler Alert, we are all arrested for watching such a subversive event. If only that had been so. However, it whetted my appetite for a holiday in North Korea, however briefly, but of course no chance of the play being performed there. The Almeida pulled out the stops to give it a chance (The Guardian, of course, and many other papers were impressed) so I hope some had a better time than we did. Maybe the cheers were for the politics rather than the play.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★

25/08/23 Mike writes –

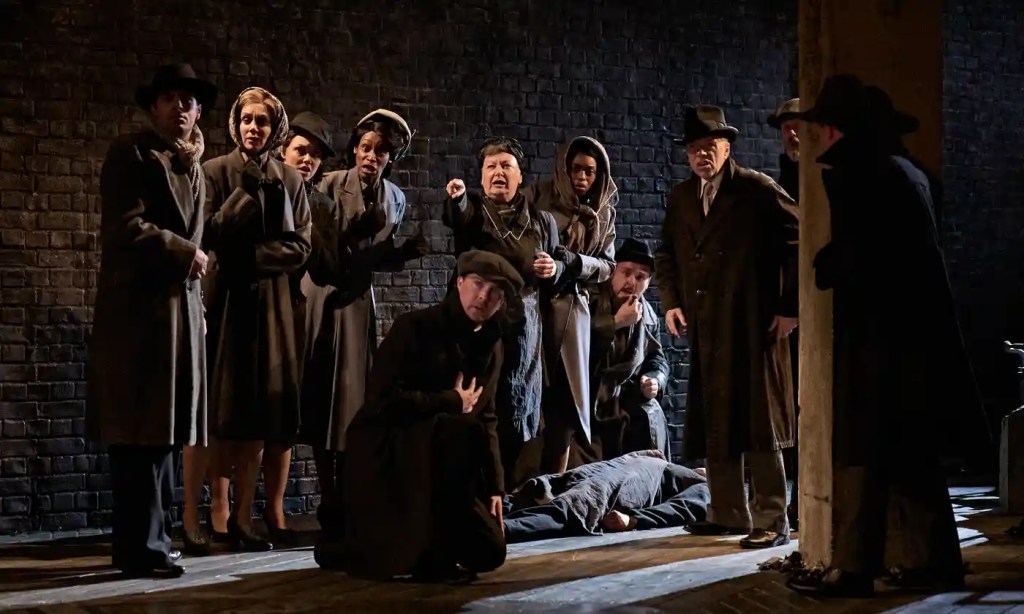

The Third Man

A Musical Thriller, Book by Christopher Hampton, Lyrics by Don Black, Music by George Fenton, at the Menier Chocolate Factory.

Harry has history, at least in the minds of my generation. That Harry Lime theme on zither has wormed its way into our subconscious, and we remember Orson Wells filling the screen as the illusive Harry himself. There were also Joseph Cotton, Alida Valli and Trevor Howard – classic movie, classic cast. I can still see that ferris wheel too. Then of course there’s Graham Greene’s novel. All this may be a selling point for the musical, but also a reputation to live up to. It’s brave to try.

The musical makers also have reputations. It was Don Black & Christopher Hampton (Book and Lyrics), Trevor Nunn as Director, and Jason Carr as Orchestrator who lured us to the Menier, as well as the theatre’s adventurous reputation for producing musicals. Did it earn a reputation of it’s own? Certainly it did with our next-generation-down companions who, not knowing the original film or book, thought it “absolutely marvellous”. They then bought the DVD.

For us it still looked like a ‘work in progress’, sparsely produced and hampered by being gloomily set mostly in dark alleys and the sewers, with grey always being the dominant colour – appropriately ’film noir’, I suppose. However, it did have a cast of 19 and an orchestra of 9, so that’s where the budget went. I commented before the show that we mustn’t expect tap-dancing, but a brief cabaret scene was included that was no competition for Cabaret.

With the audience on three sides, there was still plenty of space for moving the cast around, rushing hither and thither, and grouping threateningly. The songs, more scene-stoppers than scene-setters, were….oh, I can’t remember any, and they are not listed in the programme. The music just occasionally hinted at that Harry Lime theme tune. The ferris wheel did make an appearance, as just a swinging platform (disappointing), and the chase through the sewers down a spiral ladder (unused!) hardly got one’s pulse racing (again disappointing).

On the plus side was Sam Underwood in the lead role of Holly Martins. He pulled the show together with an energetic and commanding performance, hardly ever off stage, the perfect gumshoe. Simon Bailey as Harry Lime appears late in the show but adds a stylish presence. Natalie Dunn as Anna Schmitt was not well cast, lacking the charisma for a romantic interest – when she spat in Holly’s face at the end it was more of a relief than a shock.

But there was enough of interest in the story and atmosphere to hold attention, enough bones on which to flesh out a better show, enough hope for a success after a make-over. Harry may well live again.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★½

Photos: Manuel Harlan

15/08/23 Kathie writes –

Spiral

by Abigail Hood, at the Jermyn Street Theatre

A play first performed at the Park Theatre in 2018 returns to the stage in the very compact Jermyn Street Theatre. The cast of 4 comprises husband and wife, Tom and Gill, plus Mark and Leah who are in a relationship which, we soon learn, is not a healthy one.

Tom & Gill, both school teachers, have a 15 year old daughter, Sophie, who has disappeared after having been dropped off by Tom to go to her school. A few months later Tom meets up with Leah who he has hired to look, talk and behave like his missing daughter. Tom’s association with Leah is discovered by his wife and Mark, who acts as Leah’s handler for this and other role-playing jobs, assumes she has sex with her clients which leads him to abuse her, verbally, physically and sexually. It is clear that this happens frequently.

After comforting one of his pupils Tom is told she has accused him of touching her inappropriately which then opens him up to questions about his relationship with his daughter and his role in her disappearance. He has continued to see Leah, out of friendship and concern he tries to assure his wife, but both she and Mark question his motives and life is looking very bleak for everyone, except Mark who deserves no sympathy.

There are further twists and turns and we, the audience, are left wondering until the end what sort of man Tom is and how much we can trust what he says. Whilst not every situation is resolved there is a conclusion of a sort which provides some satisfaction.

The play was written by Abigail Hood (Leah) and directed by Kevin Tomlinson (Mark). They were joined by Jasper Jacob (Tom) and Rebecca Crankshaw (Gill) and this small cast made a mighty impact in the tiny space dealing with challenging issues where the emotions and underlying tensions were all too exposed. Not always comfortable to watch but certainly worth seeing.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★

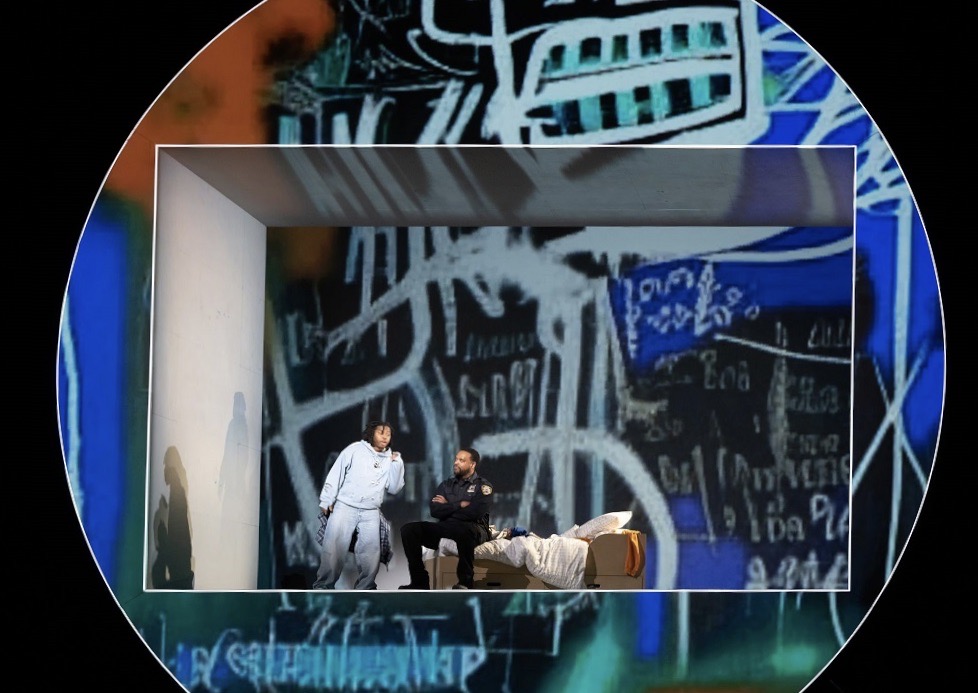

11/08/23 Mike writes –

The Effect

by Lucy Prebble at the National: Lyttelton Theatre

Sometimes presentation is all. Director Jamie Lloyd finds himself at the National Theatre with all its resources at his disposal so he goes big and bold with The Effect. We saw this play back in 2012 with Billie Piper and Jonjo O’Neill at the Cottesloe. It now returns, installed in a reconfigured Lyttelton with an all-black cast, revised and updated for a new decade. It now has a traverse stage brought forward into the front Stalls with seating raised up to the front of the Circle and another bank of seating in the old stage area. The stage is lit dramatically from all sides with its floor lit from beneath in changing geometric shapes. The cast of just four up their game to suit this forensic focus. I wondered just how much it all cost and, more essentially, whether it was worth it.

We paid only £20 to sit in the back row of the stage seating, but there were many top price empty seats and it was our lucky day to be moved forward into the vacant seats. We were grateful as, despite the big staging, this is an intimate drama with emotions in the spotlight.

(Click on photos to enlarge)

The two younger characters are partaking in an antidepressant drugs trial, observed by two clinicians. One is asked if she feels sad. Or depressed? Is there a difference? As the doses increase, feelings become more acute and the friendship between Tristan (Paapa Essiedu) and Connie (Taylor Russell) becomes more combative as they realise they are falling in love. But is it real, or just the result of the increasing drug doses? Are any mental health issues being inflamed or surpressed, and whose feelings are real feelings? Does it make a difference if one of them is being given only a placebo? And are the observers (Michele Austin and Kobna Holdbrook-Smith), confrontationally placed, being objective or just reacting according to their own previous emotional history?

This is all very involving for the audience, reacting with some laughter and some concerned shock of recognition, especially as the tone becomes more intense. We are led down thoughtful paths. And of course the ethics of human drug testing is always there for us to consider.

But (and that But was never far from my mind) I did wonder if all this was as deep as it liked to think it was. I was reminded perhaps of the movies Love Potion (a horror flick from 1987) or Love Potion No.9 (a song and a romcom from the 1990s) or any variation on that genre. And of course the songs about love are numerous and timeless – Love Changes Everything, Love Makes the World Go Round, etc etc etc. Lucie Prebble’s play approaches the subject from a different angle but does it dig deeper and raise different concerns?

The performers themselves, battling it out in the ring, probably answered that question with an emphatic Yes. I was not so sure. The four actors were impressive – committed, persuasive and natural. That OTT staging, so simple and yet so affecting, added considerably to our positive response and to the audience’s standing ovation for the wrung-out actors at the end. If I remember rightly, it was more powerful now than it was back then. We certainly had our £20’s worth sitting in £89 seats!

Our rating: ★ ★ ★★ / Group appeal: ★ ★ ★ ½

Photos: Marc Brenner (2023) & Alastair Muir (2012)

08/08/23 Fredo writes –

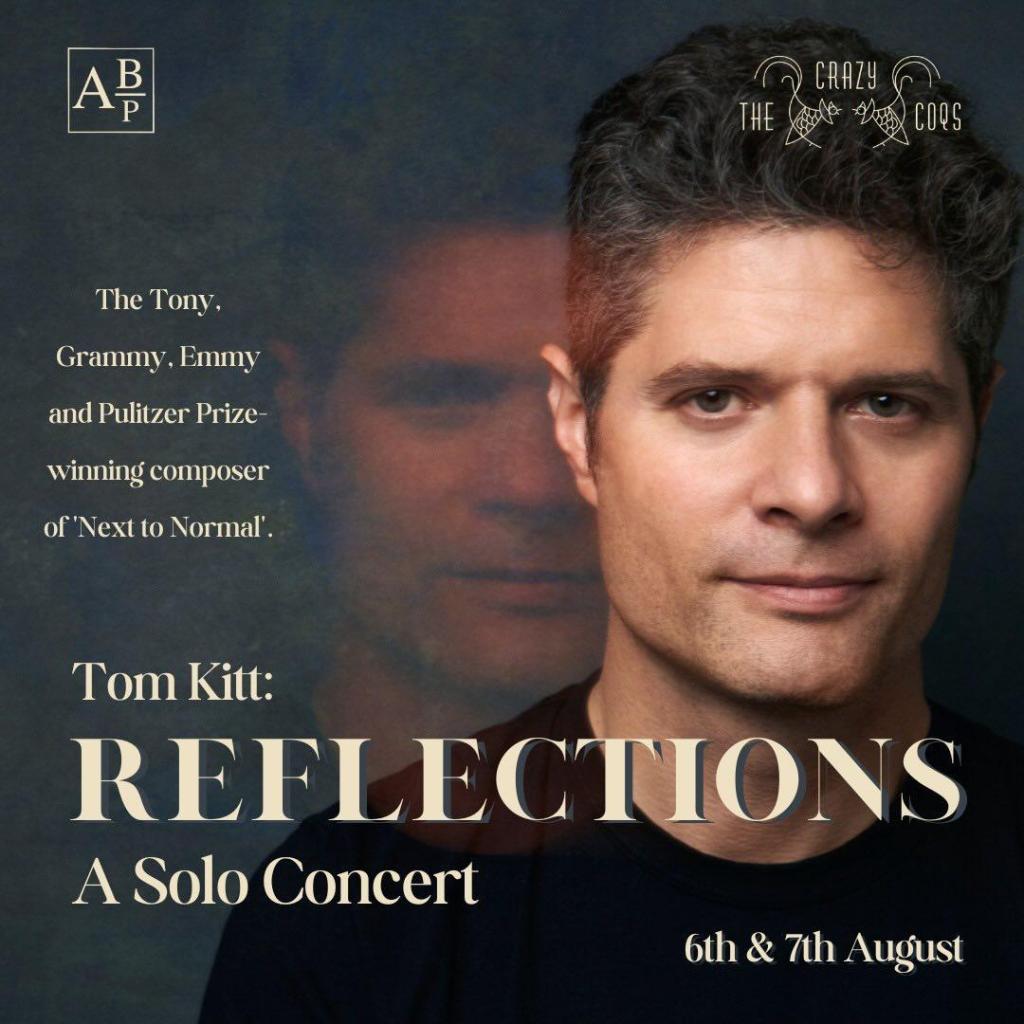

Tom Kitt: Reflections

A cabaret performance at The Crazy Coqs

Composer, pianist and singer Tom Kitt is almost famous in this country (and by the way, that’s the title of one of his shows). Although his work has been presented 9 or 10 times on Broadway, and won many awards and prizes, he’s had little exposure over here. That is about to change: he has written the additional music for The SpongeBob Musical, currently showing at the South Bank Centre, and has just completed a short cabaret season at Crazy Coqs. Most significantly, his most successful musical, next to normal, starts previews at the Donmar on 14 August.

The personable and handsome Mr Kitt gave us a preview of some of the songs from this show, but first he treated us to a sample of tunes from several of his other successes and near-misses. These include Almost Famous, Flying Over Sunset, Freaky Friday and If/Then (one could identify recurring themes of mother/child relationships and alternative realities and, talking about himself, he often mentioned his wife and family). It’s always difficult to judge how a song works in a show when you hear it out of context, but Tom played and sang with passion and commitment. (Here’s a LINK to Lost in New York City from Almost Famous.)

He has a good voice, but when he introduced West End star Kerry Ellis to sing a song from If/Then, the performance ignited. Kerry inhabited the song, and made us realise that it was part of a drama, not just another number. This happened again, in the section of the performance devoted to next to normal. Tom had brought along members of the Donmar cast, and the performances by Caissie Levy, Jack Wolfe and Eleanor Worthington-Cox were electrifying.

Caissie Levy is a respected performer on Broadway, having appeared in Les Miserables and Wicked, and in London in Ghost. She had previously worked with Michael Longhurst in Caroline, or Change on Broadway. It will be a memorable experience to hear her sing the emotional I Miss the Mountains from next to normal on the Donmar stage.

(Here’s a LINK.)

Michael, the Artistic Director of the Donmar, had told us that he was moved to tears by Jack Wolfe’s audition. This young man is a remarkable performer presenting a youthful fragility (he’s 27) and has clearly mastered the songs he has to sing.

Another star is about to be born in the person of Eleanor Worthington-Cox. She has a lovely voice too (and the tiniest waist I’ve ever seen!). A trigger warning: the duet between Caissie and Eleanor near the end of the show will have you fumbling for your Kleenex; come prepared.

(Here’s a LINK.)

The run of next to normal is sold out at the Donmar – I know because people near us were searching for tickets on their phones. If you haven’t booked, let me know and I’ll add you to the waiting-list for our visit on 29 August.

These performers were rightly applauded, but it was Tom Kitt’s evening. He’s having a London moment. Almost famous? He will be soon!

Our rating: ★ ★ ★★ / Group appeal: ★ ★ ★ ★

08/07/23 Mike writes –

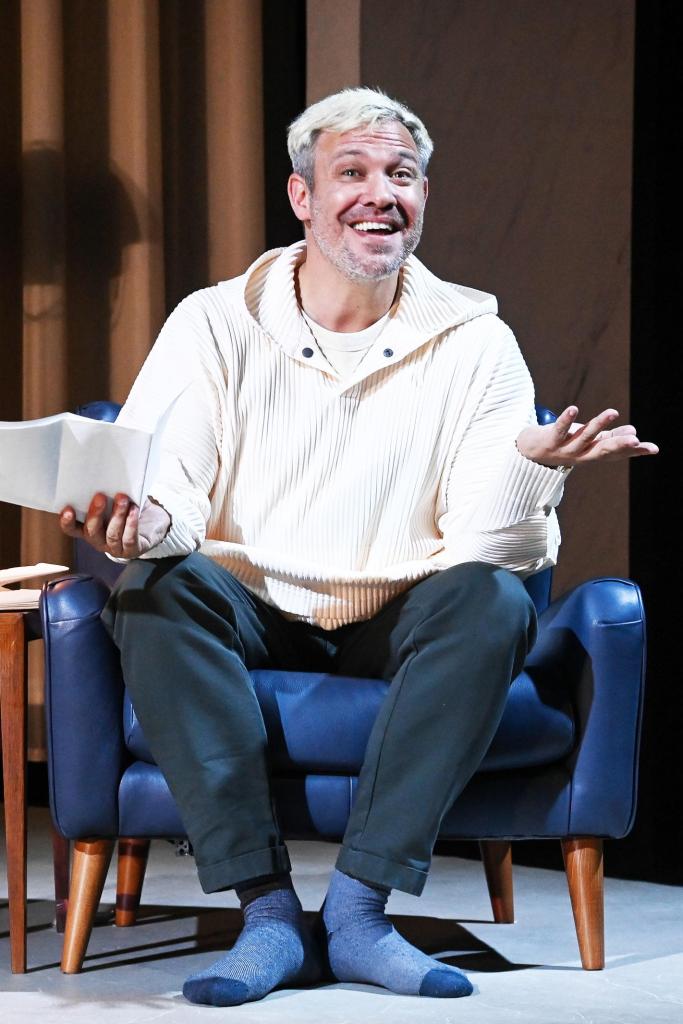

Song from Far Away

by Simon Stephens and Mark Eitzel, at Hampstead Theatre

What’s it about? Willem is called back from New York to the family home in Amsterdam where his brother has died. He mulls over his circumstances, his grief, the differences between his and his brother’s life, and what the future may hold.

What does it have going for it? Will Young giving a monologue written by Simon Stephens, author of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime. It has one song too, by Mark Eitzel.

Did we enjoy it? Will Young was our draw although we are not fans, we just wanted to see if he could do it after mysteriously withdrawing from Strictly a few years back. He is older now, white-blond and paunchy yet still with a youthful manner. The part of a camp and gay New Yorker suited him and his performance impressed. He brought life and understanding to the script (his own brother died three years ago) talking easily to his audience in a relaxed manner, bringing as much restrained emotion as the part required.

But he could not overcome the bland predictability that the writing gave him – letter reading, family differences, a hotel one-night-stand, his regrets – I wanted more grit, more feeling, to keep me interested (and awake). His softly soothing voice hardly reached the rear Stalls, but when, at last, the monologue segued into song it became more obvious why Young was perfect casting, a perfect voice still. But he should have been given more to offer us.

Hampstead had generously provided curtains, a couch, a coffee table (a little reminiscent of a Parkie talk-show set) and oddly a ceiling which went up and down expensively without reason. Willem’s hair matched the decor, even his baggy designer hoodie was colour coordinated with the furnishings, so all was of a piece and I rather wished something could have broken the spell. Just a little drama would have helped, maybe spilled red wine on the oatmeal carpet.

Our rating: ★ ★ ★ Group appeal: ★ ★ ★

07/07/23 Fredo writes –

Dear England

A new play by James Graham, at the National: Olivier Theatre

HE SHOOTS! HE SCORES! I’m talking about James Graham here. And Joseph Fiennes too. Full disclosure: I’ve never been to a football match in my life. And I can’t foresee a future where I’ll be on the terraces, cheering my team. Even so, I was hooked on Dear England from the opening moment when Gareth Southgate lines up to take that fateful penalty – and misses. James Graham’s thrilling play fast-forwards to Southgate taking over the management of the England team, and the subsequent progress through to the Qatari World Cup. It’s a turbulent period, as Southgate reshapes the team and introduces new tactics. There’s resistance from both team and management, there are failures, and in the end there is pride not in victory but in achievement.

It’s a spectacular show, anchored by the performance of Joseph Fiennes as Southgate. First of all, he looks more like Gareth Southgate than he looks like Joseph Fiennes, and he has the same soft yet slightly high-pitched voice plus the body language. In a week where we had already witnessed Will Keen’s eerily life-like performance of Putin in Patriots, this was another performance that seemed to capture the essence of the man. This too went beyond mere impersonation; Fiennes portrayed a man making reparation for a past failure, while embodying a sense of fair play and decency. His scenes with sports psychologist Pippa Grange (Gina McKee, in typically intelligent, sensitive mode) add nuance to a narrative that might seem testosterone-heavy.

Graham links the England’s team success with a sense of national pride. Without overstating his case, he shows how the country’s self-image is represented by its sporting heroes. It’s an epic play, and Graham and director Rupert Goold exercise firm control over the many tones of voice employed to tell the story. Southgate is diffident and refreshingly free of bombast – and there’s plenty of that from John Hodgkinson, Paul Thornley and Sean Gilder as assorted managers and trainers. Meanwhile, the action is punctuated by commentary from Gary Lineker (who else?) in one of a series of caricatures (that includes Sven-Goran Erikson, Boris Johnson, Wayne Rooney, Alex Scott and Theresa May) supplied by Gunnar Cauthery and Crystal Condie in a sweeping overview of a period of transition.

The well-known players are all portrayed, and with good humour. I’m inclined to think they are probably more intelligent than they’re shown in the changing room here, but the scenes of the beautiful game are beautifully choreographed, excitingly staged, and the penalty shoot-outs are edge-of-the-seat stuff.

Photos: Marc Brenner

At the interval, I was prepared to award 5 stars to this production. However, there was still a lot of story to tell, and Act 2 was overcrowded with incident, as is the recent history of the England team. Towards the end, it started to feel like a long evening, and that we’d gone into injury time. Nevertheless, it’s still a great play, brilliantly conceived and realised by both James Graham and Rupert Goold. By the time we reached Sweet Caroline, I was ready to join in. Good times never felt so good!

Our Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★

Group Appeal: ★ ★ ★ ★

Yes, it’s coming home! Most performances are Sold Out this season but it’s bound to be revived in time for the World Cup next year, and we’ll do a group visit.

<Joseph Fiennes / Gareth Southgate>

24/06/23 Jennifer writes –

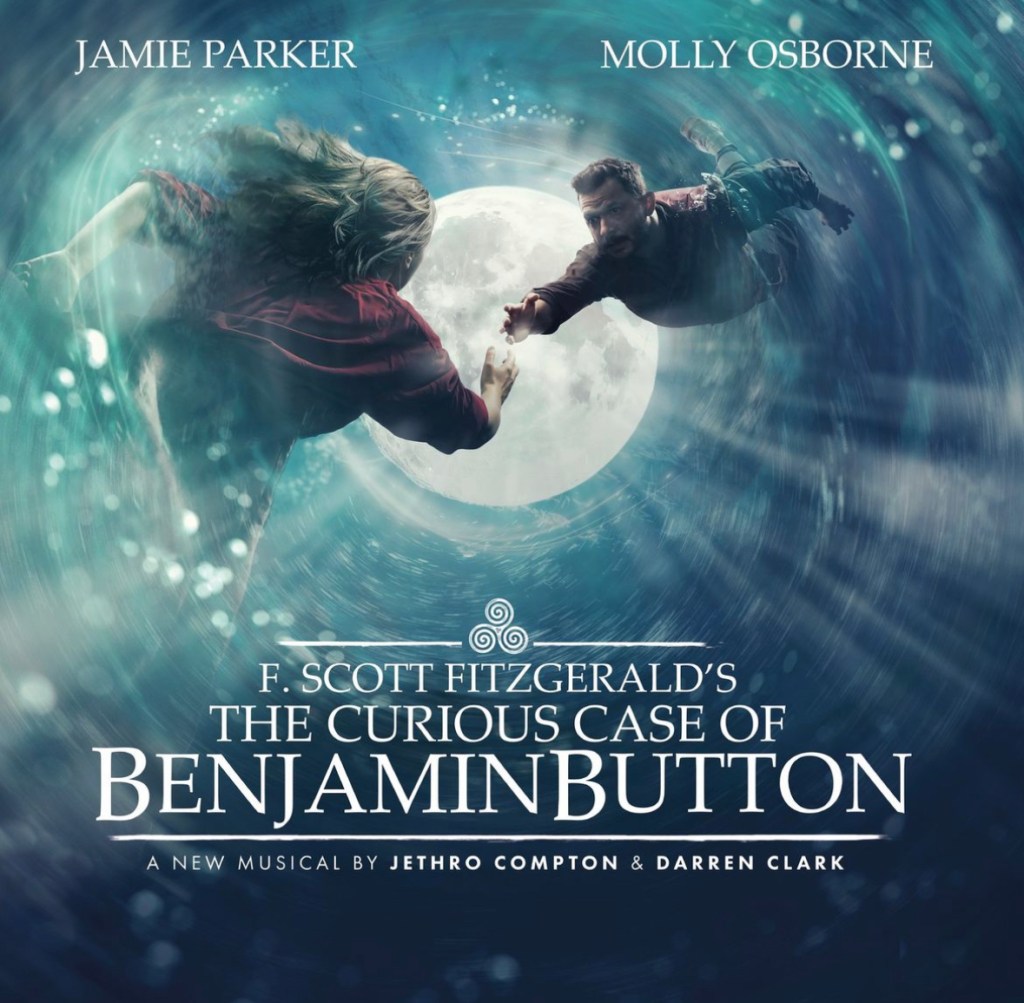

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Book & Lyrics by Jethro Compton, Music & Lyrics by Darren Clark, and movement direction by Chi-San Howard, at the Southwark Playhouse: Elephant

TCCoBB is based on a short story by F Scott Fitzgerald and was filmed to muted reviews some years ago with Brad Pitt as Benjamin, the man who’s born aged 70 and lives his life in reverse. In this re-imagined production, the action has been re-located to a seaside town in Cornwall in the 20th century by Jethro Compton, the Cornish born director. This folk musical version first appeared at Southwark Playhouse back in 2019 but is now revived and recast at the new venue Southwark Playhouse: Elephant.

Jamie Parker makes a welcome return to the stage as Benjamin after starring in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child in London and on Broadway. Jamie’s considerable charm, acting and singing skills are deployed to good effect throughout as he goes from playing the recently born old man to a gangly teenager, while singing and playing instruments in between. At this point, it’s probably a good idea to set aside logical and practical objections to this fantastical fable and allow yourself to be carried along for the ride. And what a ride it is.

Jamie is ably supported by a top notch cast of multi talented musicians and actors who also sing the Cornish folk tunes (better than you’d think!), play multiple instruments and characters while dancing jigs and reels and deftly moving a few props to create convincing scene changes.

As Benjamin takes faltering steps into the wider world, he experiences all the fates can throw at him: sadness, love, loss, prejudice, friendship and the hardship of war. We eventually see him happily settled with his wife and family although, as the clock ticks on, “time and tide wait for no man”, we know somehow (this is a Fitzgerald story after all) that this happiness cannot last, and yet more travails await….

The ending, when we’re told rather than shown, thankfully, that Benjamin is now a babe in arms, is bittersweet. I can’t have been the only audience member with something in my eye at this point. So, what is the moral of this modern day fable? Seize the day, remain optimistic, trust in fate and, when you find true love, hang on to it for all it’s worth.

Our rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ Group appeal: ★ ★ ★ ★

20/06/23 Mike writes –

The Pillowman

by Martin McDonagh, at the Duke of York’s Theatre (A preview)

Photos: Johan Persson

There’s something nasty happening at the Duke of York’s. Last time it happened was at the National in 2003 and, if I remember rightly, was much liked by the critics. “One of the greatest plays of the last 25 years.” Every Martin McDonagh play is both humorous and gruesome with underlying elements of human frailty and resolve – take his most recent lauded film, The Banshees of Innisheran, as an example. But remembering this play from way back, it startled with its black humour and violence, enough to be disliked by some. Fredo decided not to attend this revival, but I wanted to see how it fared twenty years on in a rather different social climate.

Katurian is a writer of children’s darkly comic fairy-tales, (more about than for them) played originally by David Tennant, but now gender swapped for Lily Allen to lead. She is being interrogated in a police state by two (funny) cops, one good (Steve Pemberton) and one very very bad (Paul Kaye). They are investigating several real murders of children which copy the deaths in her tales. She wants her legacy to endure even if she does not. It’s a whodunnit essentially – was it the writer or perhaps her retarded brother Michal (Matthew Tennyson)? Or is the playwright just telling tales within tales to lure us into a chamber of horrors?

There is violence (against a woman this time, because of the gender swap), extended verbal aggression, and the enactment of weird and jokey tales following a Grimm path. In one tale, a little girl who thinks she is Jesus is crucified by her parents, just to please her. Grim it is, with screams of offstage torture but, in much the same way that audiences loved the excessive pain of A Little Life, the abuse related here has an appeal which treads a careful line between shock and laughter. Beneath the surface we can look for explorations of fascism, fantasy and adult fears of feral children. And we can enjoy theatrical thrills along the way. For my preview matinée the theatre was full, and I did wonder whether in 2023 we have become too insensitive to nastiness. Or is it just the star casting that sells seats?

Lily Allen has a huge wordy role to play, a summit to climb but not yet reached, the words delivered but the effect muted, so let’s hope her efforts will give better rewards as the run progresses. Pemberton and Kaye are reliably on form but Matthew Tennyson hooks our attention best with a performance mixing innocent charm with pure evil.

I would have preferred a shorter visit to this nightmare world of contrasting tones and prolonged repetitive interrogation. Perhaps David Tennant (or even Colin Farrell) is the one who could get away with McDonagh’s excesses and make us grateful for visiting places we really don’t want to go. Is it still a play for our times? More so, if we go by the audience reaction.

My rating: ★★★ Group appeal: ★★

08/06/23 Mike writes –

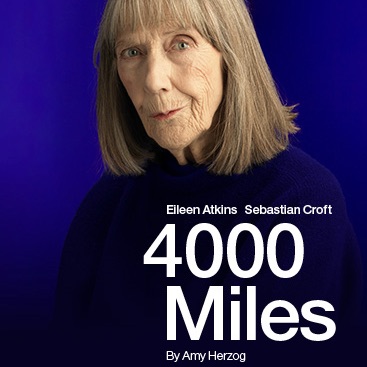

4000 Miles

by Amy Herzog, at the Chichester Festival Theatre

Leo has biked 4000 miles from California across country to visit his grandma in New York. He arrives with worries hiding behind his cheerful demeanour, keen to help out 90 year old Vera. Or is he really escaping into a safer space where she can help him?

We travelled not-so-far to Chichester to see Eileen Atkins in this play, cancelled at the Old Vic a couple of years ago by lockdown closures. The other big name, Timothée Chalamet has been replaced by Sebastian Croft who proves himself a good substitute to hold his own against Atkins who was on top irascible form. But was it worth both his and our journeys?

There are some plays which go down well Off Broadway, playing as comfort, for audiences demanding little except an ambiance they know and characters they recognise, no stretch, no worries to take home. A big name is an extra helping of familiarity. But such plays don’t always travel well to the UK, their comfort factors seeming of another place. From Chichester I doubt it will move on, though in NY with the right star it may attract an audience as here.

The big name is in place. We, and the senior Chichester matinee audience, were certainly not disappointed by Atkins who would be treasured as anyone’s granny – outspoken, cynical, caring and unquestioning. Leo and Vera spar amusingly, and scene by scene the reasons for that long bike ride come to the surface. But we wait in vane for some drama to bite, for some surprise to stir our emotion. The tone of the piece never reaches beyond bland, never further than a sketchy first-draft peppered with one-liners.

There’s an attractively furnished set, a lot of family gossip, phone-calls, two visitors…..and far too many blackouts for plumping cushions and showing time passing.

At the end Leo leaves, granny lives on. Do we care? Not a lot.

Our rating: ★★★

Group appeal: ★★★★

07/06/23 Fredo writes –

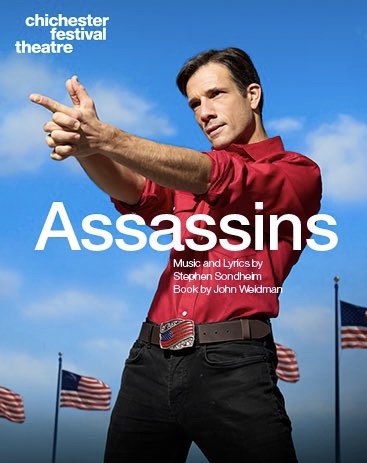

Assassins

Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, Book by John Weidman, at the Chichester Festival Theatre

Our rating: ★★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★★

It helps to be a Sondheim fan!

Assassins – they’re the other side of the American dream: the disenchanted, the dispossessed, the ones who feel they’ve missed their chances to enjoy life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. All they have to do is move their little finger to change the world. All they have to do is shoot to kill a President, become assassins, and find their permanent place in history.

It’s a difficult subject for a musical, tracing nine individuals across eight assassination attempts in a century (successful or otherwise) . It has to balance its tone between humour and horror; it has to tempt us to engage with its assassins then recoil from them. Yet Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman somehow find an appropriate idiom to present a vaudeville that places their stories together, blending song and script seamlessly, to construct a mosaic of their discontent.

Director Polly Findlay also finds an idiom for her spectacular production. We’re no longer in the usual fairground where the sinister Proprietor hands out guns to the assassins. It’s a political convention with bells and whistles, and cheerleaders encouraging a Mexican wave from the audience. And it’s a Presidential contender (Peter Forbes) who hands out the weapons to the prospective assassins seated among us. Any resemblance to a recent president is purely intentional ! The Proprietor is now a trio of storytellers, appropriately presenters from tv’s FXX News channel.

It’s usual to say that the show contains dark humour. In fact, some of the humour is simply hilarious, such as when Sarah-Jane Moore (Amy Booth-Steel) and ‘Squeaky’ Fromme (Carly Mercedes Dyer), would-be lover of Charles Manson, have a stand-off over Moore bringing her son and her dog to their attempted assassination of Gerald Ford (1975). However, the triumph of the show is the successful juxtaposition of these scenes with the more chilling moments, such as the electric-chair execution of Giuseppe Zangara (Luke Brady) who tried to kill Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933) but killed the mayor instead; and the killing of President John F. Kennedy (1963) by Lee Harvey Oswald (Samuel Thomas) shown in newsreel footage.

(Note: These scenes caused outrage in the local Chichester press. Phil Hewitt of the Sussex Express called the show “a horrid misjudgement from all concerned”, totally missing the point, and misjudging the show himself!).

There’s pressure on the cast to hit the right note (in every sense) and they work miracles in navigating the switchback changes of style and mood. Sondheim even composes his songs to reflect the style of music for each historical period. It’s a show where ‘everybody’s got the right to some sunshine’ of recognition, but they’re a uniformly excellent cast. Just to name two who hit the highest heights: Harry Hepple straddles the line between charming eccentricity and downright dementedness as Charles Guiteau – he had delusions of becoming ambassador to France but he shot President Garfield (1881) instead, and dances to the gallows; and Danny Mac reveals a saturnine side to his charming persona as John Wilkes Booth, a stage actor who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln (1865)- “Some say it was your voice had gone, Some say it was booze, They say you killed a country, John, because of bad reviews”.

John Hinckley (Jack Shaloo) wanted to impress Jodie Foster by shooting President Ronald Reagan, which he did, six times, without killing him. And then there was Samuel Byck (Nick Holder), a grubby Santa Claus figure dictating a tape to Leonard Bernstein. He wants to crash a plane into the White House and harangues the audience front row with his violent fantasy. It’s funny until it becomes disturbingly real.

I’ve seen this show in vastly different productions several times now, and there are two moments that have always brought tears to my eyes. The first is a brief dialogue scene between the activist Emma Goldman and Leon Czolgosz, the assassin of President William McKinley (1901), played by Sam Oladeinde. It’s short, and unadorned with flowery words, but John Weidman conveys the sense of social struggle underpinning the characters’ actions. The other scene is near the end, when all future and past assassins gang up to persuade Lee Harvey Oswald to join their infamous group. We’re almost on their side; their history of discontent is overwhelming – then the famous shot rings out from the Texas School Book Depository. Suddenly, the bystanders who have previously amused us with recounting How I Saved Roosevelt assemble with a heartbreaking rendition of Something Just Broke, demonstrating that Oswald has killed President Kennedy, but together the assassins have killed their American dream as well.

At the end, the assassins line up to confront the audience. In this production, they’re revealed in the Oval Office they have trashed – a vivid visual reminder of the attack on the Capitol Building by Trump supporters. They advance towards us, reminding us that everybody’s got the right to their dreams. They raise their guns for one last time. They’re aiming them at us.

It’s a work of genius reinvented in an inspired production. Congratulations to Chichester for presenting it on such an epic scale, and so brilliantly.

6/05/23 Kathie writes –

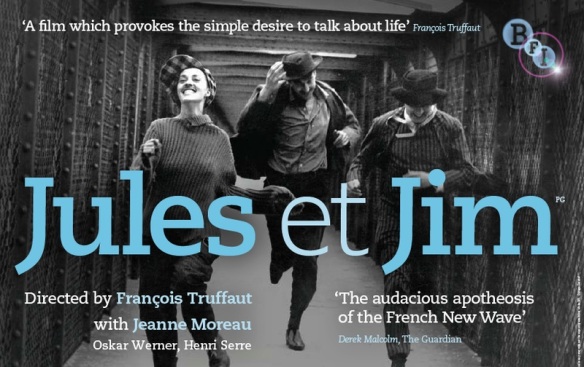

Jules and Jim

by Timberlake Wertenbaker, based on the autobiographical novel by Henri-Pierre Roché, at the Jermyn Street Theatre

I wasn’t familiar with the Truffaut 1962 film based on the book and in the 87-seat Jermyn Street Theatre this version was a more contained affair. Our cast of 3 presented themselves and their story using a mix of narrative to the audience interspersed with key scenes acted out. The set was sympathetically designed and used just a table and chairs, a couple of screens and a clever water feature.

We meet Jules (Austrian/writer) and Jim (French/translator) in Paris at the start of their friendship, pre-WW1, and a close and deep friendship is forged. In character they are quite different with Jim, extrovert and successful in attracting female company, the opposite of Jules, who is focussed on his writing, to the exclusion of anything else at times.

On a trip to Greece they come across a statue of a goddess. They are both entranced by her smile and imagine what it would be like to meet a woman with that smile.

Back in Paris they meet Kath (German) and, yes, she has ‘the smile’. Kath lives life by her rules, pushing and testing limits and boundaries with relish. She marries Jules, they move to Germany and war breaks out with Jules and Jim on opposite sides. When they meet, post-war, their reunion is poignant, both relieved that their wartime service in different arenas meant they couldn’t kill the other.

Kath now leads them both a merry dance, with other men mentioned at times, and we arrive at an almost inevitable conclusion.

This 90-minute distillation of their story was executed well and each actor was convincing in their roles. The element that didn’t work so well, and is so essential to the plot, was the belief in the chemistry between them that could generate so much passion.

Our rating: ★★★

Group appeal: ★★

Mike adds – Jules et Jim (the film)

I still have memories of Jules et Jim, the classic film dating from 1962 when François Truffaut (a founder of French Cinema’s La Nouvelle Vague) turned this bohemian novel into a quintessential milestone in French Cinema. It was so visual, so unstructured, so Truffaut and so French – I could not imagine it confined to any stage. But of course I had to see the play.

Coincidently, I found I had made notes on the film, almost 60 years ago to the day I was now seeing Jules and Jim again, this time in a theatre. Back then I called it “a film of great charm and fascination”; “the photography of sunlit woods, misty dawns, etc. is often very beautiful”; “the erratically edited film almost runs away with itself”; “Jeanne Moreau is at her most lively”. Ah, Jeanne Moreau, the doyenne of French Cinema, thought to be at her most luminescent in those avant-garde New Wave films.

As a comparison, after seeing the play, I decided to watch the film again on tv. In 1962 its setting during WW1 made it a period piece and now the film itself is a period piece very much of its time, a seldom seen treasure of those New Wave years. It’s still charming, but irritating too in its persistent bohemian quirkiness, it’s arty intellect out of step with today’s antibourgeois obsessions. It relies heavily on a voice-over commentary, perhaps taken directly from the novel, while the narrative is illustrated more than dramatised on screen. The characters jump moral and social barriers for their playful lifestyle, and today Kath at the centre of this ‘entitled’ trio would now be tagged with a patronising ‘syndrome’. I certainly remained “emotionally detached” from them, now as I did back then when first viewed. But it remains a joyfully indulgent fairy tale.

Jules et Jim, both novel and film, remain classics of their time, but now on stage as Jules and Jim and Kath they lose much of their charm and originality, and an earnest silliness takes over in a rather English way. It amuses, but why did Timberlake Wertenbaker bother when the classic originals still exist? I agree with Kathie’s rating and hope this new play may encourage some to seek out those originals. The book remains in print as well as the film (widescreen, monochrome) being available on Amazon Prime/BFI Home Cinema.

10/05/23 Fredo writes –

Dancing at Lughnasa

by Brian Friel, at the National: Olivier Theatre

Michael, the narrator now an adult, steps forward and sets the scene: it’s 1936, and he’s a child living with his mother and aunts outside Ballybeg in Co Donegal. My eyes filled with tears; no, it wasn’t nostalgia, it’s the carefully chosen words delivered with tenderness by Tom Vaughan-Lawlor at the opening of Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel.

Could this be Friel’s greatest play? It seems like a small domestic drama, even spread across the vast expanse of the Olivier stage, but as the story unfolds in Josie Rourke’s detailed production, the lives of the Mundy sisters reveal the personal tragedies in each of their lives.

It’s surely no accident that a writer so attuned to language as Friel chose the name “Mundy”. It makes us think of “mundane” and that is how they appear at first glance, as they carry out their domestic chores – ironing, knitting, baking bread, unpacking the shopping, worrying about their brother Father Jack, a priest who has been recalled from the missions. There’s a missing person: Gerry Evans, the father of Michael, Christina’s love-child. And there’s another character – the unreliable new radio, Marconi, which suddenly erupts with music (never news) at key points in the action.

With a masterly sleight of hand, Friel draws us into their world, where Catholic values co-exist with a suppressed form of paganism: rumours abound about rituals taking place in the back hills to celebrate the August festival of Lughnasa. Father Jack, who had gone native during his 25 years in a leper colony in Uganda, evokes the ceremony associated with the festivals in that country, and we see how close the civilisation of Ballybeg is to this primitivism.

This explodes in the play’s most famous scene, when Marconi comes to life with an exuberant Irish jig. The sisters can’t contain their suppressed emotions, and they release their feelings in individual ways. Extrovert Maggie stomps out her steps, demure Agnes trips through her dance lightly, Christina sacrilegiously pulls on her brother’s surplice and cavorts, and Rose skips childishly around. Even Kate, initially scandalised by this bacchanal, is eventually overcome, but leaves the cottage to dance privately her own variation of a traditional reel.

And then it’s over: unreliable Marconi cuts out, and the sisters are brought down to earth. For a moment, their euphoria makes them plan to attend the Lughnasa dance, but Kate puts a stop to that pipe-dream; women of their age would be a laughing-stock in that setting. Tensions rise to the surface when Agnes declares that Kate treats them all like unpaid servants.