Although this is the website for our theatre-going group, we sometimes go to the theatre by ourselves or with friends. This is the page where we intend to write about those theatre visits. The latest theatre visits are at the top of this page with earlier years on other pages (see below).

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2023

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2022

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2021

Click on this LINK for previous OurReviews2020

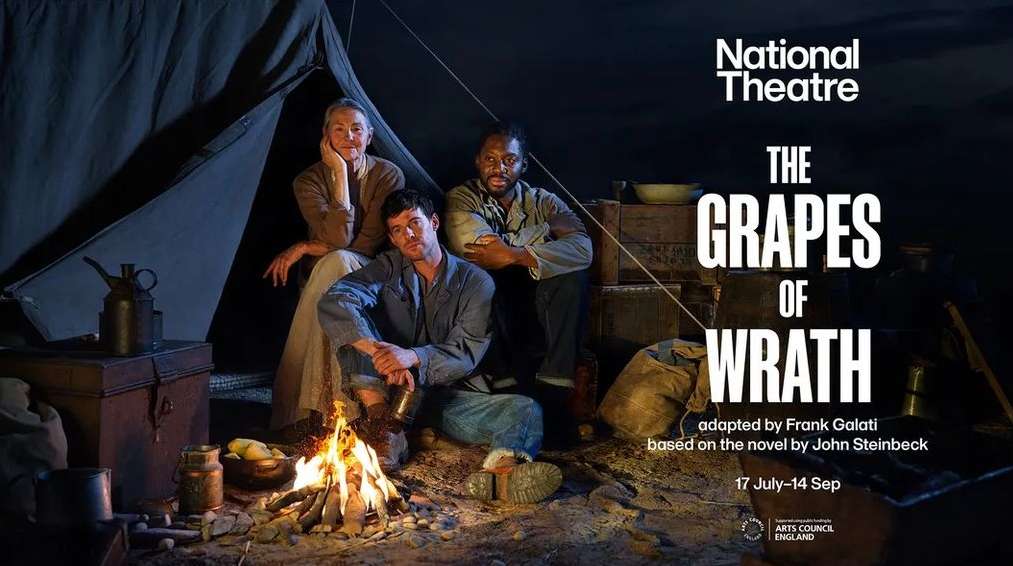

READ reviews with pictures for 2024, by the theatreguys and Group friends by clicking on the titles below (latest first): Ballet Shoes / The Importance of Being Earnest / The Tempest / Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake / Oedipus / Hamilton / Look Back in Anger / What we talk about when we talk about Anne Frank / The Devil Wears Prada / The Other Place/ Juno and the Paycock / The Fear of 13 / The Buddha of Suburbia /Dr. Strangelove/ The Duchess [of Malfi] / The Cabinet Minister /Giant / Turn of the Screw / Coriolanus / Hadestown / MJ / Billy Stritch / Giselle / Shifters / Here in America / Why Am I So Single?/ Hello Dolly! / The Real Thing / Hamilton / The Fifth Step / Our House/ The Years /When It Happens to You / A Chorus Line / Red Speedo / The Grapes of Wrath / Skeleton Crew / Mrs Doubtfire / The Voice of the Turtle / Boys from the Blackstuff / Slave Play / Mnemonic / Carlos Agosta’s Carmen / The Constituent / Alma Mater / Kiss Me Kate / A View From the Bridge / Phantom of the Opera / Jerry’s Girls / Between Riverside and Crazy / Bluets /The Cherry Orchard /Machinal / Operation Mincemeat / Sleeping Beauty / London Tide / The Comeuppance / Honestly, we’re fine! / The Ballad of Hattie and James/ Opening Night/ Harry Clarke / The Devine Mrs S / Player Kings / Two Strangers… / Long Day’s Journey Into Night / For Black Boys… / Abba Voyage / Faith Healer / Power of Sail / The Human Body / Duke Bluebeard’s Castle / The Merchant of Venice 1936 / Hir / Nachtland / Standing at the Sky’s Edge / Nye / Fanciulla del West / L’Oro del Diavolo / Just for One Day / Double Feature / Dear Octopus / The Little Big Things / Till the Stars Come Down / Stranger Things / Pacific Overtures / Rock’n’Roll / Matthew Bourne’s Edward Scissorhands / My Neighbour Totoro / Here We Are

18/12/24 Fredo writes –

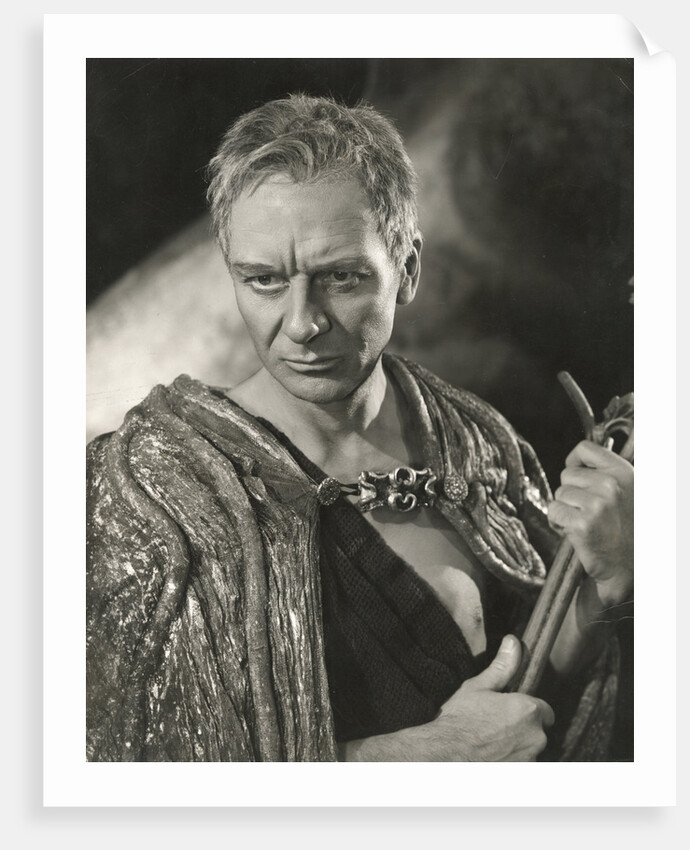

The Tempest

By William Shakespeare, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

Shakespeare’s last plays are regarded as masterly studies of redemption and reconciliation. Although I am an ardent admirer of his work, I can’t bring myself to approach these plays with any degree of enthusiasm. Cymbeline carries a great burden of tedium with an interminable last act, where characters are reunited and explain at great length to each other what the audience has endured for several hours. The Winter’s Tale interrupts a tense drama with an outbreak of shepherdess-itis in the fourth act. And then there’s The Tempest…

There are those – and I’m happy for them – who find layers of complexity in the tale of the exiled Prospero on his mysterious island enslaving the monstrous Caliban and the spirit Ariel, and seeking his revenge on his shipwrecked brother. It’s my loss, no doubt, that I feel queasy about the mixture of fantasy, magic and romance, the bending of tragedy and comedy and masque, and the higher than usual quota of low comedy. These are difficulties that any director of the play needs to overcome.

Unfortunately, I don’t feel that director Jamie Lloyd pulls it off. Despite his deserved reputation for inventive staging, Lloyd and his designer Soutra Gilmour present a dull staging of a play that needs all the visual help it can get. Yes, we have a flying Ariel (the extraordinarily gifted Mason Alexander Park), and flashes of lighting effects and billowing dry ice, but it all seems old-fashioned; I was expecting and hoping for a more radical interpretation.

There are pluses: it’s becoming a tradition for leading actresses to play Prospero. We’ve had Helen Mirren on film, and Harriet Walter at the Donmar. Now it’s Sigourney Weaver’s turn. Ms Weaver is a formidable presence, and is on stage throughout. watching the action. Strangely, this reduces Prospero to a passive observer, rather than emphasising her role as the agent of the play, whose decisions impact on all the other characters. This seemed to squander the actress’s command of the stage. The balance is slightly redressed in the second half, where Ms Weaver speaks Propero’s important speeches with clarity and authority. Selina Cadell, in another piece of cross-gender casting as Gonzalo, deserves a mention too (she always does).

I was grateful that they decided to cut the masque, but I wished they’d slashed the drunken comedy of Trinculo and Stephano (Mathew Horne and Jason Barnett), which does little to progress the action.

This is the first non-musical show at Drury Lane since 1957, when John Gielgud played Prospero, and was seen by a young Andrew Lloyd Webber, who decided to return Shakespeare to the Lane. This isn’t a theatre for an intimate show, and its size requires productions of epic dimensions.. Perhaps the next production, Much Ado About Nothing, will fit more comfortably.

About 30 years ago, Peter Hall ended his tenure at the National Theatre by directing all three of Shakespeare’s last plays. Mike and I dutifully went along to see them, and when we got to the end of the third one, Mike remained in his seat. He grasped my hand and said, “Please promise me that we won’t ever have to see The Tempest again.” I feel I’ve done my duty to this play now; in future, I’ll keep my promise.

Our Rating: ★★★/ Group Appeal: ★★★

17/12/24 Mike writes –

Not one but two Christmas treats from the National Theatre this year. We were expecting and wishing for the return of Roald Dahl’s The Witches from last year. Instead, maybe next year, and in the meantime we have no complaints about this year’s choices.

The NT has gone all out for entertaining the whole family and we managed to see both The Importance of Being Earnest and Ballet Shoes around one weekend – certainly two treats full of Joy for the Festive Season.

The first was Earnest (reviewed below) and seen OnOurOwn, then a small group enjoyed Ballet Shoes with us, our final Group theatre visit of 2024. But why so small, why so few bookings? Is the title now unknown or forgotten. It was once on every child’s book shelf, beloved by parents and children, and surely ready for a stage adaptation. The NT has given it a premium treatment, and I loved it with a grin on my face throughout. It had great entertainment appeal for both the young and the not-so-young but young-at-heart, with extra aspirational suggestions for the kids and a nostalgic wallow for us oldies. The dance numbers were a theatrical fun-fest and the plot kept us hanging on to every turn. Those not with us missed a theatre treat. The Group’s opinions will appear on the Your Comments page.

The Importance of Being Earnest

By Oscar Wilde, at the National: Lyttelton Theatre

Oscar would have approved. He delighted in showing off the manners of High Society, the heritage obsessions and class snobbishness of his day. A baroque torrent of witticisms is displayed in a tangled romantic plot to be unravelled only at the final curtain. It is all most definitely ‘of his day’, very far from today. His writing could be over-familiar with today’s older audiences but probably unknown to the new generation of theatregoers. How to revive it, and even why?

Director Max Webster thought “Footlights, camp, attitude!” and has taken the decision to spend money, cast well, pep it up to farce level, then let the words, with suggestive intonation, carry it along at a spritely pace. Surprisingly, it works, for young and old alike judging from the audience response. And I’m with them.

Intimate pals Algernon and Jack are psyching themselves up to marry while giving no indication they are the marrying kind. The first hurdle is Algernon’s snobbish gorgon aunt, Lady Bracknell – her every decision is beyond discussion, especially regarding her daughter Gwendolen whom Jack intends to marry. But Gwendolen insists on marrying an Ernest, any Ernest, but certainly not Jack. Algernon has made up his mind to marry Cecily who is Jack’s ward. However, Lady Bracknell disapproves of Jack’s unknown parentage and therefore of her nephew’s marriage to Cecily. This sets Algernon and Jack at odds with each other. The resolution to both the thwarted affairs will only be found with the discovery of a famously missing handbag. Yes, “A handbag!”, possibly the most famous line in all of Wilde’s work. Oscar is on form.

Top-of-the-bill colour-blind casting proves a bonus. Ncuti Gatwa (he of the knowing smile and our current Doctor Who) is the perfect embodiment of Wilde’s exuberant and scheming Algernon, here allowed to cross-dress and display a wardrobe of floral prints worthy of Sanderson’s best wallpapers. His foil, the panicked but determined Jack, is played by Hugh Skinner with a flamboyance well above his usual retiring nature. Sharon D Clarke at her haughtiest (back of steel, sneer at the ready) is a joy as Lady Bracknell with costumes to dazzle the rear Circle. I must also mention Ranke Adékoluéjó as a demure yet skittish Gwendolen who steals scenes with her looks of knowing glee. Add to the mix a prissy Miss Prism (Amanda Laurence) and a fey but doting Reverend Canon Chasuble (Richard Cant) and you have a simmering sexual soup of frustrated high class couplings.

This elegantly produced three Act play is here given one central interval which cuts the original second Act in half – an odd choice as the Interval comes abruptly, devoid of any flourish. But Part Two picks up the pace again and any slight misgivings at the Interval were swept away. Another plushly theatrical set and some divinely played comedy lets this stylish romp rise to its inevitable climax. And then….more costume changes for a bespangled roof-raising curtain-call which in a musical would have been a mega-mix cuing the ovation. It’s fabulous fun, dressed to impress, and it does.

Our Rating: ★★★★½/ Group Appeal: ★★★★

20/12/24 Jennifer adds –

A quick note to say I enjoyed your review of The Importance of being Earnest although my own view was that the production was like an over iced fairy cake (pun intended); delicious at first but made one feel over indulged and longing for a more subtle approach as time went on. Maybe Max Webster got a bit carried away with the resources available to him at the National? It’ll be interesting to see what he does next.

Photos: Marc Brenner

06/12/24 Fredo writes –

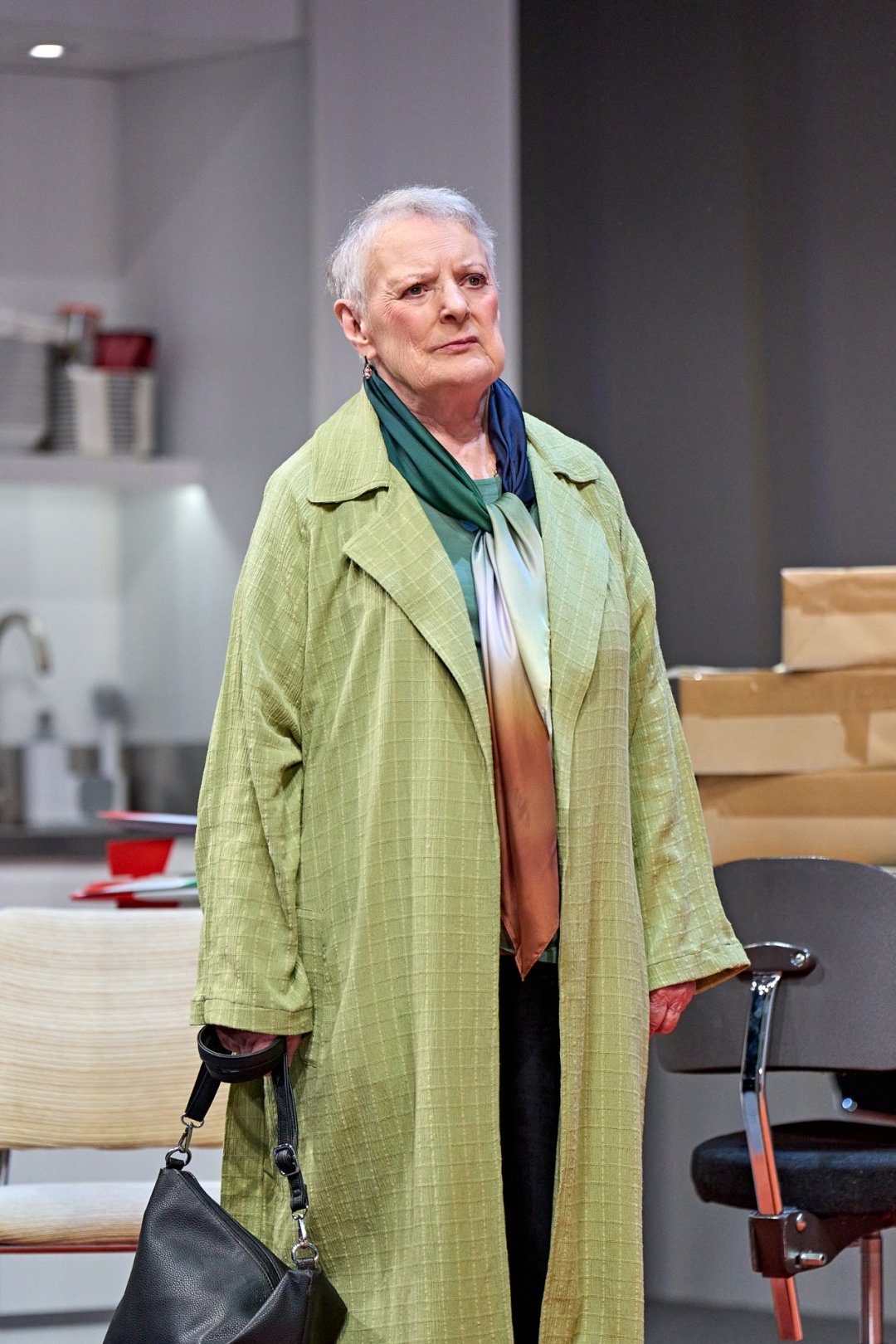

Oedipus

Written and directed by Robert Icke, after Sophocles, at Wyndham’s Theatre

There’s a problem: Oedipus, the leading candidate for Premiership, has a fetish for honesty. He’s promised that if he’s elected, he will publish his birth certificate to silence rumours about his nationality, and he’ll have an investigation into the death of his wife’s first husband Lyas 24 years ago. But things aren’t going to be that straightforward.

In the cluttered campaign headquarters, his mother Merope insists on a private meeting, and his wife Jocasta and her brother Creon aren’t keen on going over the murky details of Lyas’s death. However, the three children still provide a distraction with a surprise celebration dinner for mum and dad, but this descends into a family argument between Antigone and her mother Jocasta. Antigone storms off, with the parting shot, “It’s always about fucking mother.”

Of course it is. The play is Oedipus, and Robert Icke has taken Sophocles’s tragedy and remade it for our own time. I worried if the ancient story would stand up: a foundling returns to his native land, accidentally kills his father and marries his mother, which might provoke mirth rather than horror on the modern stage.

However, Icke has adapted the story with plausible contemporary equivalents (a political manifesto, a child abused, a fatal car crash…) and his script achieves both narrative clarity and poetic expression. As the stage is emptied of its furniture for the public announcement of an election result, revelations tumble out, each one carefully introduced to arrive with maximum impact. The drama becomes more horrifying, more powerful and tragic than ever before.

Icke is blessed with a flawless ensemble cast. The always-reliable Michael Gould is a nervy Creon, possibly jockeying for power, as Oedipus suspects – or is he just anxious not to reveal the truth about Lyas’s death? June Watson is more implacable than ever as a disapproving grandmother of Antigone and her brothers. Her revelation that she is not the mother Oedipus thought she was is a heart-stopping moment.

The play rests on the performances of Oedipus and Jocasta, and here Icke is holding two aces. Both Mark Strong and Lesley Manville have the gift of naturalism on stage, and the ability to segue from this to the histrionic heights without effort. Their scenes together are a masterclass, as the affection and security of their love drains away with the realisation of what they are involved in. These could well be the performances of the year.

There’s been a revival of interest in Greek drama. We recently had Sophie Okenedo and Ben Daniels in Medea, and there’s a production of Sophocles’s original play coming on at the Old Vic. Writers like Pat Barker and Natalie Haynes have been providing new perspectives on these ancient myths in their novels. This is where all the great tragic archetypes were conceived, and we seem to have a need to return to them and examine them afresh.

Robert Icke’s contribution is in the first rank in this peerless production.

Our Rating: ★★★★★ / Group Appeal: ★★★★

What was I thinking of? Mark Strong and Lesley Manville together! Why didn’t I arrange a group visit? In truth, I was worried that Robert Icke’s production might be a bit tricksy (he’s had form in the past). Also, Matthew Warchus is directing the original play at the Old Vic in the New Year, and I was torn. In the end, I didn’t book the Group for either. Now I have to find a corner where I can beat myself up.

Mike adds: Not just the performances of the year but maybe The Play of the Year too. And there’s stiff competition from at least two other contenders. Is this a New Play or a Revival, one may wonder. For me it’s all new – forget the ancient tragedy, this is convincingly of Today. I can just see June Watson as mother of Starmer or Davies. And Badenoch who, in her daughter’s eyes, would be seen as another fucking mother! In addition, the narrative is so well transposed to today’s political arena, that I totally forgot I knew the climax, and literally dropped my jaw when…no, I won’t say, as thankfully some audience members will not know the outcome. It comes as realistically, devastatingly, and inevitably as it must have done in ancient times. The audience were stunned – pure, great Theatre for the 21st century.

Photos: Manuel Harlan

20/11/24 Garth writes –

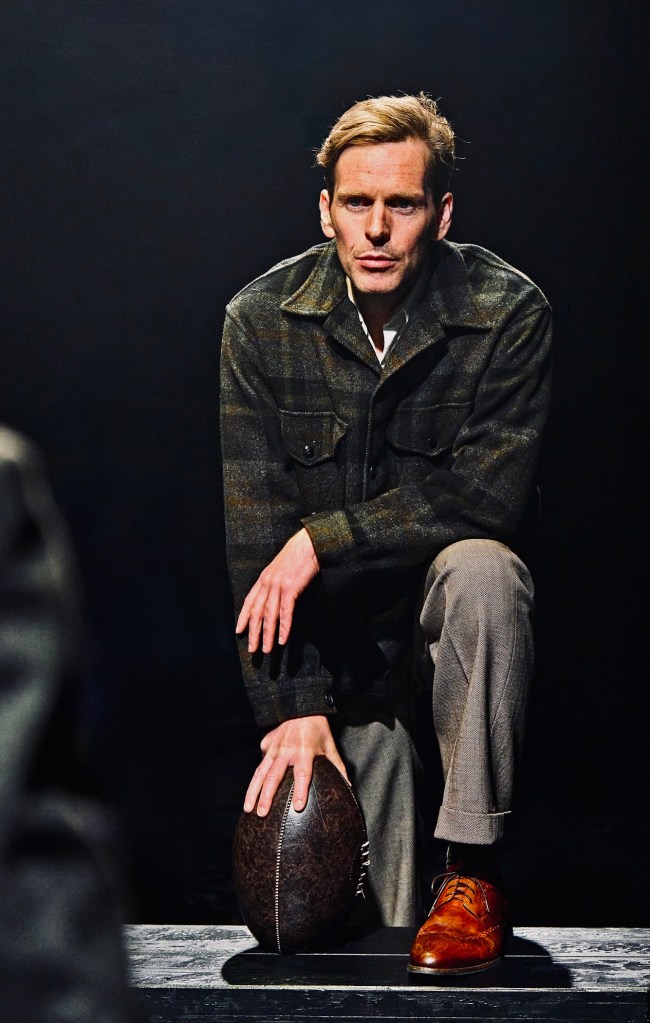

Look Back in Anger

By John Osborne, at the Almeida Theatre

The play comes with some heavy baggage in the history of British theatre – kitchensinkery, angryyoungmannery, RoyalCourtery, notoriety, and so on – and the decision to stage it in London for the first time in 25 years was a good one. If Look Back in Anger was (or proved to be) perfectly and daringly in position when it opened in 1956, how does it stand in 2024?

Not having seen the play before, I flatter myself that my appraisal is objective and devoid of comparisons with past productions. How does it stand up as a play, as distinct from as an icon?

As the metaphorical curtain rises, we are met by a red-lit circular revolve – is it a circus ring? – with a useful core that occasionally rises and falls bearing a chair or two or a table or the famous ironing board or even a person: there’s little to prompt us to imagine that this is a scruffy flat in a dull provincial town in the 1950s. In due course we pick up these points, but I guess that the director Atri Banerjee was aiming to purge the piece of some of the accidents of time and place to reveal the quasi-timelessness (or modernity) that lies at its heart.

The play is about relationships, some triangular, all of which arouse our curiosity – Jimmy Porter (Billy Howle) and his put-upon wife Alison (Ellora Torchia) endlessly tied to the ironing board, and Cliff (Iwan Davies), the amiable lodger, with whom Jimmy works in a job that is really beneath his university-educated dignity. It’s Cliff who displays a measure of tender physical affection for Alison, in contrast to Jimmy’s virulent “coercive control” of his wife. Cliff and Jimmy more than once engage in laddish banter and wrestling bouts. Whatever overtones such activities may hold – surely a man who smokes a pipe (!) can only be all man – the fraught marriage appears to require a sub-Freudian “Bear and Squirrel” game in order to overcome its hang ups.

Jimmy’s relentless verbal assaults on everything and everyone around him – the playwright seemingly called them arias – are painful to hear, more intense than bar-room rants but of course equally repetitive and depressing. Here lies the anger, the sense of failure, the prickly class-consciousness and resentment of Alison and her establishment parents and their hostility to him. These feelings, even though sometimes springing out of nowhere, can be acknowledged against a world (in 1956) of Cold War politics, the Soviet invasion of Hungary, the Franco-British invasion of Suez and plenty more horrors and (today) against a world that is wracked by new versions of cruelty, hopelessness and uncertainty.

Alison’s surprise pregnancy drives the second half of the play. (I wondered briefly whether Cliff rather than Jimmy might be the father). Ostensibly Jimmy is unmoved by the news when eventually Alison’s friend Helena (she of the Penelope Keith accent) (Morfydd Clark) breaks it to him. Having persuaded the care-worn Alison to return to her parents, Helena stays on in the flat, seamlessly taking Alison’s place in Jimmy’s bed – and possibly in his affections too.

With Helena installed at the ironing board, relationships seem a tad more benign but inevitably, instability intrudes: Cliff decides to move elsewhere and, dauntingly, a desperately wretched Alison, having suffered a miscarriage, appears at the door. This in turn prompts Helena to examine her conscience and to decide that “living in sin” had been wrong. With her departure, as dark ashes fall from above and the play comes to its end, Jimmy and Alison cling together – in despair, mutual comfort, love…..

I was impressed by all the performers in their roles (Ellora Torchia especially expressive), by the polished nature of the production and by its timeliness (and even “relevance.”) It’s not just in the pages of The Guardian that “toxic masculinity” and associated modern tropes raise their heads. Jimmy’s ugly effusions are surely expressions of deep insecurity and self-doubt in a changing society, of an ongoing inability to manage his life, of inherent weakness, of fear that he is the squirrel, not the bear. He wants things to change – and yet not to change….he doesn’t smoke that pipe for nothing. You could argue that he’s such an unbearable (sorry) character, it’s a wonder that women fall for him. Bernard Shaw once grouped his output into Plays Pleasant and Plays Unpleasant. I haven’t had the chance to explore the criteria, but LBIA must surely be an unpleasant play, open to the accusation that Osborne assumes that it’s the man’s problems alone that warrant exploration. As a drama, its construction is pretty basic – Cliff and Helena (not to mention Alison’s father) are mere devices to move the action on – they drift off the stage into total oblivion and no one cares about them.

Alison of course attracts a strong and direct sympathy from the start, but at the ending, I did at last care about not just her but the pathetic Jimmy too, begrimed in ash and locked into a union of last resort. It was at that moment that I thought: whatever else it’s about, LBIA is about love or rather more precisely, it’s an illustration of W H Auden’s line: “O Tell me the Truth about Love.”

Our rating: ★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★

16/11/24 Mike writes –

What we talk about when we talk about Anne Frank

By Nathan Englander, based on his short story, at the Marylebone Theatre

It’s the one everyone is talking about, should be talking about, and is possibly the most highly rated play of recent months. And it’s Off West End at a small theatre near Regents Park. It’s 100% kosher, written, directed, and acted….but not, I hope, only seen by Jewish audiences. It’s for us all, especially today, when it picks up today’s big topic, plays with it, jokes with it, but always treats it with balanced consideration and respect.

Caroline Catz / Joshua Malina / Simon Yadoo / Dorothea Myer-Bennet + Gabriel Howell.

Photos: Tristram Kenton

Two American couples get together to rekindle the school-days friendship between the two wives. Debbie and Phil with their son are secular Jews but Lauren and Mark, their returning visitors from Israel, are now ultra-Orthadox and renamed Shoshana and Yerucham. The play, based on a 2011 short story, has been updated to ’now’ with the Israeli war in everyone’s mind and opinions all across the spectrum.

Jewish life, history, traditions, problems, relationships, and humour, are tossed around adroitly and irreverently as the two couples encircle each other in friendship and combat, adjudicated by Debbie and Phil’s teenage son on the sideline. It’s a fair play, pacily directed by Patrick Marber.

Tollerance and understanding only last until the first toast. Each character is a type we recognise with their own responses to coping in a difficult social circumstance. They each want to be friendly yet find themselves outside of their comfort zones, alternating between laughter and tetchy embarrasment with flashes of anger. That may be the audience reaction too! The son introduces each scene to us, comments inappropriately at the adults’ sparring, and stirs the melee for our maximum amusement. As the wine bottles empty, opinions are targeted, shot-down with humour, then mended by retreat.

The visiting couple have seven daughters; what happened to the eighth is a turningpoint in the play. Eventually the talk has to come around to Anne Frank, in a truth game which both hurts and heals. As in war and as in life, there has to be compromise. This comes at the emotional end of this powerful comedy and is sure to leave everyone talking. It must, please, transfer to a larger theatre for a larger audience to enjoy. It’s a small gem of a play with a big subject and a big heart.

Our rating: ★★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

13/11/24 Garth writes –

The Elixir of Love

The opera by Donizetti, the Englist National Opera company at the London Coliseum. A Dress Rehearsal.

As so often, Dame Fortune’s unpredictability has prevailed and, on this occasion, “OOO” turns out to be neither Fredo nor Mike but yours truly with two companions wedged into the front row of the Dress Circle. This position afforded a close view of the stage and the pit but little room for the legs.

Any concern about potential DVT was soon swept away by this very pleasing production (director Harry Fehr) of one of Donizetti’s most popular works, dating from 1832. Back then it was described as a “melodramma giocoso” and from the off was a great success, plucking heartstrings and tickling funny bones. The touching aria that begins “Una furtiva lagrima” as rendered by Caruso in 1900 cemented his fame.

At ENO, we are not in early 19th century Italy but in the dreamy days of World War 2 in sunny rural England, a stately home still staggering on as young Adina gets her tenants to dig for victory. It’s a sort of Betjamesque idyll, all hearty landgirls and fairisle pullovers. Add in a whizzoprang RAF WingCo (Belcore) seemingly on the point of frustrating the hopes of the timorous Nemorino of landing Adina as his bride. But out of the blue along comes Dr Dulcamara and his bottles of dodgy cure-alls – aches and pains will disappear and that goes for bad luck in love too. Nemorino pays a high price for his (alcoholic) elixir but in the end (somewhat indirectly) it enables him to get the girl!

Assessing any show at dress rehearsal stage is likely to be at best treading on thin ice. Here, the audience was advised that the production was still work in progress and that singers could be protecting their voices by perhaps not “singing out.” On top of this, Thomas Atkins (Nemorino) was not singing at all but doing a walk-through – happily his understudy, Joseph Doody, singing from the side of the stage, was an admirable and affecting substitute.

And indeed, the tone of sentimental comedy was well judged on all fronts. Amanda Holden’s wittily rhyming English version of the libretto went down very well. Donizetti’s beguiling bel canto melodies were beautifully handled both vocally and orchestrally. In the pit, Teresa Riveiro-Böhm managed the orchestra sympathetically, never swamping the singers. As Adina, Rhian Lois proved to have a strong silvery voice that scaled the heights impressively and was more than capable of keeping her suitors on their toes. Belcore (Dan d’Souza) was a convincing self-regarding blusterer (always closely guarded by two surprisingly athletic airmen). As Dulcamara, Brandon Cedel exuded baritonal smarm and guile (of course, in the spirit of things, he was in no way threatening – though I’ve always been told never to trust a man who chooses to wear a brown suit). The lively chorus had plenty to do and did it well.

It’s worth noting that this production featured (as far as I could tell) youngish performers, though judging from the principals’ biographies, they already have wide professional experience in this country and elsewhere. I wonder if the Arts Council has noticed that ENO’s encouragement of young talent has always been a key part of its rich history.

As a footnote, I can confirm that the warmly appreciative audience did not engage in fisticuffs or singing along or other forms of unseemly conduct (see references elsewhere on the FTG website on trends in audience behaviour). It was however rather sad to see that not all of the Friends of ENO (for whom the dress rehearsal was open) could be bothered to take away with them their used glasses, paper cups, crisp bags and other detritus……

03/11/24 Jennifer writes –

The Other Place

A new play by Alexander Zeldin, after Antigone, at the National: Lyttelton Theatre

The play is intriguingly titled ‘after Antigone’, so we were interested to see how the playwright would adapt Sophocles’ Greek tragedy. It’s about the daughter of Oedipus (yes, that Oedipus) and Antigone’s battle of wills with King Creon of Thebes, over her brother’s burial with full funeral rites following his death in battle. Antigone is considered a tragic hero for supporting her family (as required by the gods) over her loyalty to the state (embodied by Creon).

Photos: Sarah Lee

The play opens in a well-appointed modern, domestic kitchen in the midst of building work to include large picture windows and a kitchen island. The blended family within (each of whom has a name starting with the same initial as their Greek counterpart) is headed by Chris with his wife Erica, her son Leni, and Chris’s niece Issy. His other niece Annie is returning after time away for a ceremony to scatter the ashes of Chris’s brother, the nieces’ father. Terry, both a family friend and the building work project manager, becomes involved in the family dynamics for reasons that are not immediately apparent.

Initially, the bourgeois pretensions of the family are neatly skewered, drawing laughs (perhaps of recognition) from the audience. However, once Annie arrives, her grief and resistance to scattering the ashes darkens the mood. Annie and Chris engage in a battle of wills, various secrets are revealed, and family tensions explored. However, despite the best efforts of the cast (Tobias Menzies and Emma D’Arcy are particularly good as Chris and Annie) the story unfolds without appearing to make any sense. Inevitably we are led to a would-be shocking but not entirely unexpected denouement (no spoilers here). The Greek playwrights could invoke the gods if they needed to move a plot along or explain away a contradiction in the narrative. Sadly, Mr Zeldin did not have recourse to divine intervention in his modern re-telling and credibility suffers as a result.

Incidentally, I thought the thanks in the cast list for the contribution of Michael Morris for ‘Sibling Research, Recruitment and Participation’, and Julia Samuel, the well known family therapist who has worked with our royal family, told us quite a lot about the production. Maybe the NT needs to think more carefully about whether the Greek tragedies, so rooted in a particular time, place and moral code, can be updated in a way that’s relevant and engaging for modern audiences.

Our rating: ★★½ / Group appeal: ★★

30/10/24 Garth writes –

Juno and the Paycock

By Sean O’Casey, at the Gielgud Theatre

Mike says – We had side seats in the Gods paying a mere £20 for this one, not the usual treat that FTG offers. Did it affect our response? Garth has sent in his thoughts, but first maybe I should explain that this ‘old fashioned’ production, complete with dusty red velvet curtains and brassy footlights, began as broad Father Ted comedy (Mark Rylance has a Chaplin/Hitler moustache) finishing eventually as mawkish tragedy – gunshots, an unexpected death, the stage empty, floorboards being pulled up, with a huge Pieta statue overlooking it all. A small crucifix glistened above the stage throughout. Director Matthew Warchus was most evidently insisting he was in charge!

Little wonder that our comprehension of some of the words was difficult – if you look at the play text (which is titled “a tragedy in three acts”), you find it’s written in dialect or even Oirish…. “dhrink of wather” etc….. Is one to take this as a condescending device to demonstrate that the folk depicted are from the lower orders who would never darken the doorstep of the Abbey Theatre? Interesting also, the stage directions are very Shavian, complete with precise descriptions of each character and stage business.

The production seems to have stuck quite faithfully to the text, though maybe purged of lots of religious oaths etc. The final scene as written is still in the Boyle’s house, stripped of all furniture, but not here; the jazzing up with pistol shots and the death is not in the text. But O’Casey is mischievous even at the last moment when he has the Captain bemoan the fact that “the whole world’s in a terrible state of chassis”.

The playing last night was pretty broad but clearly O’Casey’s trajectory is from the chirpy opening episodes through to the grim conclusion. At the start, the Rising, the Civil War and associated terrorism are a background, with Johnny a living if peripheral victim of those events, but by the final act they have come right into the house with destructive force, and the sorry stories of the inheritance and the shaming pregnancy effectively run in parallel.

O’Casey’s trio of plays (this one [1924], the other two being The Shadow of a Gunman [1923] and The Plough and the Stars [1926]) were I guess still pretty topical when first produced, even though the Rising was back in 1916. Were they the equivalent of gritty telly dramas – Play for Today etc?

I enjoyed the show and particularly relished the energy and enthusiasm of the cast. I didn’t feel that Rylance stole the show at the expense of other characters that some reviews complained of. He was of course charismatic but his character is the lynchpin of the drama, after all. I thought Joxer (Paul Hilton) was very well done. Juno (J. Smith-Cameron) perhaps didn’t make much impact but she might have done if I’d understood better what she said. Likewise, the singing lady (Anna Healy) was terrific, tho incomprehensible.

Very glad to have seen it, knee-room limitations permitting.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

27/10/24 Mike writes –

The Buddha of Suburbia

Based on the book by Hanif Kureishi, adapted for the stage by Emma Rice with Hanif Kureishi, transferred to the Barbican Theatre from the RSC’s Swan Theatre in Stratford.

It’s 1979 in the London Borough of Bromley, and Karim is celebrating no longer being a teenager. He is the son of a British mother and Indian father, is “British through and through” but has all the ‘fitting in’ problems those of his racial mix had at that time. He loves his family and friends but wants to escape the varied traditions which are trying to influence his life.

But let’s not worry too much as Karim is having a great time, thanks to Hanif Kureishi’s now-classic and possibly biographical 1990 novel. It was a tv series a while back but now Emma Rice has brought it to the stage in her energising theatrical signature-style which suits the narrative perfectly. Its humour, colour, vitality, and emotions are shared with us all.

At the start, Dee Ahluwalia as Karim introduces himself to us directly, and immediately we hang on to his narrative like it’s the most addictive of soaps. We feel for him as he tells his story and reacts to the ups and downs of a turbulent lifestyle – his confused sexual orientation, his father’s affair, the break-up of his parents marriage and his divided life between two families, two traditions, plus sex, songs, sadness and joy with a multifarious group of friends. And then comes his introduction to a hip theatre director and a changed life on the stage.

The sheer verve of the production, the humour, the suburban Indian setting, the generational differences, all are a joy to experience. Who could guess that life in Bromley (with bonking, balloons, glitter and an animated fox) could be such fun, at least from the Stalls.

Dee Ahluwalia is a great compere to these kaleidoscopic events and the rest of the cast tackle multiple roles with enthusiasm. I particularly want to mention Ankur Bahl as Haroon the Father (etc) adept at yoga poses and self promotion, and Rina Fatania as a flirty but adoring Auntie Jean (etc), both bringing an individual humour and delight to their quirky characters.

Director Emma Rice is back on form here, just as she was years ago with her very own-style stage adaptation of Brief Encounter, and she guarantees we all leave the theatre with a smile…and a better degree of understanding for Karim and his community.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

24/10/24 Mike writes –

Dr. Strangelove

Co-adapted by Armando Iannucci, directed and co-adapted by Sean Foley, from the Stanley Kubrick film. A preview at the Noel Coward Theatre

Even if you haven’t seen it, most people of my age know of the Stanley Kubrick movie “Dr Strangelove, or how I learned to stop worrying and love the bomb”. For this adaptation Armando Iannucci, with Sean Foley directing, has ditched the longer title, given Steve Coogan four roles instead of Peter Sellers’ original three, and remembers that many world leaders still love the bomb. We are all at risk from the current leaders Putin and Netanyahu with their continuing warmongering so now is a timely moment to stage the film.

However, this is basically just a two-set sitcom (plus a cockpit with back projection), no advance on Iannucci’s tv work, nor state-of-the-art stagecraft which it could have been. Most of it takes place around a US war-room table (“This is a war-room. We want no fighting here!”). The jokes come along rata-tat-tat and the audience substitute for a tv laughter track, recognising when to laugh. But none of it is really as funny as I wanted, nor the biting satire that I hoped for. The opening chorus line of singing and dancing military personnel is a good stage joke, but is never repeated until the very end. Coogan’s costume-changing is smoothly achieved but not with the aplomb of say Mrs Doubtfire changing gender. But sometimes he does seem to appear as two characters on stage together.

Coogan does his best with the script given him, three roles played as straight comedy with only Dr Strangelove himself (manic in a wheelchair but not a big role) bringing the comedy excesses expected. The all male cast work hard for us, especially Giles Terera and John Hopkins as two stressed Generals, but the final appearance of a woman brings a surprising and welcome change of tone, a touch of nostalgia, which emphasises this is nothing new at all but a comforting stagey interpretation of the iconic film.

I saw a preview from my partially restricted view in the third tier Gallery (£29.50). Seats in the Stalls range from £209.70 to £65 in the back row, but the names of Kubrick and Coogan are selling the tickets. A man sitting next to me (no, Fredo declined to join me) said he enjoyed it. I did too, but not as much as I expected with this A team involved. It’s not an update for the 21st century, no advance on Kubrick.

Our rating: ★★★ Group appeal: ★★★

Photos: Manuel Harlan

22/10/24 Fredo writes –

The Duchess [of Malfi]

Written and directed by Zinnie Harris, at the Trafalgar Theatre

I don’t blame the actors – though they must have read the script. It’s by Zinnie Harris, who also directs, and she has adapted it fairly freely from the Jacobean revenge tragedy, The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster.

There was a time when I had to study this period of English Literature, and I tried very hard to convince myself that I was impressed by this genre. Granted, all the dramatists show up as poor seconds compared to their near-contemporary, William Shakespeare; they haven’t got the flair for plotting, character-building, language and poetry that flowed effortlessly from Shakespeare’s hand. Webster was probably the best of them, as he imbued his sensational tragedies with some sense of drama and import.

Take away his language and the period settings, and what you’re left with is a fairly unconvincing story with a built in “So what?” factor. The original, dating from 1613, gives us a woman crushed by her position in society, who despite her wealth, is a victim of the patriarchal family environment. None of this survives the transition to a bland contemporary setting. Stripped of Webster’s ornate poetry, the play sounds like one of those parallel texts, now with conversational crudities, designed to make Shakespeare accessible to present-day students.

Even so, I was willing to go along with the first act (Mike was less forgiving). It was good to see Jodie Whittaker on stage again, and the actors in the minor roles acquitted themselves well. Unfortunately, none of the four leading men were given any sex appeal whatsoever, instead they paraded an aggressive and exaggerated foolishness, apart from the wet commoner the Duchess married. In this play, a lot depends on believing that there is an insurmountable sexual attraction between the leading characters of which there was none (yes, there are overtones of incest thrown into the mix). By contrast, the women are pragmatic and relatable, but victims nevertheless.

A small bonus was a song, by Jodie Whittaker in slinky red dress, sung at the start in cabaret style, before her persecution began. Less welcome was a young woman, in white trousered garb with guitar, who occasionally wandered into proceedings strumming, to add a feminist vibe.

After the interval, it was downhill all the way. The actors were required to do things that were ludicrous and incomprehensible. The actors who valiantly parroted the excruciating dialogue were now called upon to demean themselves in humiliating actions. I’d been chatting to the man in the next seat, a visiting American, and I was embarrassed that he might assume that this was the standard of theatre in London.

Oddly, the rows of women behind us, lubricated by white wine and stimulted by the on-stage abuse, responded frivolously with gasps and titters. Finally, the audience applauded and cheered the curtain line-up while Mike and I ran up the aisle and fled from the theatre.

My rating – Act One: ★★ / Act Two: minus ★★. I think that makes zero stars.

Group Appeal: 0 ★

09/10/24

Giant

By Mark Rosenblatt, at the Royal Court

Photos: Manuel Harlan

09/10/24 Mike writes –

The Turn of the Screw

An opera composed by Benjamin Britten with libretto by Myfanwy Piper, at the London Coliseum. (We saw a dress rehearsal)

My First encounter with Henry James’ novella, The Turn of the Screw (1898) was the film version The Innocents (1961) with Deborah Kerr and Michael Redgrave, adapted by Truman Capote and directed by Jack Clayton. It remains a classic of the genre, its widescreen black&white photography being a perfect means of drawing us into its story, creating the Gothic Horror atmosphere, and letting our imagination do the rest. Do watch it if you can – see details at foot of this review.**

With its tale of two children possibly possessed by the evil spirits of two adults, I can understand Benjamin Britten wanting to turn the novel into a claustrophobic chamber opera (1954) – those innocent young voices, the underlying suggestions of an illicit affair, the possibility of abuse, and as a central character a flaky female with what this century is called a Mental Health Issue. The narrator is the Governess, summoned by the children’s uncle to look after them, and telling us in a letter her disturbed thoughts of what she perceives to have happened.

The opera is set in a sanatorium ward and flashes back to the country house where the valet Quint (there’s a name to freeze the blood!) maybe dallied with Miss Jessel, the children’s previous governess. These lovers are now both dead, but the children are still under their perverting influence. Perhaps.

In the book, in the film, we can be manipulated by suggestion, presentation, and sudden surprises. This is not so easy when all can be seen literally on a wide stage in real time. Here the sanatorium with beds and nurses, doors and high windows, and a huge sliding wall, is always in front of us. Video images of the country house, with elaborate rooms, corridors and gardens, trees and gravestones, are projected over the whole set. I did not find this an appropriate staging – it disatracted attention from the narrative and the performers. The expected ‘face at the window’ moment is poorly staged and there is never any sense of sexual tension.

The music, of course, is Britten, beloved by many, and I guess for many that overrides my visual niggles. The outstanding performer was the Governess, (Ailish Tynan*), a beautiful voice, which the handout helpfully calls a Soprano yet unhelpfully fails to name! A small orchestra did Britten proud but a smaller theatre and a simpler setting would have helped the experience, helped our grounded imagination to soar.

As an old friend once told me, I don’t want to just listen to an opera with my eyes shut. Or is that how ghost stories should be experienced? To be fair, we could certainly see where the dear old ENO had spent its precious grant, but not wisely.

Our rating: ★★★ Group appeal: ★★★

Photos: Manuel Harlan

*The ENO excels with its website advertising, dropping the names of Bronte and Hitchcock, as well as cast names. “One of the most unnerving of all operas” we are told, to raise our expectations and perhaps bring in a new audience not knowing Britten’s reputation. For your info, there are only seven performances, with £10 seats at each performance, free admission for Under 21s, but with the top price varying from £160 to £195 on different days.

**This summer (and I quote YouTube) “an amazing 4K remaster of 1961’s classic movie The Innocents, has been added to YouTube. This is a shockingly wonderful AI remaster of the movie which makes you feel like you are watching it for the first time. Details pop out at you and the film’s incredible atmosphere is amplified.”

This film (please NOT the 2009 version) is currently available on YouTube at this LINK. Watch it on tv if you can. There is also a hysterical trailer at this LINK, which is fun but not a good representation of the film!

05/10/24 Fredo writes –

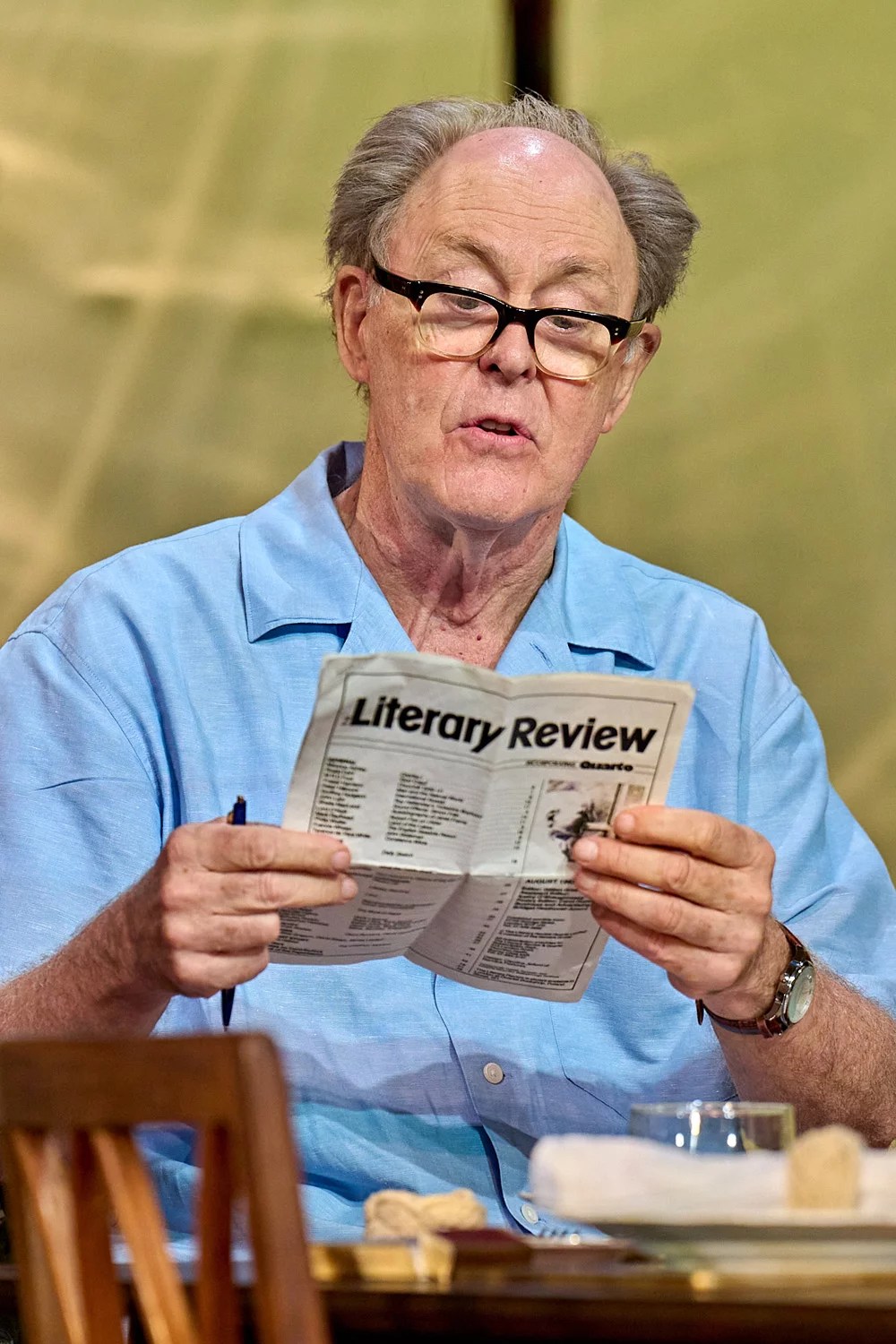

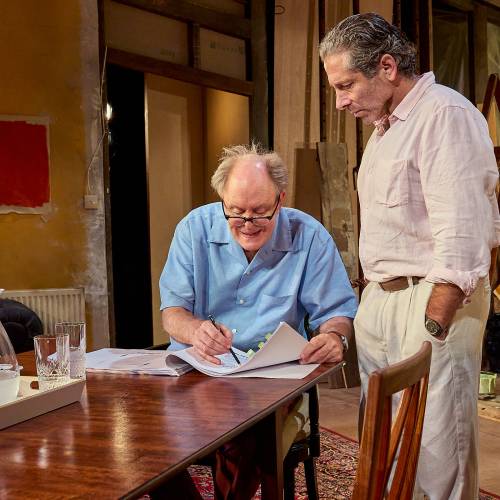

Coriolanus

by William Shakespeare, at the National: Olivier Theatre

A lot happens in Coriolanus: I find it absorbing. It’s action packed, the language is vivid and easily to follow, especially in this well-spoken production. The Roman citizens are dissatisfied – they’re hungry, and the Senate are withholding corn; there’s a war with the Volscians, and the leader Caius Marcius is a hero, but he’s arrogant and he despises the people. Despite this, he’s appointed Consul, but the rabble turns against him, and he defects to the enemies of Rome. There’s no sub-plot to distract us from the main action.

Like Julius Caesar, the politics of the play remain relevant to any age, and uncomfortable comparisons can always be drawn to the whatever government is in power in any part of the world.

Perhaps Shakespeare spends too much time on the narrative. Major battle scenes take place at the start of the play, before characters are fully established. Perhaps we expect Caius Marcius, soon to be given the title of Coriolanus, to be presented more sympathetically. Perhaps that’s why it remains one of Shakespeare’s least popular plays. Mike liked it less than I did, and a friend who sees everything at the National hasn’t booked, as she dislikes the play.

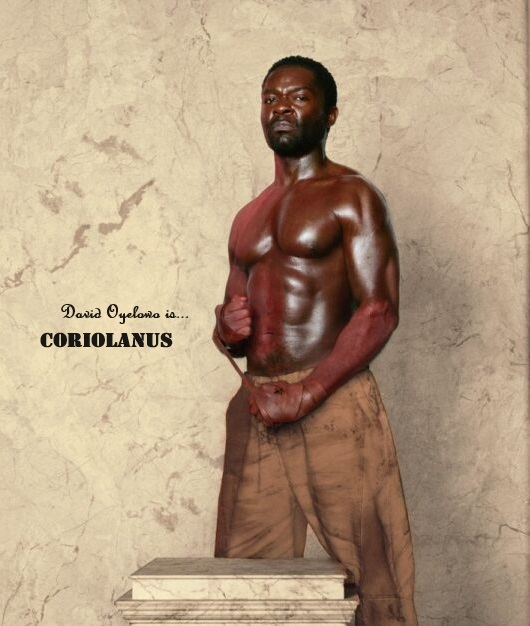

David Oyelowo who in real life is a Yoruba prince*, is a charismatic Coriolanus, and caries the frame on his muscular shoulders. The National Theatre’s poster shows to advantage that he looks as though Michelangelo had freshly chiselled his body out of black marble. He takes in his stride the difficult transitions from the reticence of Coriolanus in showing off his wounds in the market-place to his explosive rejection of the state in his great speech, “You common cry of curs, whose breath I hate.”

Such a performance needs to be shown off in a glittering setting, and director Lyndsey Turner has ensured that he is surrounded by strong performances from Peter Forbes as the reasonable Menenius and Kobna Holdbrook-Smith as Coriolanus’s opponent Aufidius. However, the ultimate nemesis of Coriolanus is his warrior-like mother Volumnia – a merciless portrayal by Pamela Nomvete, as much on fire as she was in the Donmar’s recent Skeleton Crew. and there’s a very eye-catching turn from Jordan Metcalfe as a prissy Brutus, one of the tribunes.

The set design by Es Devlin is handsome, with Roman artefacts displayed on plinths. This prompted Mike to speculate that it was set in the British Museum, or even the British Museum shop. I would never make such a cheap jibe, though Lindsey Turner acknowledges this by staging a joke about it at the play’s end.

For me, it was a triumph, and the best production I’ve seen at the Olivier for some time.

Our rating: ★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★

This might have been difficult to sell. Despite his appearances in Spooks, Selma and A United Kingdom, I’m not sure that David Oyelowo has the name-recognition he deserves.

(Photos: Misan Harriman)

*David Oyelowo was born on 1 April 1976 in Oxford, Oxfordshire, to Nigerian parents. His father, Stephen, is from Oyo State, South West Nigeria, while his mother is Igbo from South East Nigeria. Oyelowo is an omoba (or prince) of the Yoruba people in the Nigerian chieftaincy system, his grandfather having been king of “a part of Oyo State called Awe”. He has commented on his background: “It sounds way more impressive than it actually is. There are so many royal families in Africa”, “royal families are a dime a dozen in Nigeria”; “what we think of as royalty in the UK is very different to royalty in Nigeria: if you were to throw a stone there, you would hit about 30 princes. So it’s a bit more like being the Prince of Islington: it was useful for getting dates but probably not much else”. See Wikipedia LINK for full bio.

03/10/24 Mike writes –

Hadestown

Book, Music and Lyrics by Anais Mitchell, Developed with and Directed by Rachel Chavkin, at the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue

We last visited Hadestown a while back on the South Bank. Since then Orpheus and Eurydice have been travelling, not to the underworld but across the pond to Broadway. In fact they have been travelling in one form or another (including a concept album and various US destinations pre-South Bank) since 2006. I guess they are satisfied with themselves now, and have gathered groupies along the way. The West End cast is about to change so we were invited to see them before some new members take over.

First on stage comes Hermes (Melanie La Barrie) a white-wigged besuited West Indian woman who flashes her sparkly waistcoat at us. And then she does it again to get a bigger cheer. I disliked her from the start, her attitude, and especially the response of the audience who were already hyped up and seemed to be Best Friends with all the cast who had yet to do anything. I felt I had come to the wrong reunion party!

Eurydice (Madbeline Charlmagne) is a poor black soul, wise but weary, but then a naive and poetic white Orpheus (Dylan Wood) appears with curly hair and guitar to sing his La Da-Da Daa, Da-da Daa song to her and us all. The La Da-da Daa-ing was very Song on the Sand so maybe he had seen La Cage Aux Folles. But he soothed my irritation and charmed everyone else.

There was little pause for breath or romance because the show is sung-through and seems set in a bar ruled over by a white Mr Hades (Zachary James) and his floozy black partner Persephone (Gloria Onitiri), both adept with a microphone, supported by five mixed-race mixed-gender heavies in leather, tatoos, and designer zips straight from Mad Max. Anyway, Eury succumbs to the bass voice and basic appeal of Mr H and he invites her upstairs, which appears to be downstairs as it’s the Underworld. Cue for Interval and the stage lift to descend, leaving Orph in a predicament and us grateful for the break.

You know what happens, but nevertheless I wondered how the well-known turn-around would still send us home happy, maybe moist-eyed and morally uplifted. Obviously the show delivers sufficiently for it to have an enthusiastic following and its cast work energetically for their applause and cheers.

I did rather enjoy Act 2, was particular impressed with the leads, but unimpressed by one of a trio of Fates, who kept a fixed expression of bored distain on her face throughout. Of course I cannot remember a single song…..except that La da-da daa, da-da daa, which wormed its way into my subconscious for days. I guess the writers would regard that as success.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

Photos: Marc Brenner

01/10/24 Fredo writes –

Billy Stritch

In cabaret at The Crazy Coqs

You may not have heard of him, but Billy Stritch has been around for years, and 23 of those years were spent as Liza Minnelli’s pianist and music director. He’s a big name in cabaret, especially in New York, where he’s highly regarded as a composer, arranger, singer and jazz pianist. He’s a doyen of cabaret artists, and that why we were keen to accept an invitation from our friends Jan and Michael to hear him at Crazy Coqs. And no, he’s not related to that better-known Stritch, Elaine.

This, he told us, is his 11th visit to Crazy Coqs, and word had got around. Anne Reid was there with a large contingent of friends who just kept arriving, and as a cabaret afficionada, she drank in every note from her front-row vantage point.

He’s a musician’s musician, and in his generous programme of 18 songs, the show-biz patter was kept to a minimum. No mention of Liza, but a tribute was paid to Bobby Short, the legendary entertainer from the Cafe Carlyle on Madison Avenue (see Woody Allen’s movie Hannah and Her Sisters for a cameo appearance).

Instead all the composers and lyricists were acknowledged, and Mr Stritch skilfully arranged a programme of lesser known songs by the great composers: So Many Stars by Sergio Mendes, Last Night When We Were Young by Harold Arlen and Why Should I Care? by George and Ira Gershwin. Even the more familiar material was given a fresh burnishing in his mellow tones, and Let’s Take a Walk around the Block and Up On The Roof sounded brand new.

It was a relaxed performance, and Mr Stritch and his bass player Pat O’Leary seemed to enjoy themselves as much as their audience.

They finished with a rendition of A Nightingale Sang in Berkley Square that sent us back out into Piccadilly with a warm glow.

Our rating: ★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

(Crazy Coqs is not for large groups, so you must take yourselves!)

26/09/24 Margaret writes –

Shifters

By Benedict Lombe, at the Duke of York’s Theatre

Photos: Marc Brenner and others

Shifters, directed by Lynette Linton, has received very positive reviews from the UK press since its initial run at the Bush Theatre and it proved to be a thought-provoking and moving experience. The label “rom com” has been used by several critics but that really underestimates the power of the piece which tenderly explores themes of love, loss, destiny and disappointment. Certainly the narrative thread, switching abruptly back and forth, is about a relationship between a young black man and woman but there is so much more nuance than the conventional preoccupation of will they/won’t they live happily ever after?

There are just two characters: the feisty woman Des, short for Destiny, and the diffident, tender man Dre (short for Dream). They met a decade and a half earlier as sixth formers and the play moves between events from their past to the present day where they meet again at Dre’s grandmother’s funeral. He has built a successful business staying in their home town whilst Des has moved away, travelling to other countries to further her career. They shared common experiences as youngsters and these are subtly revealed through the play. A significant theme is the early loss of mothers and, later, fathers, and the role of women in binding together communities. The death of Dre’s grandmother brought Des back from New York to mourn her.

The largely black audience was very enthusiastic and involved with the characters and their obvious love for each other that is mainly unspoken except at some key moments. One electrifying kiss had the audience cheering. The actor playing Dre (TosinCole) brings a gentle longing that beautifully complements Heather Agyepong’s spikier Des. They are both rounded characters and the actors wring so much from the text that we become readily immersed in the emotional tension between them. There were plenty of lighter moments too although some jokes were lost on us as they were specific to West Africa culture, the heritage of Des and Dre.

The music and dramatic lighting added to the tension of the present day scenes as time was running out before Des had to catch a plane back home.

Shifters is well worth seeing. Tosin Cole and Heather Agyepong are very talented actors and the text and direction compelling. Recommended!

Our rating: ★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★

(A white audience may have less understanding of the language,

accents, and cultural references.)

25/09/24 Fredo writes –

Here In America

By David Edgar, at the Orange Tree Theatre

“Being in America during the latter stages of a Presidential election is like being in a pressure cooker without being sure what is being cooked.” – So says journalist Ruth Leon, commenting on her current visit to New York, though I suppose you could say the same thing about elections in any country, any time. It makes us long for more carefree, innocent times. But was the mid-20th century any more innocent?

In his new play, political dramatist David Edgar suggests not. Based on the real-life conflict between playwright Arthur Miller and stage and screen director Elia Kazan, Edgar examines the pressures, compromises and treacheries that prevailed during the Communist witch-hunt of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in the early 1950s.

The pair, whose backgrounds are so similar that Kazan’s wife Molly comments that they could be the same person, fall out over Kazan’s capitulation in naming names of Communist Party members to the Committee. It’s a clash of ideals and principles, argued passionately and intelligently by Edgar. There’s an urgency about the play: attention must be paid.

I have a head-start here, as it’s familiar territory for me. Miller is one of my favourite playwrights, and his autobiography Timebends is a book I frequently return to. I grew up watching Kazan’s movies (On the Waterfront, East of Eden) and I’ve always had an interest in the HUAC activities. I already knew the information that has to be relayed in the exposition that occupies much of the first 20 minutes of the play, but Edgar drip-feeds it in gracefully, and it’s delivered with matter-of-fact intelligence by Faye Castelow as Kazan’s wife Molly.

In fact, intelligence is the keynote of the play. These are thoughtful, articulate people. Even the presentation of Marilyn Monroe by Jasmine Blackborow is refreshingly as an astute person who knows what the score is in this uncertain time. She may be willing to slip between the sheets with Kazan while she’s engaged to Joe DiMaggio, but Kazan’s betrayal of his friends and colleagues is shown as the greater evil.

As Kazan, Shaun Evans (Endeavour) gives a nuanced performance of a character who has already had an unfavourable verdict in the history books. He shows an unease yet a willingness to shrug off the moral responsibility of his actions. He’s well-matched by Michael Aloni, making his British stage debut as Miller. This is a cleverly calibrated performance, and Aloni’s delivery of the dialogue is masterly. When Kazan accuses Miller of not quite having the blameless integrity that he claims, there’s a hint in Aloni’s portrayal that Miller himself shares that view.

Although the historical events of the play are familiar – Kazan, named names, Miller didn’t, then Miller wrote The Crucible in response to the hysteria of the time, and he and Kazan didn’t speak for 10 years – Edgar creates a dramatic arc to the narrative that holds our interest.

The play ends on an unexpected (if you haven’t read the books) note of reconciliation: Miller asks Kazan to direct his latest play, After the Fall, the one that covers his marriage to Marilyn. But Edgar slyly presents us with another example of Kazan’s treachery. Kazan introduces the actress playing Maggie (the character who is based on Marilyn in Miller’s play) to his own wife. The actress is the aloof and slightly off-hand Barbara Loden, and there’s tension between the two women. Barbara Loden later became the second Mrs Kazan!

Photos by Manuel Harlan

You can tell I loved this play. It’s tightly constructed, and the staging by director James Dacre is unfussy and economical. It ticked a lot of boxes for me, but I’m not sure that other audiences wouldn’t want a more expansive exploration of the subject. The audience we were with enjoyed it, and the actors knew it – Shaun Evans gave Micael Aloni a discreet wink as they took their bows.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★

18/09/24 Mike writes –

Why Am I So Single?

A big fancy musical by Toby Marlow & Lucy Moss, at he Garrick Theatre

(We were invited by Delfont Mackintosh)

Why Am I So Single? Or as Fredo so wisely asked “Why are young people so self-pitying and self-indulgent?” The second question perhaps answers the first. Here we have a musical catered to those still hungry for Six, by the same writers seeking a second box office success, now supposedly writing a musical about themselves.

It had to be another on-speed musical, lyric heavy, but this time without Henry VIII providing the plot. They have reinvented themselves as typical of their audience, young, aggrieved, and asking that title question. There’s Nancy the female singleton, and there’s Oliver the gay lonesome ‘they’, bosom buddies seeking the loves of their lives. Note their names, taken from Lionel Bart’s Oliver! – oh, the cheek of it!

The script is knowing, repeatedly answering its own question, but still thinks it is worth asking. The obvious answer, they finally decide, comes in a song – “Men are Trash!”. (Maybe nothing rhymed with the fashionable ‘toxic’ – no wonder they are single!) But there are some good songs which would fit better in a different context and sung with less of the desperation to be show-stopping. The choreography is frenetic, but best is a number in tap-trainers with Noah Thomas leading the ensemble who play everything from mates to animated home furnishings (yes, really, it’s that sort of an aren’t-we-having-fun show).

I assume by their behaviour that the cast are meant to be teenage-ish, but Leesa Tully (or did we see Collette Guitart, the understudy?) is oddly miscast as a too-old Nancy. She is very much the straight foil to Jo Foster who steals every scene as the waspish and eternally juvenile Oliver. His/their campery, prancing and posing in a skirt and fluffy pink slippers, is continually OTT; he’s a charmless cousin to the Jamie ‘everyone is talking about’. The audience loves both Nancy and Oliver, especially with their carefully rehearsed ‘impromptu’ winks and quips to us, their new best friends.

Tv’s iconic Friends comes up as a role model for this bunch to both copy and ridicule, and it seems to be a hook to involve both the audience and the young characters alike. It’s a show not for my generation, I’m the wrong demographic, so excuse my miserable response. The audience guffawed, they whooped and cheered, they clapped and hollered, even during the songs. It’s a hit, of course, but would be a much better show with a whole hour plus the Interval cut from it, making it just like the slick but mighty 90 minute Six, still wowing the world.

This one calls itself “a big fancy musical”, but I don’t fancy the show, nor even any of the cast. And I doubt it will be as big as Six. Writing a second show is always a mountain to climb, but this one stays stuck in camp.

My rating: ★★

Group appeal: ★★★ (but only if you are young, on a first date, and really really want to see it.)

Fredo adds: Mike is being uncharacteristically charitable about this show. The choreography is good, at least in Act One, but the songs are just noise with incomprehensible lyrics. I hated the performers, with the exception of Noah Thomas. The cast and creators must be exhausted from patting themselves on the back, another form of self gratification, which is all this show amounts to.

31/08/24 Fredo writes –

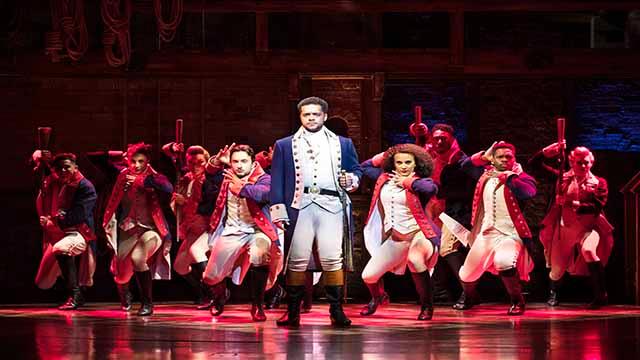

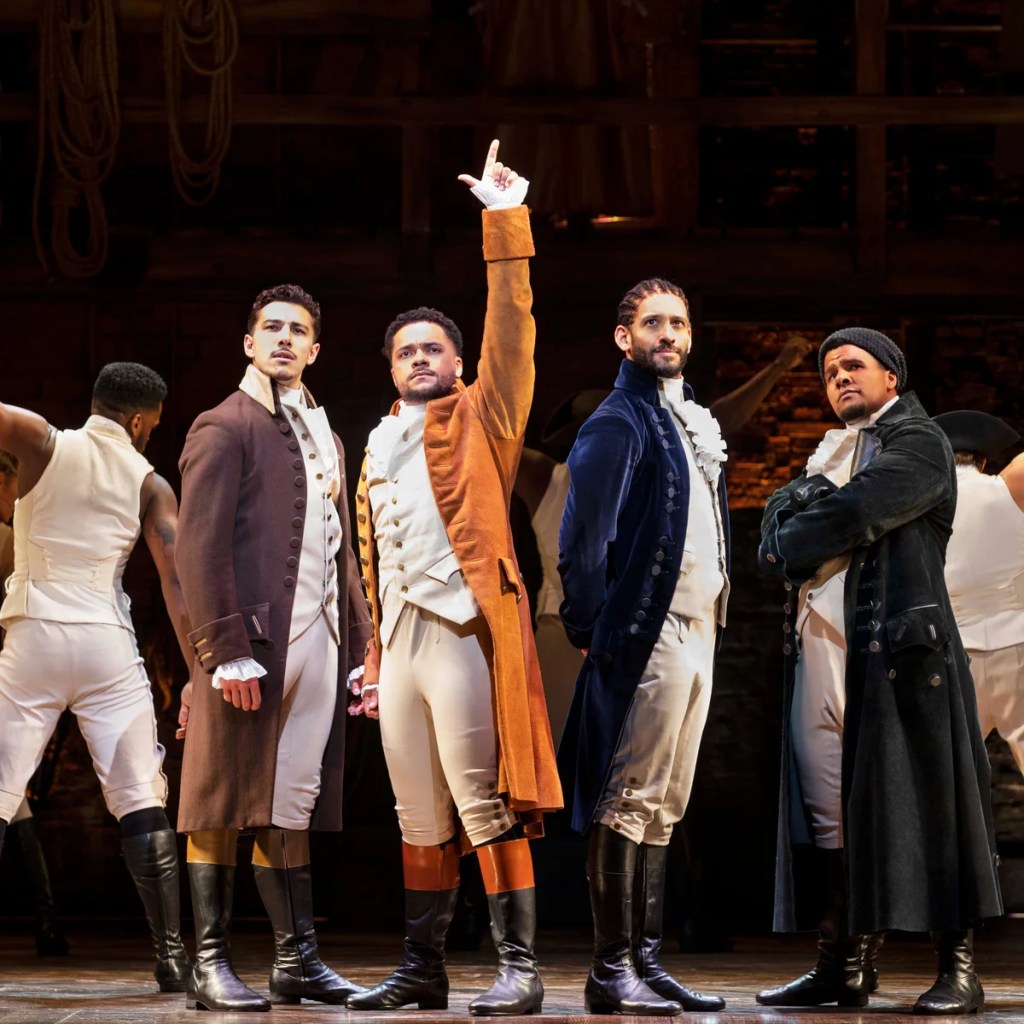

Hamilton

Music & Lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda, at the Victoria Palace Theatre

“Every song is a banger,” the young man next to me commented to his girlfriend at the interval. I was relieved to know that they were still enjoying themselves, as I thought I’d just ruined their afternoon. I’d revealed that I’d paid £42.50 for my ticket on the day, while they had paid £100 each, in advance, for theirs!

Yes, I’m late to the Hamilton party, but I didn’t realise quite how late. Heavens, it opened in 2017! And I’m someone who claims some knowledge of American musical theatre, and I hadn’t caught up with this reputedly groundbreaking show.

I had good reason. The show arrived with the sort of fanfare you’d expect for the Second Coming. The theatre sold out for months, and to prevent black-market ticket sales, you had to pay a booking fee, queue up at the theatre, produce your passport (yes, really) and claim your tickets. And no group reductions, of course. I postponed my visit till the hysteria died down.

Then when Mike and I got round to booking, there was a mix-up over the dates, and I couldn’t go. I contented myself by reading Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton instead. And then I sort of lost interest.

Until last Saturday, when I fund myself at a loose end, and I took my chance at the Victoria palace box-office, prepared to sit in the rafters if necessary, just to be in the room where it happens. Instead, I was offered a choice of seats in the rear Stalls or the Dress Circle, at what turned out to be a bargain price.

Was it worth the wait? Absolutely! I was prepared for the edge to have worn off the performances, but the entire cast performed with precision and commitment; it might have opened last week. (I discovered later that a new cast had taken over in June).

(Photos are of this production but not of the current cast. The individual photographers are unknown.)

It’s a wordy, narrative-heavy show, and Lin-Manuel Miranda doesn’t short-change us on detail. The genius of the lyrics lies in his ability to select the salient details, look at them from a contemporary perspective, and translate them into a modern idiom. No, I didn’t follow every word, and there were times I lost the thread of the political machinations that were developing on stage (and in truth, I found that part of the book hard work). I was able to forgive that, because the story-telling on-stage is so dynamic. The restless cast is constantly in motion, with some of the most complex choreography that I’ve seen.

Most of the songs have an irresistible hook, and there are so many of them (nearly all bangers) that none settle in your ear for very long.

The success of Hamilton rests on the creators’ courage in maintaining a consistent idiom to tell the story and, while embracing rap as a means of telling the story, they never dumb down their narrative. It’s a triumph, and deserves its success.

My rating: ★★★★★

Group appeal: ★★★? You tell me: don’t be put off by the preponderance of rap. There’s a lot of detail to follow but the sheer spectacle carries you along. I’m sure a lot of our group may have gone independently, but I’d be happy to organise this if enough people still want to see it.

29/08/24 Mike writes

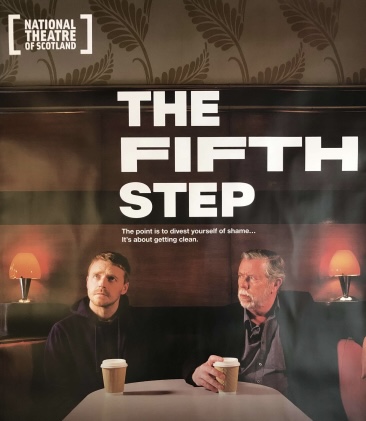

The Fifth Step

By David Ireland, at the Pavillion Theatre, Glasgow.

As every alcoholic should know, that fifth step on the road to recovery is owning the mistakes you have made, facing up to the past before facing the future.

Luka is at the start of his possible abstinence and James is the older sponsor who knows that road, helping him to quit. It’s a serious business, and author David Ireland obviously knows that road too, but has no intention of giving us any earnest docudrama.

The opening words surprise us and the house erupts in laughter. From then on it’s a seriously funny play with its central theme jostled and disrupted by side-notes on male/male bonding, honesty and deception, the generation gap, sexual attitudes, masturbation frequency, religion, class, porn, and non-alcoholic beer. It’s straight talking enriched with life’s idiosyncrasies.

Photos: Mihaela Bodlovic

The scenes change, revolve, and are eventually deconstructed in much the same way that the central AA situation is digressively pulled apart. Finally, the resolution may not bring total dramatic satisfaction but the journey there has been a vicarious roller-coasting ride of revelation and duplicity.

It was certainly Jack Lowden (from tv’s Slow Horses etc etc) who filled the theatre, but together with Sean Gilder the duo are a class act of perfect timing, alternating their straight/comedy balance, and surprising us at every sudden change in the direction this dark comedy takes. Lowden excels at being both gormless and witty at the same time while Gilder is the steadying one gradually falling apart.

With an initial run of just a few days each in Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, it would be a pity if only Scotland is treated to this 90 minute gem. It deserves a London visit – we have alcoholics here too! I suppose Jack Lowden is not available for a long run, but even recast it would be worth greater distribution. The audience loved it, loved the two of them, and so did I.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★½

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★

24/08/24 Mike writes –

Our House

Book by Tim Smith, Music & Lyrics by Madness, at the Southwark Elephant Playhouse

All credit to the National Youth Music Theatre for its production of the Madness musical at the Southwark Playhouse. With a madly short schedule of rehearsals, a large cast of talented youngsters with an unconfined abundance of enthusiasm, have achieved an infectiously joyful entertainment.

These guys and gals (aged between 12 and 23 their website tells us) are non-professionals just starting out on possible musical careers. Their promise is already leading to achievement. Whoever is responsible for the casting, they have chosen well. If any allowances have to be made, it’s the suspension of disbelief when one young generation has to play both teenagers and parents, but even here their presentation passes muster. And the majority of the young cast excel as a motley group of exuberant school-kids.

In the lead, as 16 year old Joe on his first date, is Des Coghlan-Forbes; he can sing, he can dance, he can do anything, with a relaxed presence, either sharp or charming, depending on the ever-changing positive/negative scenario; and importantly he can manage his costume changes in seconds. Sara Belal is Sarah his girlfriend, the steadying influence, and brings warmth and a good voice to her role.

Without a complete cast-list to hand, many others make their mark but have to be unnamed, including the young women in a variety of smaller roles, and Joe’s peers all with their individual quirks.

The group Madness wrote most of the songs ‘back in the day’ and here, just like Mamma Mia, they have been woven into the fabric of a family saga of young love, growing up, and its many tribulations. It’s a two-sided plot, showing the either/or of what might happen when a first date goes very wrong….or right. We first saw this show 20 or so years ago, and I loved it so much I bought the double CD of the Madness songs (included here Driving in My Car, Baggy Trousers, House of Fun, and of course Our House).

Photos: NYMT website

They don’t date, they just become part of the national consciousness and the kids here perform them with energy and a gleeful gusto, amazingly choreographed in the small space of Southwark’s Elephant (& Castle) theatre. Every upbeat number or heartfelt ballad is performed with confidence and understanding, no mean feat for newcomers with their audience clustered around on three sides. Congrats to every one of them. And unseen but of huge importance, ‘the band’ is also young, amateur and….no-one would guess. Even those in the audience NOT friends and family of the performers, had a great time. Just a total joy.

Our rating: ★★★★ / Group appeal: ★★★★

15/08/24 Mike writes –

The Years

Directed by Eline Arbo, Adapted as De jaren by Eline Arbo, in an English version by Stephanie Bain, Based on Les Années by Annie Ernaux, at the Almeida Theatre

We Need To Talk About Annie. We really must. Annie Ernaux has written many non-fiction books about herself, her life’s joys and troubles, with her book The Years being published in France in 2008; she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2022, aged 82. All this now culminates in the play of the book(s), first seen in Amsterdam and now at the Almeida. It’s been adapted and directed and translated into English by two other women. It can fairly be called ‘a woman’s play’, as we might have once said, though the meaning now is quite different from what the phrase used to mean. Here Annie’s life is politicised so she becomes Everywoman, reflecting the cultural, social and sexual chapters in every woman’s life. She is even played by five female actors at different ages, who also represent the male characters, and they all want us to talk about Annie.

Left picture: Deborah Findlay / Anjli Mohindra / Gina McKee / Harmony Rose-Bremner / Romola Garai

And everyone is talking about Annie or, more correctly, about Annie’s abortion, because headlines have been about audience reactions – pass-outs, shout-outs, walk-outs, by men as well as women – due to this detailed abortion scene. You may quibble about its bloody presentation, and certainly its detail can be very upsetting for some, but there is also fun in Annie’s life. There’s humour and honesty too, so I can understand women who feel they are well represented in all quarters. It’s just a pity that the abortion scene is getting all the publicity. There were no interruptions during our matineé performance.

But as a man, do I flinch, empathise, disagree or admire? Or do I just dismiss it as ‘a woman’s play’? No, and I think this is due to the energetic and appealing performances, and also the way they have been directed as an ensemble, which even we men can identify with. We don’t have abortions (this week it’s reported NHS forms now ask male patients if they are pregnant – yes really!) but men are often the other half of many women’s relationships and we have equal traumas, excitements and amours. Talk of toxic masculinity if you must (many do but the five here don’t); however, they do talk a lot about finding their freedom from the pressures of our society’s expectations.

Annie does indeed find her freedom, after youthful sexual experiences with and without men, after that abortion, and after marriage, births and divorce. But by then she has two teenage sons, and ironically longs for love and a male lover again. Society has changed so much during her life, but human desires remain much the same. By the end a warm tranquility has descended on Annie’s final years, and on us who have witnessed life’s ups and downs with her.

Her journey is told through photos, as if from an album, but instead of pictures we are given live portraits posed against white tablecloth backgrounds. Those tablecloths are well used as props in all scenes, getting stained (paint, blood, wine) and discarded before becoming triumphant banners at the finish. Props revolve on tracks; the times, from mid-twentieth to early twenty-first century, are signposted by evocative music; the cast wear timeless pants and tops; and the atmosphere is festive.

After two uninterrupted hours this whole life has reflected our lives too, through one gender specific biography. The five Annies have befriended us, have enthralled us with their up-front truths and entertaining presentation. Five hurrahs for the five ages of Annie.

Our rating: ★★★★½ / Group appeal: ★★★½

10/08/24 Kathie writes –

When It Happens To You

By Tawni O’Dell, at the Park Theatre

A heading in the programme reads ‘Re-Staging Trauma: The ethical questions of dramatising violence and pain’. The prolific coverage in the media about Amanda Abbington and a certain dance show might have a similar theme but leaving all that aside we were there to see this ‘theatrical memoir’ as it’s been termed, first performed off-Broadway in 2019 with the author/playwright herself in the principal role. Park Theatre’s main stage, seating 200 in two tiers but just 3 or 4 rows enveloping the thrust stage, provided a very up close and personal setting to bear witness to this depiction of a true story.

The core of the story is about rape and its impact on the individual and everyone around the victim. A mother (Tara) is woken by a call from her daughter (Esme), living in New York, having been followed home and attacked in her flat. The medical and law-enforcement repercussions are presented as efficient and sympathetic, the perpetrator caught and prosecuted. As satisfying as that might be, it can’t diminish the mental and emotional fallout. The mother is desperately trying to help and there is a son/brother (Connor) away at university who does what he can, when he can, but feels inadequate and excluded. A fourth actor plays all the other characters that we meet which help define where and when we are in the narrative.

It’s a sparse set with no furniture or props, other than the odd device used by the fourth actor, such as a badge or a stethoscope, to fit with that character. The tale is delivered mostly as a narrative by Tara directly to the audience with particular scenes enacted for us which succeed in giving greater substance to that incident or moment. There is an odd interjection of light or even humour, which is laudable to give pause to the unrelenting grimness, but not always successful.

The fact this story has been written and dramatised emerges as a means of being more open and honest than can be achieved by merely talking. There is a shocking twist in the tail, with the whole event rounded off with facts and statistics about the incidence and effect of rape which provoked a profound response in most of the audience.

Amanda Abbington, as Tara, gave an admirable performance and the depth of emotional involvement at the end seemed to go beyond acting. Esme was played by Rosie Day and she was suitably fragile, angry and hurt but lacked some vulnerability perhaps. Miles Molan as Connor has the least interesting character though, being true to life, the fact that men are part of the family means his response is valid and should be represented. Tok Stephen filled all the other parts and did so impressively.

Overall, this seemed a bit of a hybrid between fact and fiction but it certainly filled its 90 minutes on stage with a powerful story that should be told.

Our rating: ★★★★ Group appeal: ★★★½

Photos: Tristram Kenton

04/08/24 Mike writes –

Red Speedo

By Lucas Hnath, at the Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond.

I’m being maligned! Some are saying I only booked Red Speedo to see Finn Cole (from tv’s Peaky Blinders and making his stage debut here) in his…er…red speedos! Well, maybe, but the play has other credentials – it is written by Lucas Hnath, author of A Dolls House: Part Two, seen previously at the Donmar and highly praised, by us and others. And Red Speedo has been welcomed in reviews and is a sell-out for the tiny Orange Tree. There are photos here to help you judge!

Photos: Johan Persson

The play’s theme is up there in today’s headlines. It concerns would-be Olympic swimmer Ray trying to qualify for the Games and find lucrative sponsorship, but with the assistance of illicit drugs. It’s a serious subject given a speedy run-around here with humour, conflicting characters, and an on-stage pool, small but symbolic enough to make a splash and keep our minds on the ‘winning swimming’ theme.