Additions from other sections of our website

15/07/25 Mike’s Opinion –

How woke is Theatreland?

This article began on our Home page and is continued in full here.)

It’s an easy assumption in the media that supporters of Woke are to the Left of politics and detractors to the Right. Generally the Guardian speaks for Woke and the Telegraph opposes. Art and Culture mostly lean to the Left, with Theatreland embracing Woke with enthusiasm. And if you’re unsure just what Woke is all about, then ask one of those Cancel Culture / Safe Space fans, those shrilling voices always telling us the right way to think. I’m more centre ground myself.

Of course we all want to be nice to each other and have others be nice to us; to care and be cared for. But do we need to be told, advised, protected, or even lectured? Politics, social problems or sensitive topics on stage, these we may seek out to applaud, or choose to avoid, but do we need full disclosure and protection before even entering the theatre? Theatreland thinks we do. For me, any instructions or advices come into the category of Trigger Warnings – an unnecessary intrusion into what should be both an entertaining and challenging environment. Theatre is Life, not a Safe Zone where we should be warned what to expect and how to avoid being affected, embarrassed or, heaven forbid, ‘upset’. A reflection of life, on stage, through different prisms, is my theatre expectation.

When choosing a theatre, do you worry about the Slave Trade? Scanning through those parts of theatre agency websites which are the small print, I was surprised to find at least one theatre agency says –

“We are continuously working to minimise the risk of modern slavery and human trafficking across our whole operation. Our Anti-Slavery Policy reflects this dedication and a copy of the policy can be found on our website.”

Really, I did not need to be told of a slavery policy. Does it help to salve anyone’s conscience on entering a theatre?

Speaking of Conscience – it was recently reported that Caryl Churchill withdrew a planned production at London’s Donmar Warehouse due to the theatre’s sponsorship by Barclays, citing the bank’s alleged links to defence companies supplying Israel. I’m not a fan of Israel’s government, nor Ms Churchill, but Caryl is shooting herself in the foot, and shooting us in our feet, by trying to ban Barclay theatre sponsorship. And don’t even mention Oil.

It seems others want instruction and reassurance on just entering a theatre…back in the small print I found info on –

“How to dress for a West End show: A guide on what to wear to the theatre. The simple answer here is (wear) anything…there are no dress codes”.

If you are a complete novice, it reassures you, but….surely smart casual is the bottom line? We don’t want beach wear and flip flops, do we? No advice is better than wrong advice. They continue with –

“Buy merchandise. Many productions sell official clothes and accessories in the foyer. Why not pick up some merchandise before the show and wear it in the auditorium?”

Hmmmm, yes, I see this is where business enters the world of Show Business.

Now let’s turn to Trigger Warnings which some theatres cutely call Sensory Advice. But where to start? Every show now has them so I will choose at random, the musical Hamilton, the big box office draw now well into a long run. Do you worry in advance you may be triggered by this show?

There are warnings –

Nudity/Sexual Content

There is no nudity, but a song detailing an affair between Alexander Hamilton and Maria Reynolds is shown from 1:29:21-1:33:17 with a sensual touch and a clothed lap dance…

Seriously?! If anyone is triggered or offended, they deserve to be, so don’t mention it.

Graphic Violence

The first duel implying gun violence (in which Hamiton and Burr are the duelling parties’s (sic) seconds) is from 0:48:39-0:50:25…

So turn away, if you have bought a ticket and feel a sudden turn coming on. The TWs give you the exact timing into the show when your trauma/objection may occur, or alternatively the time when you should protest!

Even the musical “Oliver!” has included trigger warnings for –

“depictions of violence, poverty, hunger and crime, as well as gunfire and smoke.” And unsurprisingly “the production uses mild and discriminatory language from the period”.

Is it not an education that discriminatory language from the period should be faced up to, not warned against and turned way from?

There is an abundance of cautionary TWs available – just check the website of any show before you risk entering the theatre. What sad souls need to heed such warnings? Too much protection!

Poor Shakespeare always finds himself the victim of trigger warnings. Back in his day, he was happy to challenge, entertain, thrill, outrage, surprise and educate his audiences, it was what they wanted, but nowadays Theatreland thinks audiences need to be forewarned. Warnings for Othello, as an example, can include –

“depictions of domestic violence, racism, sexual jealousy and murder”, as well as “the use of racist language”. Of course “depictions of violence” in his plays are often mentioned including, in Othello, “a strangulation scene”. (My apologies, if you didn’t know.)

Is all this really necessary? No, it’s not.

In NYC recently, parental concerns about anti-Semitic themes in The Merchant of Venice led to the cancellation of a school presentation. Can we not make up our minds after seeing the play, which surely depends on its actual presentation, instead of it being cancelled?

(If you get the chance, do check out Tracey Anne Oberman on tour playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice 1936, for an excellent reworking of the play.)

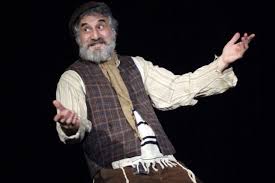

In a Q&A recently, the Jewish actor Henry Goodman explained that Shakespeare imbues Shylock with such humanity that he transcends any prejudice.

Are we now the most mentally fragile audiences ever? You tell me.

I do agree with age advice but parents should know what their children can accept. The problem is what the adult parents themselves can accept. Given a show’s advertisements, and background info easily obtainable on line, plus press articles, surely no-one needs those frequent popular warnings –

“contains swearing, smoking and sexual behaviour.” Etc, etc.

Is all this cosseting Care & Concern really necessary? I think not. You may disagree. But for me the whole theatre world has gone crazy over the Woke mindset. Let’s be done with it and live dangerously.

Happily, there are signs that the era of Woke is beginning to fade, both here and in the US: the Trigger Warnings for the upcoming production of Shakespeare’s Othello merely state –

“The play contains themes of sex, violence, death and themes related to mental health.”

Does that help you? Thankfully, nothing about strangulation!

Theatre portrays all aspects of life, and life on stage should not be sanitised or censored to protect the politically or emotionally over-sensitive. Be brave and learn to love the Theatre.

29/06/25

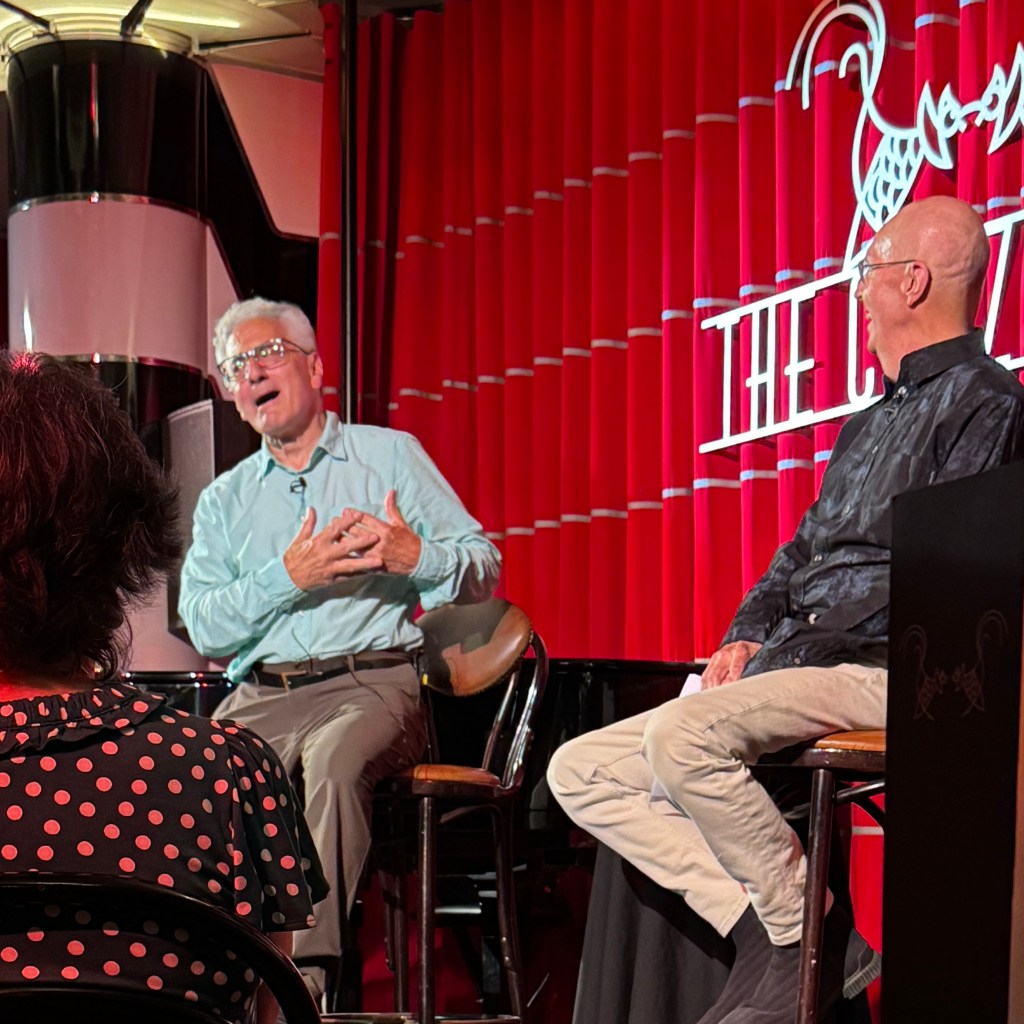

Henry Goodman Q&A – CONTINUED from the OnOurOwn page

…Yet there was another string to Henry’s acting bow: he considers the job of an actor to be on a spectrum from Priest to Peacock. Priest, because he is there to serve the writer and his text, to draw out the meaning and to interpret; Peacock, in order to entertain, to draw the audience, to give them the old hocus-pocus. He added that at RADA, this latter aspect came more easily to the American students. In fact he believes American and British actors differ – the British ones seek to draw the audience into their characters and situations to grip them, whereas the US ones want their characters to reach out to audiences and satisfy expectations.

I finally realised why I have always found Henry such a dynamic performer. It’s not just the careful line reading – I recall his voice faltering on Guiteau’s line in Assassins, “I want to be ambassador to France” which betrayed his sudden uncertainty that his ambition could be achieved. Then there was the blazing declaration as Roy Cohn in Angels in America: “I am not gay! I have clout. Gays do not have clout.” Contrast this with Guiteau again, dancing a cakewalk up to the scaffold and singing, “I am going to the Lordy“, or with his reaction as Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof to Motel the Tailor’s proposal to Tevye’s daughter. Edward played this for us; and Henry commented that while this could be just a vocal exercise in key changes, it was important to fill it with changing emotions. It’s Henry’s ability to use the peacock element to project the character’s emotion that exposes the rawness of the emotion that makes him such an exciting, edge of the seat performer.

We learnt about his career as a street performer at the Munich Olympics (when responsibility fell to them to entertain the Olympic crowds when the Games were halted by the assassinations) and later in South Africa (he’d fallen in love and followed his wife there). Returning to England, he joined the RSC and won his first Olivier Award as Best Newcomer. He caught the eye – and another Olivier Award, as Best Actor in a Musical, in Assassins, and then went to the National Theatre for Angels in America.

There was some tension here between the writer Tony Kushner and director Declan Donnellan. Angels had been performed in San Francisco, and Kushner had firm ideas of what he wanted. Eventually, an arrangement was reached whereby he didn’t come to rehearsals for several days, and this gave the actors space to make mistakes and ask questions. When Kushner returned, he was able to see the progress they had made.

Edward moved on to ask about Chicago, and Henry instinctively adopted a Fosse jazz-hands pose. He said that directors Ann Reinking and Walter Bobbie had been very severe with the cast and worked them hard. He praised the Germanic cabaret element that Ute Lemper brought to the show and how Ruthie Henshall’s English quality complemented this. There was one amusing episode. In the show, there is intentional tension between the two leading characters, Roxie and Velma, and the Daily Mail ran a story claiming that there was tension between Ute and Ruthie. Ute arrived at the theatre, brandishing a copy of the rag, demanding, “Stop the rehearsal! Who wrote this article? Did you write this article?” (An example of fake news? Henry suggested that the story may have been planted by the producers.)

Despite his prodigious talent, Henry’s career hasn’t all been plain-sailing. He went to New York to replace Nathan Lane in the role that had made him a legend, in The Producers – and after 4 weeks, he was fired. Henry said that this was a huge fall, and totally unexpected. He had arrived expecting to rehearse. The director Susan Stroman dropped by to say hello, and handed him over to the Assistant Director. The show had been running a year, and Henry was expected to step into Lane’s shoes, with the same moves and the same timing – “Stand here, cross to here, put your arm round him here.” During the four weeks he played Max Bialystock, audiences responded well with standing ovations – yet it wasn’t what the producers (or someone) wanted. He was fired after a Sunday matinee, and had to clear his dressing-room immediately, and leave the theatre alone while his name and pictures were being removed from the billboards and on Broadway.

His wife flew out to join him. The very powerful producer/director Hal Prince summoned him to his office to reassure him that his work was excellent. Prince hadn’t seen him in The Producers, but was familiar with his work in London – and was familiar too with the shark-invested waters around Times Square. He told Henry that he too had worked with impossible people on Broadway – Jerome Robbins, to name but one – and that he would recover from this setback.

Depression didn’t set in until he returned to London. I don’t know how an actor can deal with such a public humiliation. His wife Sue supported him, but only three weeks later, the producers of Chicago called him to say they wanted him to take over the role of Billy Flynn in Chicago on Broadway. He was astounded, but returned and played the part, then the following year was back on Broadway with Art, with Brian Cox and David Haig.

In passing, Henry spoke warmly of his co-stars Imelda Staunton (Guys and Dolls) and Juliet Stevenson (Duet for One). These two shows demonstrate his range, from the show-off Nathan Detroit in the former, to the almost passive role of the therapist in the latter.

Henry admitted, and Edward confirmed, that he had been extremely nervous before appearing before the small audience at Crazy Coqs. Once on stage, he relaxed and spoke articulately and entertainingly for 90 minutes. He gave us amusement, insights, and a whole lot of razzle-dazzle.

08/06/25

Group seating allocation – what you need to know (CONTINUED from the Home page)

How does Fredo allocate the tickets? First of all, he makes a plan of the tickets that have been reserved for us. Usually, some rows have uneven numbers, so single people and groups of 3 or 5 are fitted in. He checks for aisle seats – which are not always numbered 1 – and attends to “special” needs: people with walking difficulties or exceptionally tall people who need to stretch their legs.

Then there’s the task of reuniting groups of friends who may have booked individually. In the past, he has had to make sure to keep sworn enemies apart, but that hasn’t been a problem in recent years. He does this two weeks before the performance. As a number of tickets are posted in advance to people who meet us at the theatre, that’s why it’s difficult to accommodate special requests made at the last minute.

On recent group theatre visits I have sat in Stalls row R but also rows D and F and K, and in Circle row D. We refuse to accept seats with a “restricted view” or bad sight-lines, and try to accommodate special needs like end-of-row seats on request. Most theatre staff and booking agents are very helpful, even reseating some who may have personal difficulties. We are thankful of the contribution they make to our theatre visits, to our enjoyment of live theatre among a live audience. Sadly, not every theatre is the Donmar, where everyone is close to the action.

As a postscript, please allow us one moan. On current evidence the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, is not an easy theatre to book tickets for. It is ‘independent’, not affiliated to any official agent, and is frankly unhelpful, being restrictive in its attitude to group bookers. Booking for The Deep Blue Sea was farmed out to an agency with a restricted allocation of seats. The theatre box-office handled booking for Till the Stars Come Down themselves, and were super-difficult about allocating the seats and allowing extra tickets for late bookings. They refused to print the tickets, and in error twice failed to attach the ticket document to their email! They reverted to the agency to handle group bookings for Othello, but are only allowing groups on Monday and Tuesday nights, with a cap of ‘1 group of 30 tickets’ per night. All the group allocation is now sold out. Let us all hope they will soon learn the error of their ways and give more encouragement to groups.

24/02/25 Cecilia writes –

Mary Queen of Scots – opera (1977) by Thea Musgrave at the London Coliseum on 18 February 2025

Festen – opera (2025) by Mark-Anthony Turnage at the Royal Ballet & Opera House on

9 February 2025

Witnessing these two remarkable works on successive nights was a rich and powerful experience. Fifty years separate the composition of these operas and the treatment of their subject matter differs considerably. But both demonstrate that modern opera as a genre can oblige us to address painful contemporary aspects of human conduct – misogyny, child sexual abuse, racial prejudice, hypocrisy and more. Both have ravishing scores by highly experienced and sensitive composers and both offer great roles for fabulous singers. Musgrave wrote her own libretto, derived from a novel, in fairly conventional narrative form. Musgrave’s other operas include several in which a woman is the chief protagonist. For Festen, Mark-Anthony Turnage (b. 1960) has set Lee Hall’s adaptation of the Vinterburg/Rukov film (Denmark 1998) which is episodic, hovering between truth and fantasy. Turnage’s diverse operatic oeuvre includes Greek, The Silver Tassie and Anna Nicole.

MQoS

Royal courts, passé and musty as they may seem, have long offered to the creative arts a gripping whirlpool of power struggles, fleshly passions and brutal factions. And they still do, as the court of king Donald reminds us, though whether his will generate quite the bloody drama of Mary Stuart’s remains to be seen. The opera focuses on the few years between her return in 1561 from France to Scotland as queen (she was an infant when her father James V died) and her flight to England. At 18 she is already a queen dowager after the death of her husband king Francis II. She takes up the Scottish throne on the death of her mother, the regent, Mary of Guise. Here she is – young, culturally French, a Catholic – in an increasingly Protestant state, attempting to assert her authority over the variously ambitious, lustful, competing, misogynistic nobles around her – not to mention a rug-headed populace.

Thea Musgrave’s opera, first staged in Scotland, has now had its belated London premier. The veteran composer (b. 1928) was in the stalls on the closing night when I witnessed the performance.

Musically, she surely would not have been disappointed. In the pit, Joanna Carneiro commanded the wondrously rich and expressive score, responsive to the actions on stage with their volatile moods and atmospheres. Indeed, at moments, credible drama was surging from the orchestra rather more convincingly than from the stage.

That is not to downplay the vocal skills and power of the principals and ENO’s chorus. Heidi Stober was a vocally athletic Mary, both decisive and indecisive in her political and emotional struggles, fully meeting the composer’s demands. As the sinuous Earl of Moray, bastard brother of Mary, Alex Otterburn was perhaps tested rather more; John Findon as the beefy and rapacious Earl of Bothwell was entirely convincing; Mary’s feckless new husband, the Earl of Darnley (Rupert Charlesworth), displayed appropriate ambiguity; and as Riccio, Barnaby Rea caught the quirky nature of this key role as far as circumstances allowed. Darren Jeffery made an imposing Cardinal Beaufort. Alistair Miles as Lord Gordon brought maturity and orotund tones to a role that seemed initially peripheral but ultimately became decisive – he forces Mary into her English exile, there to suffer further trauma, while promising to safeguard her infant son, the future James VI and I.

The production by Stewart Laing (director and designer) is a minimalist affair in modern dress. Eschewing coronets and codpieces potentially universalises the drama of Mary’s tragic situation. But the concept needed more hard thinking-through. Some petty anachronisms remain – e.g. references to swords that on stage are pistols wielded by the menfolk. More problematic is that Laing nods only costume-wise to a venerable ENO tradition of making the arcane accessible, choosing to retain the whole historical mainspring of the action – bowings, scrapings, political and confessional disputes that are the stuff of the 16th century – perhaps assuming that audiences can supply their own contemporary references. That’s a challenge to our imaginations – Mary on first arrival has the look of a B-list celeb with big sunglasses and too much luggage.

Little use is made of the Coliseum’s extensive stage – some action is lined up against a modest fence above the pit or further back under a marquee which is piece by piece erected over the course of the lengthy first part. For the brief final act it’s been stripped back to its skeletal framework, where Mary’s final sufferings take place. O.K., it’s some sort of symbol, but positioning the earlier dancing and Riccio’s allure under it rather obscures their significance. Overall, it’s an unimaginative staging which does little to support or illuminate the story line.

Happily for ENO, the Coliseum was packed and enthusiastic, grateful to savour such a potent work at last.

Festen (“celebration”)

The opera shows how a 60th birthday party for a patriarchal hotel owner Helge can pan out. An arc of a concentrated hundred minutes takes us from droll genial hellos to the pit of horrific family secrets and back to (apparently) sunny farewells. Clearly such a mix of mirth and the probing of human depravity risks alienating audiences – but I felt that the handling avoided doing so. The piece is an ironic commentary on our society where great evils are too often complacently ignored.

No minimalism or cramped staging at the ROH. Richard Jones (director) has created (with set-designer Miriam Buether) a typically clever and colourful mise-en-scene. A huge cast (with some glittering names) takes over an extensive stylish hotel lobby before dispersing to their rooms – these are cleverly lit up in swift sequences where some of the chilling secrets and illicit liaisons are revealed. One of Helge’s children, Linda, has recently killed herself at the hotel, and her sister Helene searches for a suicide note. At the party, Christian, another sibling, openly accuses their father of repeated sexual abuse of his children when young, the reason behind Linda’s death. Meanwhile, the appalling fourth sibling Michael goes about his manic promiscuous business. If all this were not grisly enough, Michael leads a racist attack on Helene’s boyfriend, Gbatokai, in which the rest of the supper guests cheerfully join.

Helge and his wife effectively shrug off all the accusations. The guests too seem in denial, an indifference that may be the basic message of this work. That’s not the end of it, however, and ultimately for Helge there’s an ambiguous comeuppance. Linda’s ghost offers a consoling message, quoting Julian of Norwich’s “and all shall be well…….” The following morning, there’s a witty reprise of the opening scene, the smooth friendly farewells suggesting that nothing of remark has happened. What was true, we ask, what really happened?

This outline gives nothing of the extreme emotional fluctuations in the action or of the nature of Turnage’s brilliant score which with its pulsing motifs and jazzy, saxophone-infused colours takes us from wit and hilarity to sorrow and to savagery. Under Edward Gardner, the orchestra worked wonders. Vocally and dramatically, there were great performances from Allan Clayton as Christian, Marta Fontanels-Simmons as Linda, Natalya Romaniw as Helena, John Tomlinson (yes!) as Grandpa and Gerald Finley as Helge. As Michael, Stéphane Degout was in a class of his own. There were additionally well-observed miniatures by the other 20 or more named singers plus a large chorus and plenty of supernumerary actors. Composer and director have together achieved an amazing feat in marshalling all these forces into an absolutely riveting, sobering, heart-rending and memorable work.

Cecilia